Could a brooch provide the final chapter in the story of a Fife doctor who perished in the worst disaster in the history of British polar exploration?

The brooch contains the hair strands of Dr Harry Goodsir who witnessed unspeakable horrors and suffering on the 1845 Franklin expedition which ended in cannibalism.

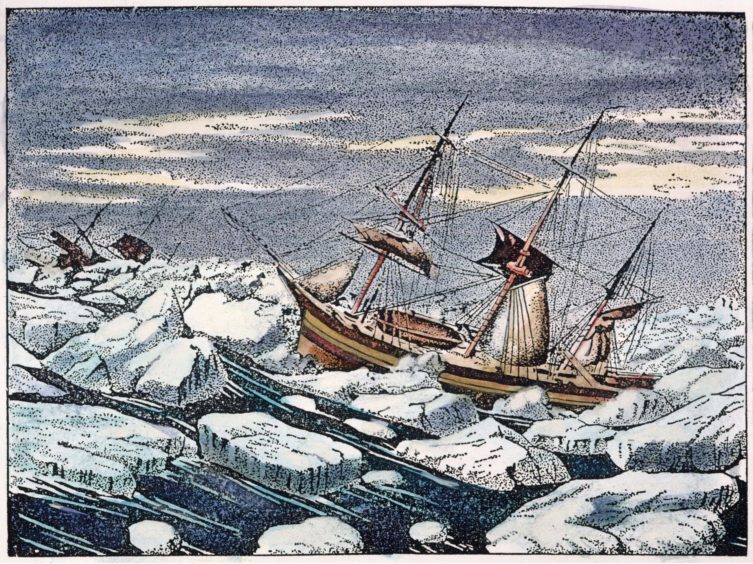

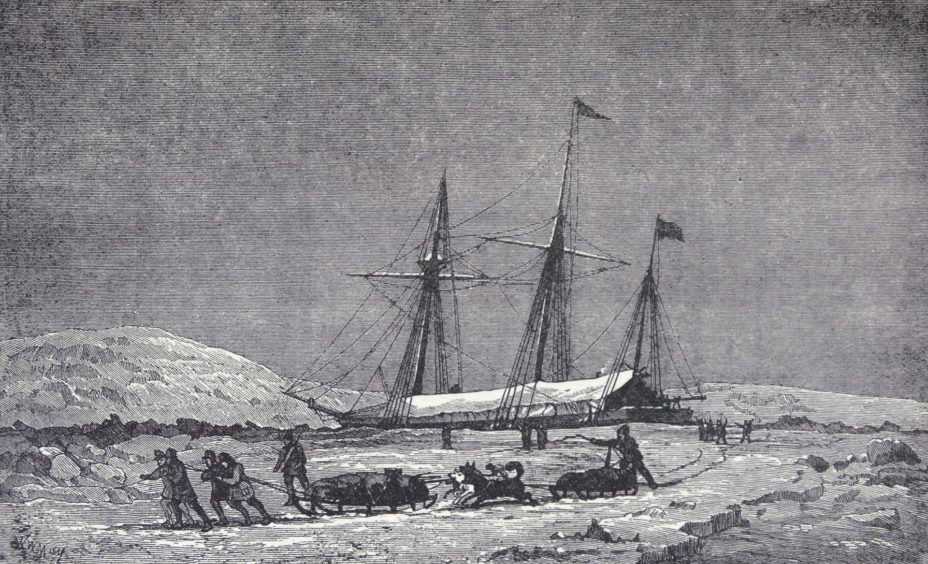

Arctic veteran Sir John Franklin departed Britain in command of two ships, the HMS Terror and HMS Erebus, to seek the fabled Northwest Passage.

Terror and Erebus were abandoned in heavy sea ice in 1848 and the men sought a route to safety across the frozen Arctic on foot.

Every one of them died in the endeavour.

Partial skeleton of an officer was discovered

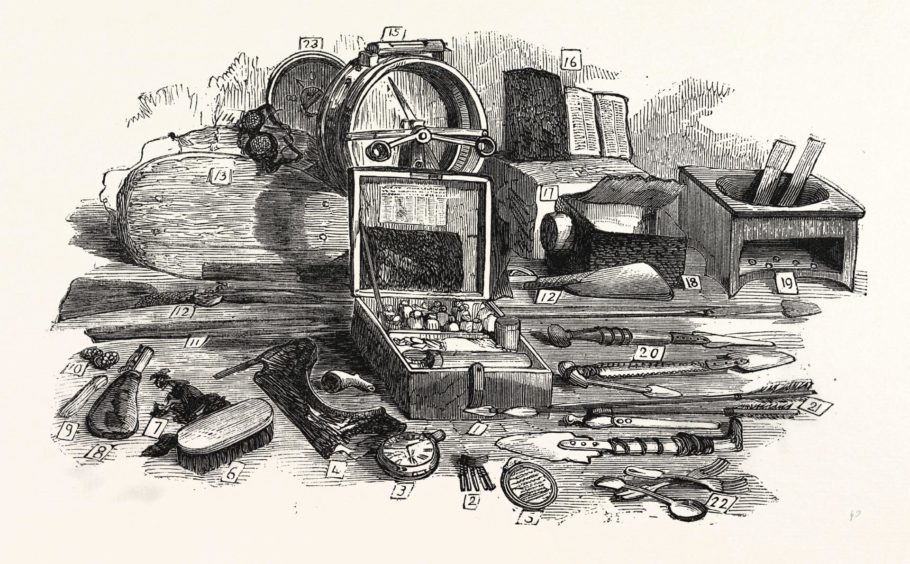

Twenty-five years later, an Inuit guide led explorers to a spot on King William Island where a shallow grave contained the partial skeleton of an officer.

The remains were sent home to the UK, where the renowned biologist Thomas Henry Huxley wrongly identified them as Lieutenant Henry Le Vesconte.

A new forensic analysis of the skeleton in 2009 – which was buried in the Franklin Memorial in Greenwich – found a likely match in Dr Goodsir.

Michael Tracy, of Chicago, Illinois, one of Dr Goodsir’s closest living relations, has spent over a decade researching the distant medical branch of the family.

The brooch was discovered after documents which are held in the Goodsir archive at Edinburgh University suggested it was held by relatives in Alberta, Canada.

The current owner is Court Mackid who agreed to jointly donate it with Michael to the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh.

That was where Dr Goodsir once served as conservator, and where he and two other family members received their professional licences.

Further DNA advances could solve the mystery

The museum will take ownership following the easing of lockdown restrictions with a stipulation it would allow for future testing of the hair samples.

Michael said: “One thought, of course, was to have it tested for DNA, but the risk was too great because of the difficulty of analysing rootless hairs.

“There is only one lab in the world that can currently conduct these tests but due to the backlog it would have taken years to even get the hair strands tested.

“Who is to say what another decade will produce in the continual march of science?

“This brooch tells a story of these individuals and is beyond doubt unique, however, its final story has yet to be told.

“It is my profound hope and wish that the brooch’s content, combined with further advances in DNA technology, will conclusively identify the currently unknown remains interred beneath the Franklin Monument in Greenwich as those of Harry Goodsir.

“No words of mine can adequately express what this would mean to me.”

Dr Russell Porter, author of Finding Franklin: The Untold Story of a 165-Year Search, said the brooch “may be one of the most extraordinary relics of the Franklin expedition that’s never before been seen”.

Michael and Dr Potter are also working with fellow author Tom Gross to write a concise biography on Dr Goodsir and the once illustrious medical family from Fife.

Life and times of a famous medical family

Born in 1819, Harry Goodsir grew up in the East Neuk of Fife at Anstruther Easter, Backdykes, The Hermitage.

He was raised by his father John and mother Elizabeth, along with his five siblings John, Joseph, Jane, Archie, and Robert.

A sixth, Agnes, died in infancy.

Father John, as the local doctor, was well known to both local people and connected with the surrounding estate gentry.

As Harry was growing up, the shores of the Firth of Forth played an important role not only in his upbringing but also in his career.

Walking along its shoreline with his older brother, John, he would collect the abundant marine life in their path, cementing an interest in marine biology for the rest of his life.

His parents played significant roles, with his father encouraging his studies at school while his mother taught him to draw exceptionally well.

Her loss, when he was 21, would have a profound impact on him.

Central to Harry’s career path was the example of his older brother, John, who shaped his medical studies at the University of Edinburgh.

John Goodsir, the great anatomist and pioneer of the study of cell biology, was perhaps the most accomplished anatomist and the most successful teacher of his time.

Harry followed in the footsteps of his successful brother as he succeeded him in 1843 as the Conservator of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh Museum.

It was John, who was one of the earliest to bring the compound microscope to Edinburgh, who offered to similarly equip his brother, Harry, if he sent him £10 to cover the cost of the instrument.

Harry was awarded his Licentiate in Surgery in 1840 and immediately set out to work by assisting Dr John Reid in the Royal Infirmary in Edinburgh, as well as supporting his ailing father’s East Neuk medical practice.

Harry was also a rising pathologist and morphologist in his own right and great things were expected from him.

Harry Goodsir was offered Arctic post by Franklin

Fate intervened for the young doctor and naturalist when he was offered the post of Acting Assistant Surgeon and Naturalist on HMS Erebus, a polar expedition that aimed to chart the elusive maze of Canada’s Northwest Passage and was the only member of the crew not from a naval background.

Michael said: “Harry was thrilled, because now he could immerse himself in marine biology and when the Erebus’s dredges were deployed and brought up various creatures of the deep he was exuberant.

“One has only to read the surviving letters he wrote home to clearly capture an accurate picture of his energetic and enthusiastic sense of scientific enquiry.

“His considerable expertise powers in specimen illustration was demonstrated daily on a table provided for him by Sir John Franklin in his quarters.

“Harry gleamed with joy as one of the first members of the crew to climb on his first iceberg.

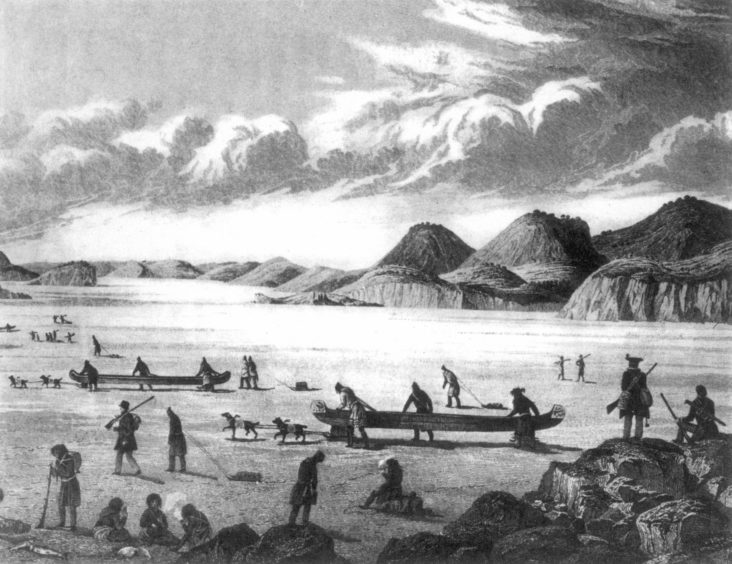

“As the ship’s librarian, Harry not only compiled an Inuit vocabulary dictionary, but also closely observed the Inuit peoples’ anthropological characteristics, even to extent of wanting to make casts of their heads and faces.

“When Erebus and Terror were encased in the icy grip of the waters off King William Island and the long encampment began, one can only imagine the utter fear and panic that consumed the minds of the officers and crew.

“Cut-off from external communication, hope of an immediate search and rescue was abandoned.

“Each member of the crew began their slow, painful, march in extreme temperatures, moving ever so slowly in death’s icy grip.

“During these long days and months, death was probably welcomed.

“As for Harry, he may have been one of the last to perish near the Peffer River in the southernmost part of King William Island.

“Given the values with which he was imbued, one feels sure that Acting Assistant Surgeon Harry Goodsir demonstrated a doctor’s deep compassion to relieve the suffering of the officers and crew in such desperate conditions that turned out to be their shared ‘death march’.

“In the face of the extreme weather and with dwindling food supplies, Harry watched as, one by one, as the crew succumbed to a catalogue of illnesses: starvation; tuberculosis; scurvy; pure madness, possibly brought on by lead poisoning; and a resort to cannibalism in an ultimate effort to stay alive.

“Throughout, Harry administered medical treatment, comforted the disenchanted, and reassured the dying.

“No words can adequately describe the absolute bleakness, despair, and pure horror that must have passed through the minds of those gallant men of long ago as they walked to their own personal doom.

“As we all emerge from the long lockdown winter of 2021, imagine the nightmare of trudging through the snowy wastes of northern Canada with almost no food and little hope of survival.

“Rescue is not at the end of a mobile phone but rather a year away.

“In conclusion, it is worth remembering that the tragedy of this once prestigious Royal Navy expedition resulted in the greatest loss of life in the history of polar exploration.

“The immensity of the catastrophe, and subsequent lack of information as to the whereabouts of the dead, had far-reaching consequences on their families.”

Tragedy in the Arctic was shared by 128 families

Michael said the Goodsir family were grief-stricken and never fully recovered.

The tragedy of the Goodsir family was shared equally by the 128 families of the lost crews of the Erebus and Terror, all now shrouded in the snowy wastes of Canada.

“Harry’s life story demonstrates how a local Fife lad with an instinctive quest for natural history could; through his industrious application at primary school in Anstruther Easter, possibly attending Madras College in St Andrews, and the University of Edinburgh, become a naval surgeon and de-facto naturalist for the foremost expedition of his time,” said Michael.

“His self-belief and perseverance in the pursuance of scientific knowledge is an inspiration to us today.

“It is in this spirit that a commemorative plaque was laid near the spot where he perished on King William Island.”

Louise Wilkie, Curator, Surgeons’ Hall Museums, Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, said: “We are very happy to accept the Goodsir family brooch, kindly donated to the museum by Mr Court Mackid and Michael Tracy.

“Both Harry Goodsir and John Goodsir were conservators to the museum, so it seems quite fitting that the brooch will join the collection that they once worked hard to build and preserve.”

Harry Goodsir is brought to life by Paul Ready in Ridley Scott’s The Terror

Dr Goodsir is one of the leading characters in Ridley Scott’s The Terror which is the latest fictionalised account of the voyage that ended in cannibalism.

Executive produced by Ridley Scott for AMC, the ten-part drama originally aired in the UK on BT TV and is now being shown on BBC Two and iPlayer.

Dr Goodsir is portrayed in the series by Paul Ready who is best known to British TV fans as stay-at-home-dad Kevin in BBC comedy Motherland.

“You felt like you were really part of something,” Ready said of working on the show.

“I don’t know how rare that is, but it felt special.

“He was always in love with the natural world and the environment, and had great hope for people.

“But I think it was the people that let him down.”

One of the greatest maritime challenges

The series centres on the disastrous attempt by the crews of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror to discover a sea route through the Canadian Arctic to the Orient, with both ships becoming icebound in the Canadian Arctic’s Victoria Strait and the entire 129-man expedition perishing.

Reports of the crew turning to cannibalism while they slowly succumbed to disease and starvation scandalised Victorian society.

The Northwest Passage is around 500 miles north of the Arctic Circle and less than 1,200 miles from the North Pole.

In Franklin’s time, finding it was one of the greatest maritime challenges.

But the prize was lucrative as discovering a way through would open up a new trade route.

Explorers had tried – and failed – since the 15th Century.

To get there from the Atlantic meant dodging thousands of icebergs up to 300 feet in height.

From the Pacific was just as tricky with masses of ice pushed into the Bering Strait.

The fabled route captured the imagination of explorers.

Erebus and Terror made their final stop before the Atlantic crossing at Login’s Well, Stromness, Orkney, for water and supplies.

The ships were last seen in Baffin Bay in the Arctic six weeks later and after this they became part of one the enduring mysteries of the age of exploration.

Since the expedition was equipped with three years of provisions, the Admiralty in London did not send out rescue missions until 1848.

Final expedition was sent from Aberdeen

In total, around 50 rescue missions were launched to find Erebus and Terror, and these expeditions covered new ground, added more details to the rapidly evolving maps, and helped define the territory of Canada.

Lady Franklin decided to send out a final expedition from Aberdeen to clear up the great Arctic mystery which set sail on June 30 1857.

Two years later, on King William Island in the Canadian Arctic they discovered written proof of the death of Franklin and later the rest of his team.

It gave the locations of the ships and said that the crews had abandoned them after they became lodged in pack ice.

It wasn’t until 2014 that a Canadian mission, equipped with all the latest marine archaeological equipment, located Erebus.

Terror was discovered two years later.