The son of Fife war hero John Robert Mills has retraced his father’s footsteps from a farm near Ceres to the “thousand-bomber raids” of Germany in 1942.

If he had lived 10 years longer, February 13 2021 would have been John Robert Mills’s 100th birthday.

He passed away aged 90, but his chances of living so long must have seemed unlikely when he was under fire during the Second World War.

John’s son Iain has used his time during lockdown to research his father’s life and military service, retracing his footsteps from a farm in the Great Depression, to years spent in Canada, to the “thousand-bomber raids” in Germany during the summer of 1942.

“My father was a quiet hero, and did not accept that he was any different from the thousands of other men from Scotland who served during the Second World War,” says Iain, 70, a retired teacher and lecturer.

John was born in 1921 at Rosemount of Callange, a farm just over a mile east of Ceres in Fife.

His parents were John Mills and Alice Morrow and he had two younger sisters.

My father was a quiet hero, and did not accept that he was any different from the thousands of other men from Scotland who served during the Second World War.”

Iain Mills

Their house was basic – water needed to be carried from a well 50 yards away.

“He claimed that one of his abiding memories of his childhood was being cold: he often went into the blacksmiths for a heat on his way home from primary school,” says Iain.

“He had just left Bell Baxter High School in Cupar when war broke out, and he volunteered to help deal with evacuees, mainly from Edinburgh.

“When they arrived at Cupar Station they had to be united with the families they would be staying with.

“He described them as being somewhat bemused by their new, more rural surroundings, and it wasn’t long before a number of them started drifting back to Edinburgh.

“Around this time, John’s own family moved from Callange to Letham, near Cupar, where they stayed in the first house in The Row.

Although John enlisted in the RAF at the start of the war, he wasn’t called into action until early 1942. By then he had completed two years of a teacher-training course in Dundee.

For his first RAF posting, he had to make the hazardous crossing of the Atlantic by ship and continue over the Canadian Prairies by train.

He arrived at an airfield near Calgary, Alberta, where he began his pilot training at the tender age of 21.

“Not all pilots survived the training course, but my father’s only injury was frostbite on one ear from the bitter Canadian winter,” says Iain.

“On completion of training, he returned to Britain to report to a Bomber Squadron for active duty.

“In those days, the casualty rate for bomber crews was very high and their life expectancy alarmingly short.”

John was posted to Lincolnshire, from where many of the air raids to the continent were launched.

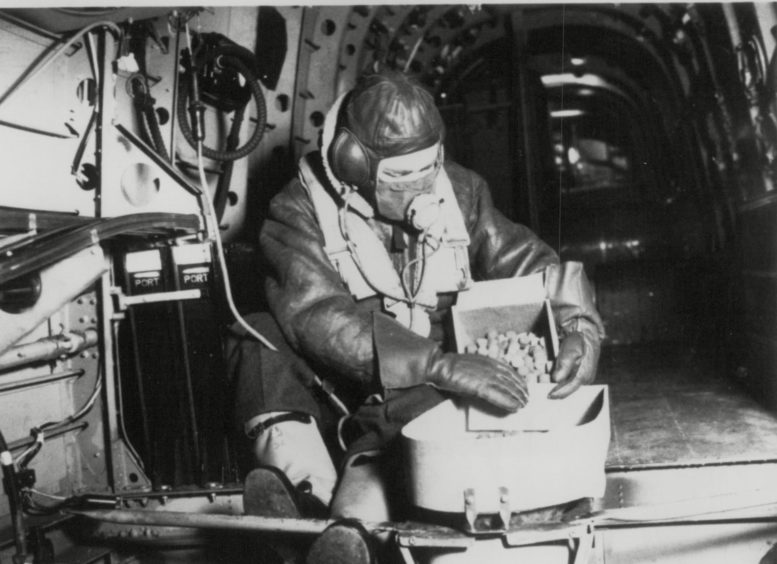

He flew various types of bomber, including Wellingtons, but most of the planes he piloted were Lancasters or Avro-Lancasters.

These were often slower than the enemy aircraft that would be waiting for them, and many aircrews would not return.

He took part in a number of raids on German-occupied France, and, later, over Germany itself.

“He was one of the pilots in the ‘thousand-bomber raids’, which were perhaps good for British and American morale but came with a high mortality rate,” says Iain.

“Every time he returned safely to base, he was aware of friends who hadn’t made it back.

“Although he rarely spoke about the war, he once described flying into German flak over the Ruhr and feeling it was very unlikely that he would survive that mission.

“That he did was partly down to his skill as a pilot, but also, he claimed, sheer luck.

“He felt that the bombers were often ‘like sitting ducks’.”

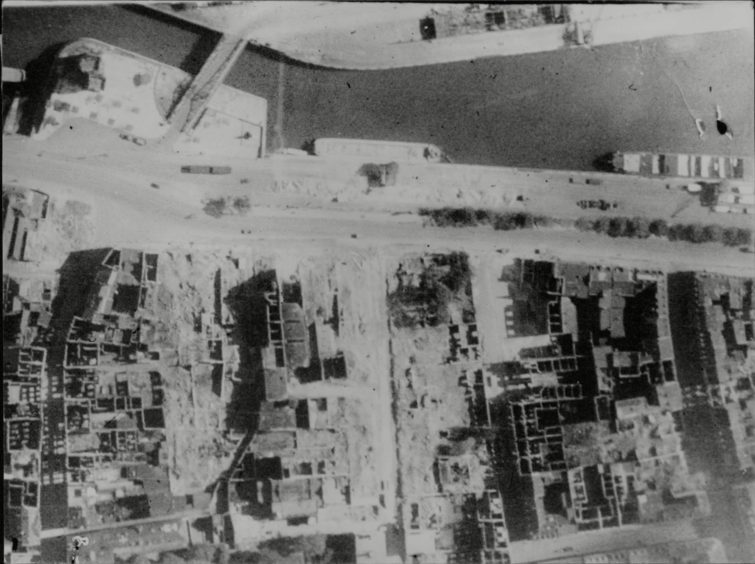

The “thousand-bomber raids” were attacks on Germany by massed allied aircraft, beginning in 1942.

They were largely for propaganda purposes – a show of force.

“Other mass raids also took place,” says Iain. “However, the German cities – such as Dresden – were fiercely defended by German anti-aircraft guns, and many RAF bombers were struck with shrapnel and did not make it back home. ”

Towards the end of the war, John was transferred to RAF Wigtown in Galloway and his role changed from bombing raids to troop transport, including flights home from the middle east.

It was at Wigtown that he met his wife, Irene Moore from Gourock who was a member of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF).

They married on August 6 1945 – the day the nuclear bomb was dropped on Hiroshima.

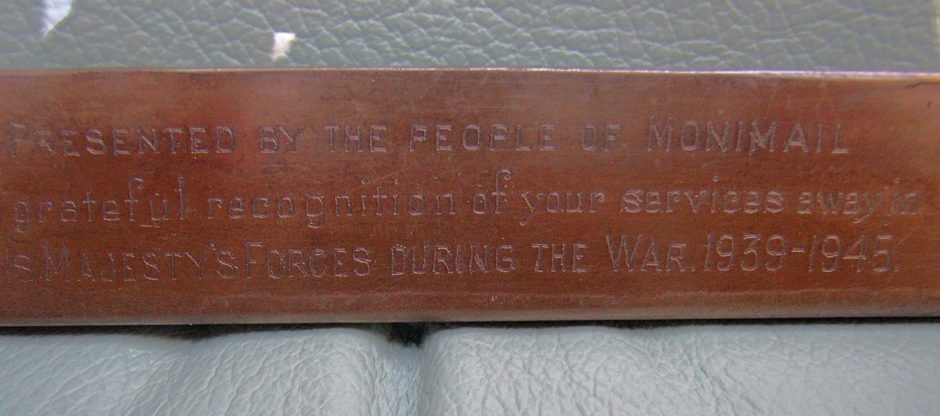

John was presented with an inscribed photo frame by the parish within which Letham lies – Monimail Parish – for his role in the war.

Once he was demobbed, he finished his teacher training and went on to teach in secondary schools across Fife and Renfrewshire.

Later, John and Irene had two children, Iain and Ailean and went on to become grandparents to five children.

But John, who spent his last 26 years in the west coast town of Largs, rarely mentioned the war during his later years.

“It’s hard to imagine what my dad went through on bombing missions,” says Iain, also of Largs.

“He must have displayed enormous courage under extreme and terrifying conditions.

“It wasn’t just his personal survival that concerned him. He felt a responsibility for getting his crew home safely as well. He was always a very caring person.

“However, he had serious misgivings about the bombing of civilian targets in Germany, and never gloried in what he had achieved.

“He was only 21 when he started his pilot training, and 22 when he flew on missions over Europe.

“He must have been incredibly strong mentally to keep a clear head in those circumstances.”

It wasn’t just his personal survival that concerned him. He felt a responsibility for getting his crew home safely as well.”

Iain Mills

John died in July 2011 and his family miss him hugely.

“He was such a kind and helpful man, and it’s sad that we can’t all get together with him on what would have been his hundredth,” laments Iain.

Thousand-bomber raids

The term “thousand-bomber raid” was used to describe three night bombing raids by the RAF against German cities in the summer of 1942 during the Second World War.

Sir Arthur Harris, nicknamed Bomber Harris, was the commander-in-chief of the RAF’s Bomber Command.

In May 1942 Harris was directed to launch raids on industrial centres while targeting “the morale of the enemy civilian population”.

The target was the industrial city of Cologne; the tactic was to overwhelm city defences by sending 1,000 bombers overhead in the space of 90 minutes.

On the night of May 30, 890 bombers reached Cologne, causing massive damage.

According to German figures, 469 people were killed and 45,000 made homeless.

Only 41 aircraft were lost.

Harris followed through with a second raid two nights later, fielding 956 bombers against the industrial town of Essen.

Due to the target-acquisition problems endemic to the Ruhr valley, relatively little damage was done.

A third raid, in which 960 bombers targeted the coastal town of Bremen, took place on June 25.

Damage was more extensive than in Essen, although it fell far below the levels of the Cologne raid.

While some military installations and several shipyards were hit, most of the damage was to residential areas.

Harris was knighted shortly before the Bremen raid.