The closure of Camperdown Works 40 years was the death knell for Dundee’s ‘Juteopolis’ empire.

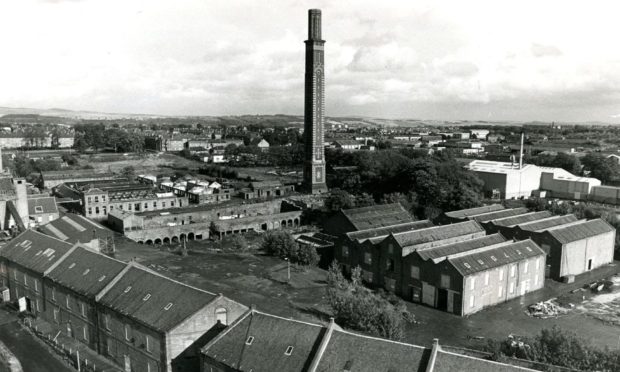

For 130 years the Camperdown complex, at one time sprawling over more than 25 acres, was the industrial giant of the suburb.

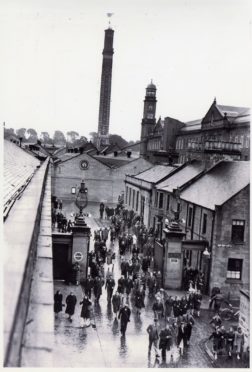

Countless thousands of Lochee folk spun there, sons and daughters following parents, generation after generation.

When the jute trade was busy, Lochee prospered.

Irish counties

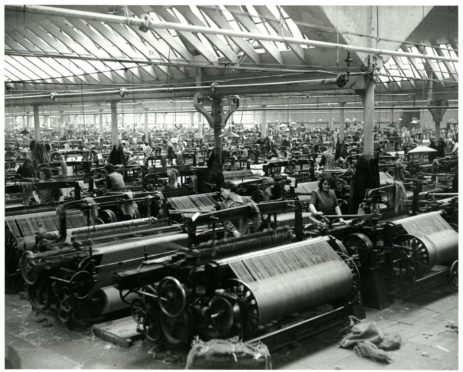

In its heyday the city was the world centre for the manufacture of the fabric, with around 50,000 people dependant on the industry for their livelihoods.

The impact of the jute industry ultimately attracted more people to Lochee.

Irish workers started to arrive to join the endless rows of women, men and children who made the bobbins fly and the mills bustle.

They came mainly from the Irish counties where linen and yarn were produced such as Donegal, Londonderry, Monaghan, Sligo and Tyrone.

By 1900, Camperdown Works employed over 5,000 people and was one of Britain’s greatest industrial complexes.

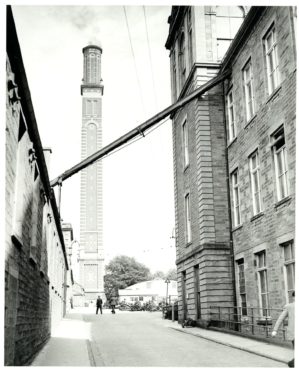

The 282-foot Cox’s Stack was the landmark for what became the largest jute works in the world.

Underground tunnels fed it from 58 furnaces.

The Cox family built it to ensure smoke from the furnaces was carried well above the nearby workers’ houses.

The red and white brick chimney was built in 1866 and reputedly contained a million bricks.

Camperdown was so big it had its own branch line and railway station.

The industry was hit by a series of booms and slumps in the 19th century, before falling into decline in the 20th century.

Camperdown weathered the storms

In 1920, Cox Brothers was one of several Dundee firms which came together to form Jute Industries (which later became Sidlaw Industries), under the chairmanship of James Ernest Cox, with Camperdown remaining one of its key works.

By 1950, there were only 39 jute firms left out of a total of 150 at the industry’s peak, with polypropylene being widely used as the backing for carpets at the expense of jute.

But Camperdown weathered all the storms until markets slumped to an all-time low.

The announcement by Sidlaw Industries was made in January 1981 that Camperdown Works would be closing.

The 340 jobs which went would bring to close on 2,000 the redundancy total for jute, propylene and carpets in Dundee since the start of the 1980s.

The jute industry of Tayside shrunk to some seven firms with probably less than 3,000 of a workforce.

Sidlaw Industries were left after the Camperdown closure with 650 textile employees and only two jute mills at Manhattan in Dundee and Selbie in Gourdon.

The directors were hopeful that the closure would ensure the remainder of their jute operations would become viable after they had been running at a heavy loss.

There was an atmosphere of gloom and despondency in Lochee although workers admitted the closure was inevitable.

Blow to the city

Local historian Dr Kenneth Baxter from the University of Dundee said: “Although by 1981 its workforce was a fraction of what it had been at the start of the 20th century, Camperdown Works was still employing a workforce of 340 people when it was announced that Sidlaw Industries were ending their textile operations at the site.

“Aside from the obvious financial implications for those who would lose their jobs and local businesses which had benefited from the millworkers custom the closure was undoubtedly of huge symbolic importance for Lochee and for Dundee as a whole.

“Camperdown Works was inextricably linked to the growth and history of Lochee for over a century and a quarter, so its closure was always going to be felt hard by its inhabitants.

“Although it was not quite the end of the jute industry in Dundee, Camperdown Works’ closure cannot be seen as anything other than a blow to the city.

“Camperdown Works, and its famed Cox’s Stack, can be seen as the ultimate physical symbols of Victorian Dundee’s industrial might.

“The end of this iconic works showed beyond question that the era of Dundee as a great centre of the textile industry was well and truly over.

“While a significant portion of the site would eventually be redeveloped, for some time after the closure the derelict buildings and others remains of industrial activity on the site served as a rather stark reminder of the rise and fall of Juteopolis.”

Following closure of the works in 1981, some parts of the complex were sold for demolition in 1985.

Christabel

The BBC used the site in 1988 to double for a bombed-out wartime Berlin in its mini-series Christabel where Dundee High School pupils were used to portray urchins playing among the rubble.

Much of the industrial heritage made way for the Stack Leisure Park which opened in 1993.

Cox’s Stack was retained as a landmark feature linking the new commercial area with the housing.

The end finally came when the freighter Banglar Urmi arrived in Dundee in October 1998 to signal the end of a glorious era in the city’s history.

The 310 tonnes of raw jute on board represented the last consignment to be spun at the last mill in Dundee, the Tay Spinners premises in Arbroath Road.

Once the consignment was spun into yarn for carpet backing, all that was left of the industry was a heritage museum and bitter-sweet memories.

“At its peak Camperdown Works employed 5,000 hands,” said historian Dr Norman Watson.

“It made its own machinery, had its own railway stop, fire station and school.

“In its time it was the biggest and grandest jute mill in the world.

“In other words, Lochee put all its employment eggs in one basket.

“Its strength in Victorian times became its undoing in the 20th century.

“There was little alternative work and in some ways the suburb has never recovered from jute’s gradual decline.

“When Cox’s whistle blew and the Camperdown gates swung open, a sea of cloth-capped, shawl-clad workers spilled on to Lochee High Street.

“Pictures of closing time are reminiscent of the full-time exodus at Tannadice or Dens.

“Now Lochee’s streets are too often quiet.”

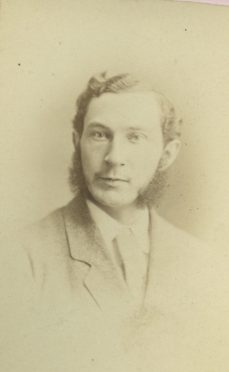

Edward Cox was hugely influential in all areas of city life

Dundee bred Edward Cox inherited Cox Brothers, the family firm, after his father died in 1885.

He helped turn the company into one of the world’s best known jute manufacturers and the largest ever industrial concern in Dundee.

His contemporaries described him as a man of great business ability.

Cox was hugely influential in all areas of city life and from a young age he was involved in philanthropic and religious work.

He was president of the Dundee Chamber of Commerce and also a governor of University College Dundee (now University of Dundee).

Gift to the city

Cox’s power stretched across Scotland and the UK in his post as director and deputy chairman of the Caledonian Railway Company.

In addition to taking a keen interest in the university, Cox purchased the Alexander C Lamb collection of old Dundee literature and pictures and presented it to Dundee Library as a gift to the city.

Cox stepped in when the collection was on the point of being dispersed to ensure it survived in the city intact.

He died from pneumonia aged 64 in March 1913 at his Cardean estate in Meigle, Perthshire.

Cox died with an estate worth over £700,000, which would be about £62 million after inflation today.