It’s almost 200 years since salt was produced in St Monans but entrepreneur Darren Peattie is on a mission to celebrate the area’s historic links to the industry.

A few hundred yards east of the quaint East Neuk village of St Monans and perched on a raised beach near the shore is a windmill.

It’s one of Fife’s best-known landmarks and is the most tangible reminder of an industry which was once the main source of employment for the whole area – salt production.

Close to the windmill lie the ruins of an old salt pan house – one of nine in operation in the 18th century.

In the 1790s, salt was big news; it was Scotland’s third-largest export after wool and fish.

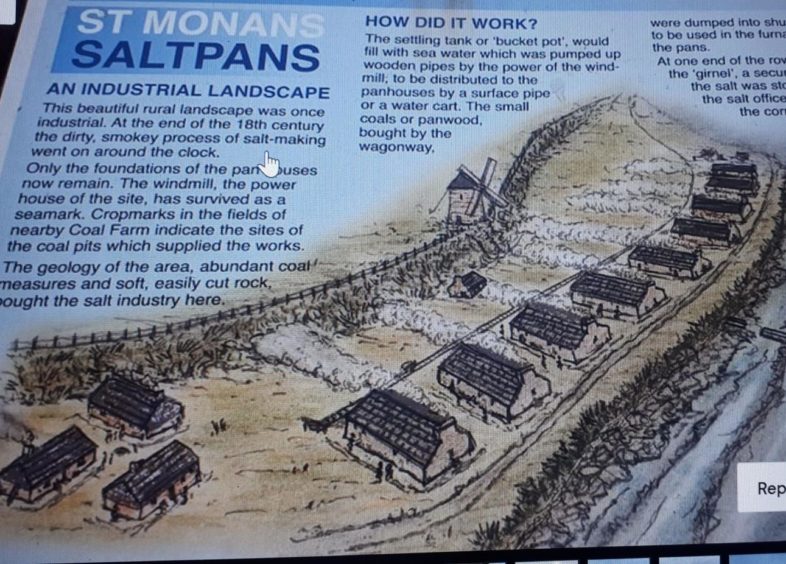

Salt pans were housed in buildings on the beach below the windmill. This provided the power to pump sea water from tidally-fed reservoirs into the pans.

After the water had been boiled, it evaporated, leaving behind the valuable white salt crystals.

The St Monans saltworks operated between 1771 and 1823 and all that’s left of this once thriving industry are ghostly relics of the past.

The surviving windmill stump was restored and reroofed, with new sails attached in the 1990s, and now there are exciting plans to reconstruct one of the old salt pan houses and open it up as a visitor centre.

Local businessman and entrepreneur Darren Peattie is the man at the helm.

Having establishing East Neuk Salt Co last year, Darren is on a mission to resurrect salt harvesting in Fife while preserving the industry’s heritage.

His business, which was launched via a Crowdfunding campaign, will hand-harvest artisan sea salt and Darren says it will be Scotland’s largest and most innovative salt producer.

As well as creating employment in the area, Darren wants to educate people about the story of salt.

Salt heritage

Darren grew up in St Monans and knows Fife like the back of his hand.

He left the area aged 17 due to lack of local opportunities and moved to London to work in finance.

He then moved to the Highlands, where he set up an energy business, and he’s also worked in Dundee and Edinburgh.

Feeling a “spark” to return home, he moved back to the East Neuk last year with wife Mhairi, co-founder of the company, and daughters Esme and Eliza.

“When I moved home in 2019, I found myself walking down past the old salt pans and thought, ‘why’s nobody done anything with salt?’” says Darren.

“I’d come across a salt company in the west coast and thought – ‘we’ve got to bring salt back to Fife’.

“I told my wife we had to set up a salt company and she thought I was bonkers.

“I also felt we needed to celebrate salt, which was once a booming industry here.

“The windmill, the salt pans and the history is all there but nothing had been done with it.”

Salt pan reconstruction

Darren is working with Billy Morris, a member of the village’s community council, on plans to reconstruct salt pan house number seven, turning it into a visitor centre.

“The salt pans are incredibly important for the village but the coastal erosion at the old site is horrendous,” he says.

“If we reconstruct the pan house, and show the working environment of the past, we’re effectively saving the site from ending up in the sea and educating people about the history and heritage of the area and its long links with salt.”

Darren reckons the project will take up to two years to complete and will cost around £300,000.

However, there’s been some confusion locally around what his plans actually are.

“Some folk think I’m planning to bring back the old salt pans and get them in working order but that’s not the case,” he says.

“I had someone stop me in the street and say, ‘you’re going to fill the village with reek’, because that’s what used to happen in the days of salt pan production in the 18th century, with huge furnaces burning coal as part of the process.

“I can assure folk that no smoke will ever leave the chimney! The reconstruction will be just that – it won’t ever been an operational salt pan.”

Darren was also asked why he was “only” rebuilding one salt pan.

“One costs enough!” he laughs. “But if someone wants to offer up the cash, I’m all ears!”

The ultimate aim is to link the past to the present and celebrate St Monans as the true “home of salt”.

“I want people to come into the village, see the old heritage site, develop an understanding of how the salt industry once worked, then move up to our new premises and learn how salt has moved on.

I can assure folk that no smoke will ever leave the chimney!”

Darren Peattie

“The salt pan industry here was short-lived but its impact was huge”.

Darren says local stonemasons are “confident” that work on the pan house can be done.

He hopes it will be ready to open to the public in 2023.

Sir John Anstruther

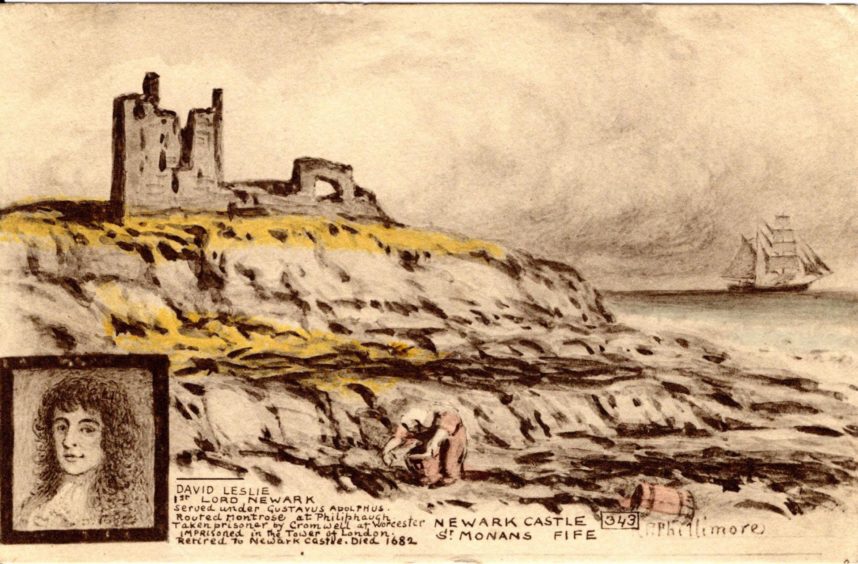

Salt production at St Monans is thanks to Sir John Anstruther, who became the local laird in 1753.

In 1771 he and his business partner Robert Fall established the Newark Coal and Salt Company.

Coal was extracted from a mine immediately to the north of the windmill.

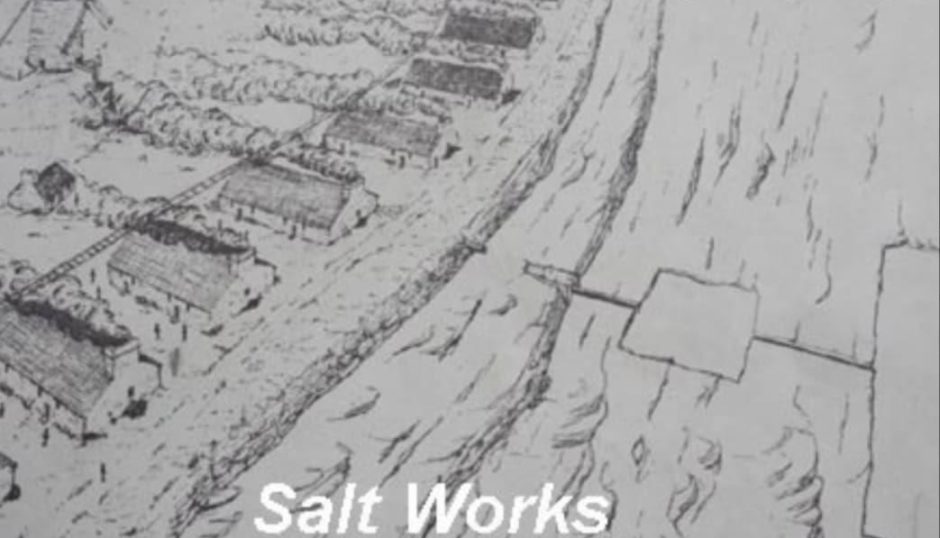

Known as the St Phillips saltworks, the pans were housed in nine buildings on the raised beach below the windmill, whose locations can still be seen today.

Production went on round the clock and at the height of operations the salt pans employed 20 men, while the colliery serving it employed a further 36 men.

The salt pans were linked to the coal mine by a waggonway, which also connected both to Pittenweem harbour.

Major improvements were paid for by Sir Anstruther, on condition that ships carrying his coal and salt had priority over other traffic.

An indication of salt’s value lies in the high levels of tax it attracted; the way it was stored in bonded buildings, and the way it was actively smuggled to avoid duties.

One of the most telling signs of its relative value was that it was deemed acceptable to burn eight tons of coal to produce one ton of salt.

An underground fire in 1794 disrupted the local production of coal, and use of the waggonway to Pittenweem stopped.

Coal continued to be produced to feed the salt pans into the early 1800s, but the entire operation ceased production in 1823.

Workmen unearthed the nine salt pans in the early 1980s and a group of archaeologists returned to excavate them in 1985.

Eight were covered up while one – number seven – was left.

Imagining the salt pans in action

A huge amount of coal was burned to produce salt and that meant the entire area was permeated by choking fumes and smoke.

“It was gritty, heavy, hot, hard labour,” says Darren.

“Back then, they used cast-iron pans and huge furnaces and the place would be filled with steam, fire and smoke – a bit like hell.

“It would’ve been sweaty and arduous and it’s worth noting they use eight tons of coal to produce just one ton of salt.

“They worked through the night, 24/7, to keep the pans boiling and lived down at the pans so there was no escape. Workers woke up to it, went to bed smelling of it, and the waggonway lay above them. It was pretty horrendous.”

Many people who worked in the salt industry remained in the area long after it died out.

“The salt pans contributed to the population of the village,” says Darren.

“It will be nice to give something back – to educate people about the industry and its heritage and, in tandem, to produce Scotland’s nicest, highest-grade sea salt in a sustainable, environmentally-friendly way.”

Scottish salt

Salt pans were in use in the Fife village of Culross from as early as the 1500s.

Before long, there were few places along the banks of the River Forth where salt was not being extracted to serve the needs of industries like glass and pottery manufacture.

Salt was also increasingly in demand as a food and fish preservative, allowing the growing catches of Scotland’s fishing ports to be exported.

The Scottish salt industry reached its peak in the early 1800s, when it flooded the English market, due to a more lenient tax north of the border.

However, with the repeal of salt duty in 1823 and the import of cheap rock salt from abroad the salt industry collapsed.

The legacy of salt extraction remains mostly in a series of place-names alongside the River Forth involving “pan” or “pans”.

The most well known of these is Prestonpans, where industrial salt extraction continued until 1959.

Salt harvesting in 2020

The small batch salt Darren has prepared for local firms and chefs is not for general sale yet, but he says the feedback from industry professionals has been phenomenal.

He has secured premises in the heart of St Monans.

The former Bass Rock Oil Company yard was recently bought by local developer Alan Waugh and East Neuk Salt Co will form part of this new investment in the village.

Darren is conscious of supporting the local environment and area and will run his operation on a zero-waste ethos.

“We take 2,500 litres of water per day from the sea – we’re allowed to take 10,000 cubic metres,” he explains.

“Sea water is 3% salinity. We need to take that water and put it under vacuum evaporation which is pressure and heat to create a brine. The brine is basically concentrated sea water.

“It then gets put into crystalliser trays and over several days, turns into beautiful salt flakes. It goes on to be dried, gets packaged and is then off to retail.

“St Andrews University tested the water from the East Neuk for us and my word, I can see why it was called the white gold in the past. It’s absolutely incredible.”

All salt harvesting equipment is currently being shipped over from the Netherlands and it should arrive in a fortnight.

“All branding and packaging, with an emphasis on being environmentally-friendly, is complete,” says Darren.

“We’re currently engaged with suppliers locally, nationally and internationally.

“We’re working on building our employment team with locals based around marketing, admin and of course salt harvesting.”