An electricity revolution, designed to power some of the remotest communities in Scotland, sparked into action 70 years ago. Gayle Ritchie looks at how Pitlochry Dam transformed life in Highland Perthshire forever.

Homes in Highland Perthshire in the 1940s were far from luxurious.

Only one in six farms and one in 200 crofts had electricity.

But when visionary politician Tom Johnston realised the untapped potential of hydro power in Scotland, things looked set to change.

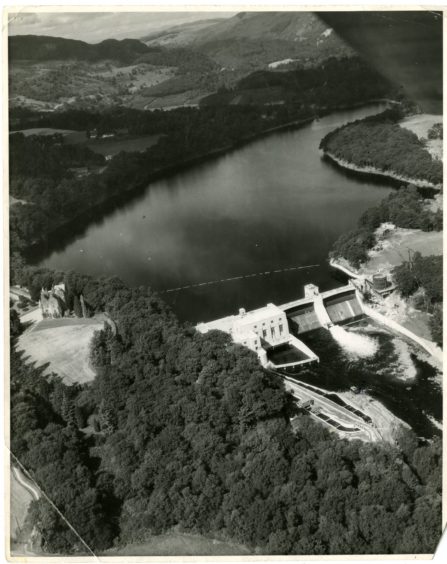

Plans to create a dam across the River Tummel in Pitlochry promised to turn natural energy into affordable electricity, transforming the way people lived and worked.

However not everyone was jumping for joy at the prospect.

Before construction got underway in 1947, many people feared the scheme would desecrate the glorious Perthshire landscape.

A petition against the project encouraged people to write to their local MPs and organise protests.

It read: “No-one acquainted with the scenic beauty of the Pitlochry district can fail to feel dismay at the prospect of that beautiful and historic piece of country being desecrated by the proposed scheme.

“River beds will be dried up; the Falls of Bruar will become a mere trickle; Clunie Bridge, the recreation park and many homes and farms will be submerged; and the Queen’s View and many other delightful scenes will be altered out of all recognition.

“There will, too, be great monetary loss to the township of Pitlochry, where many a weary city dweller has spent a pleasant and restful holiday.”

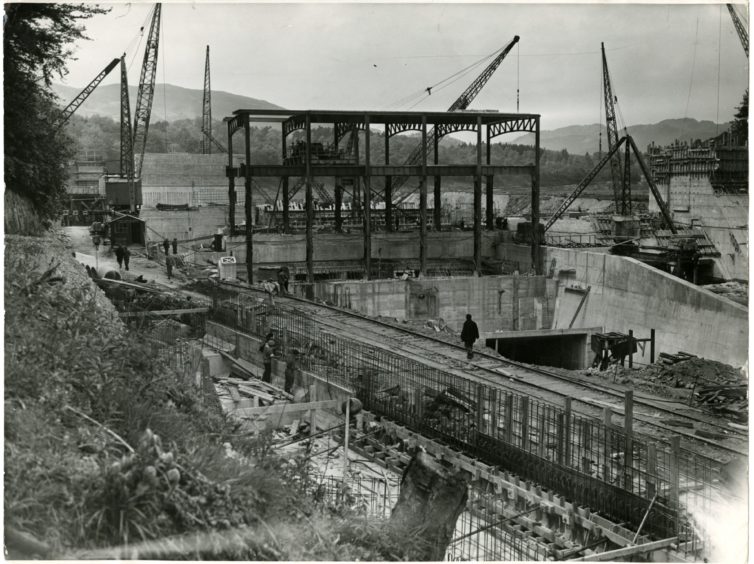

Any protests fell on deaf ears and construction on the new hydro station began in 1947, with the Countess of Airlie laying the first block of stone on April 26 that year.

Pitlochry Dam took four years to construct and was hampered by winter flooding.

The project was further delayed when construction workers went on strike over poor quality food they were receiving.

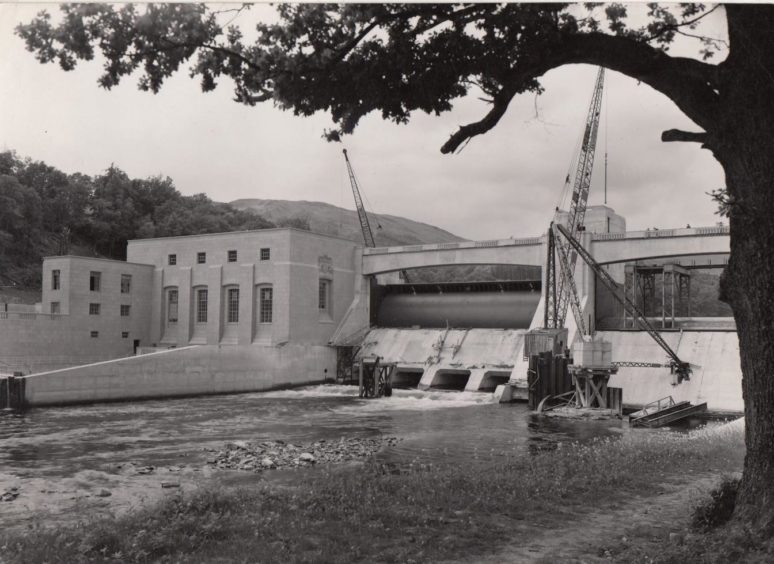

Construction finished on January 10 1951 and an opening ceremony was planned for June of that year.

Tragically, the head engineer of the Hydro Board, Sir Edward MacColl, died just before the opening and a much more subdued ceremony was held in 1952 where a plaque in his honour was unveiled at the power station.

Former archivist for SSE Alasdair Bachell says the scheme was quite “controversial”.

“Not only did people fear it would be damaging to local tourism but it was also strongly believed that the advent of nuclear energy would provide clean, free energy for all in the future,” he says.

“There was also concern that the natural landscape would be irreversibly changed and beauty spots such as waterfalls would dry up.

“These concerns were not unfounded, and many pointed to a similar project in the USA by the Tennessee Valley Authority which had displaced hundreds from their homes and drastically altered the landscape.”

The doom-filled prophesies didn’t materialise, thankfully.

And as the project took shape, local people began to warm to the idea.

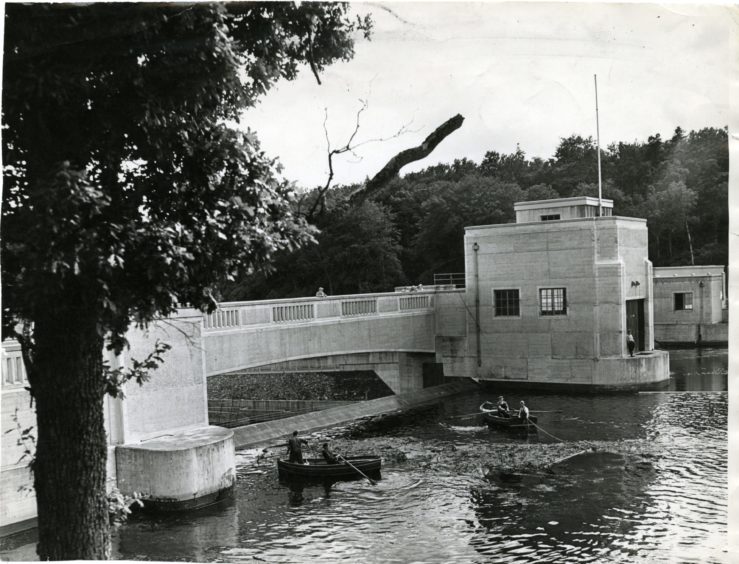

Architects designed the dam to look aesthetically pleasing, with clean lines and no overhead power cables.

It was light grey in colour – quite stark in the landscape but equally impressive.

And because the dam would’ve been an impassable obstacle for economically-important migrating salmon, the now iconic fish ladder was constructed, allowing the salmon to swim from the Tummel into the loch.

For public benefit, they added a walkway across the dam and a viewing chamber in the fish ladder.

“With the creation of new lochs, roads and tunnels, the very landscape of Scotland was changed in a profound way,” says Alasdair.

Perthshire continues to prosper, its beauty untarnished by the dam and power station, and some argue it’s been enhanced with the creation of Loch Faskally.

The man-made reservoir, popular with anglers, kayakers, canoeists, paddleboarders and walkers, and often used to host the award-winning Enchanted Forest spectacle, was built to stabilise river flows below the dam at Pitlochry.

And, if it wasn’t for Covid-19, tourists would be flocking to the dam, to the power station’s new visitor centre, and to the loch, in droves.

Engineering marvel

Pitlochry Dam is a marvel of mid-20th century engineering.

It is part of the Tummel-Garry scheme – a system of dams and power stations incorporating two older power stations (Rannoch and Tummel) which were built in the 1930s by the Grampian Electricity Supply Company.

Men from across Europe were employed to build the dams and at its peak, there were around 12,000 working on the schemes including prisoners of war.

Many lived in camps and some in cottages or wooden huts.

“Conditions working at the dam would have been quite dangerous, with few, if any, health and safety regulations,” says Alasdair.

“Photos from the time show very few workers wearing hard hats which would be completely unthinkable now.”

The dam’s new visitor centre, opened in January 2017, boasts interviews with former engineers and workers which highlight such harsh working conditions.

They include the memories of original Donegal Tunnel Tigers John ‘Gonna’ O’Donnel.

He recalls: “My first role was a ‘spanner’ man. It was a tough job which involved holding the drill machine for the four men working above me.

“Closing my eyes I can still feel the tumbling rocks coming down on my bare knuckles and how the constant drilling affected my hearing so that my ears rang constantly for that first fortnight in Perthshire.

“It was horrendous. But it was work, and for that I was very grateful.”

As John’s expertise expanded, he spent most of his tunnelling career managing explosives.

“If I sniff the air I swear I can still conjure up the smell of the thick, black, choking, dust and smoke which followed each enormous blast,” he says.

“Boy, did the ‘geli-reek’ give us a sore head – or maybe it was because we had to hold our helmets on so tightly to stop them being blown off!”

If I sniff the air I swear I can still conjure up the smell of the thick, black, choking, dust and smoke which followed each enormous blast.”

John ‘Gonna’ O’Donnel

Meanwhile fellow Tunnel Tiger Denis (Dinny) O’Donnell recalls: “A fall of rock came down on top of me and I was knocked unconscious. I was taken to a hospital in Glasgow. My leg was damaged.

“I got stitched up anyway and came back to the camp again. I was there maybe for two weeks and I went back to work again then. And no great harm done.

“The fall that came down on me that day, it could have killed me. But I was lucky it just got my leg.”

In terms of deaths during construction of the Tummel-Garry scheme, there’s no concrete number.

“The short answer is nobody knows for sure, though at least five died building Clunie tunnel and their names are written on the memorial arch by Clunie power station,” says Alasdair, also a PhD researcher at the University of the Highlands and Islands.

“The men who died were working with explosives during a storm and lightning struck the facing where the charges had been set, causing them to prematurely detonate.

“Since the Health and Safety Executive didn’t exist, deaths and accidents were not consistently recorded.

“Some schemes have memorials to those who died (such as Sloy where at least 20 men died), but most do not to my knowledge.

“There are plenty of anecdotes about the deaths on the schemes, but no concrete numbers unfortunately.”

Changes

Pitlochry power station was refurbished in the 1990s.

But ultimately, the station and dam are very much the same as when they were first built, albeit with some more modern control hardware on the inside.

“The concrete has aged, as concrete does, turning darker and settling into the landscape more and the characteristic drum gates have been painted a few different shades of blue or green,” says Alasdair.

“The biggest change is likely the visitor centre, which was once in the station itself, now where the archive is.

“It’s worth noting that in some ways the station can’t change too much as it is a grade A listed building.”

Alasdair believes the contribution Pitlochry power station and dam makes to Scotland’s renewable energy is incredibly important.

“For Scotland as a whole this is its most valuable contribution especially considering our extensive efforts to reduce carbon emissions,” he says.

“Its contribution to Pitlochry’s tourism is not to be understated though.

“It is a unique hydro station in just how easily accessible it is to the public unlike most dams and stations which are quite remote and generally not viewable by the public.

“This makes it a valuable historic and educational resource for Pitlochry.”

In October 1952, Tom Johnston, chairman of the North of Scotland Hydro-Electric Board from 1946 to 1959, said: “We must never forget that the North of Scotland Hydro-Electric Board is more than a producer and distributor of electricity; it is more than a coal saver; it is an agency, as will be demonstrated in the years to come, a powerful agency for the economic and social rehabilitation of vast areas and scattered populations north of the Forth.”

The future?

SSE Heritage Development Officer Holly Cammidge says the number of people who passed over the dam annually, pre-2017, was around 500,000.

“The number of visitors to Pitlochry Dam Visitor Centre since it opened in January 2017 has been around 100,000 per year – until the Covid restrictions kicked in in March 2020,” she says.

“Every year, the two turbines that run at Pitlochry power station combined meet the energy needs for some 15,000 homes and are helping the country to meet its commitment to provide more energy from renewable sources.”

The dam walkway is currently closed to the public to protect staff carrying out maintenance.

The visitor centre is also closed, in line with government guidance, until further notice.

Hopes are high that the 70th anniversary can be marked in summer with a celebratory exhibition at the visitor centre.

“There is lots more research still to be done to create a complete look back at the history of the dam and power station which will include lots of visuals from the archive,” adds Holly.

For more details, see pitlochrydam.com