She was the youngster who enjoyed a magical childhood in Austria before being forced to flee from the Nazis to a convent boarding school in Aberdeen.

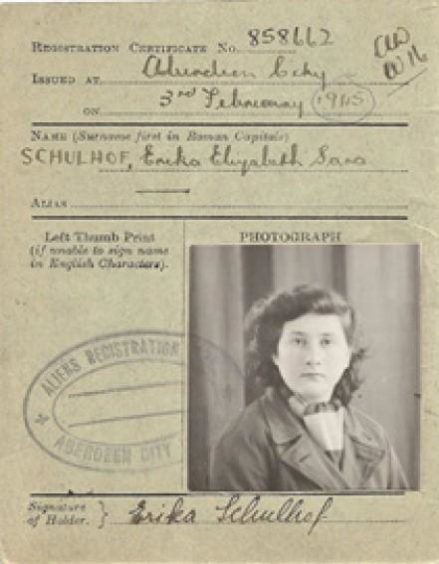

Erika Schulhof has spoken about her extraordinary life, chronicled in her book On My Own, which tells of how she spent more than 60 years trying to discover what had happened to her parents after she travelled to Scotland as part of the Kindertransport scheme which rescued so many Jewish youngsters before the Second World war.

She is now 92 and living with her family in the United States after being a teacher, a volunteer, a poet and a musician in Ohio and Washington DC, but talked about her experiences of living in castles, cottages and a convent in the north-east and meeting people across the region who remained her friends for decades afterwards.

All the while, this resilient, resourceful woman has been determined to tell her story as a tribute to her parents who shielded her from the Nazi horrors swirling all around her: and which subsequently led to their deportation and disappearance.

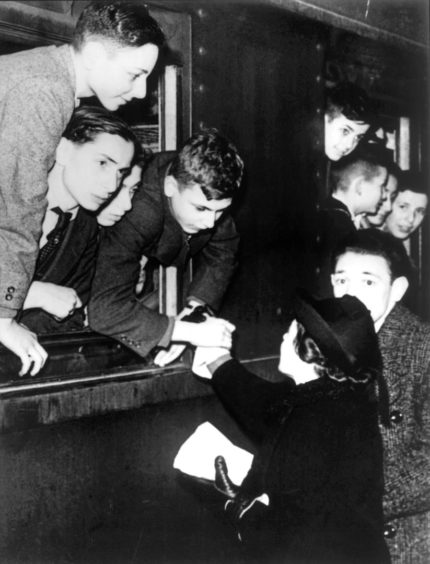

One last wave before the train departed

Fritz and Trude Schulhof’s hearts must have been breaking as they bought their daughter an ice cream on their way to Vienna railway station on May 13 1939, but they hid their emotions when the whistle blew and a train packed full of children began its long journey through Austria, Germany and Holland en-route to Britain.

Erika recalled: “They made me feel I was simply leaving on a nice adventure.

“It was eleven at night and mine was one of the faces pressed up against the window to say goodbye on that fateful day. I watched the two dearest people in my life waving white handkerchiefs so bravely until they disappeared from view.

“I never saw them again, but I wouldn’t know that until years and years later, hoping against hope, that we would be re-united.”

Cocooned in a convent in a Scottish city

On May 17, Erika arrived at the granite mansion at 3 Queen’s Cross, which housed the Sacred Heart convent boarding school in Aberdeen.

She was welcomed with a big hug and Reverend Mary Paterson led her down the long main corridor inside the building.

The uniformed girls curtseyed her as the duo passed.

She later learned that one of her aunts, Ella Popper, was prominent in church circles in Austria and had facilitated the youngster’s move to Scotland.

But these were strange and often frightening times for somebody of her age.

As she said: “My arrival must have been something of an event because the Aberdeen Press and Journal ran a photograph of me on May 18.

“It shows a perplexed-looking ten-year-old and, since I could not understand anybody’s English, I probably did not even know why my picture was being taken.

“I was totally unprepared for what awaited me. Fitting in at a boarding school was so different that I had a hard time finding words to write to my anxious parents.

“But eventually, I began to realise just how kind all the people were being to me.”

Even going to the toilet was an ordeal

Erika doesn’t know how she managed to struggle through the first month in an alien environment.

She couldn’t understand what anybody was saying to her and nobody she met spoke a word of German.

This often led to confusing circumstances while she adapted to her new existence. There was one occasion where she needed to go to the toilet and exclaimed “Closet, closet” with the accent on the last syllable.

As she recalled: “No one could figure out what I wanted. They showed me broom closets, coat closets, every imaginable closet except the one that I was looking for.

“But this was one of the many frustrations that motivated me to learn a new language, which I did with amazing rapidity.”

Erika received a constant stream of correspondence from her parents, which testify to the powerful love and affection which existed between them, even a long distance apart.

She missed them dreadfully, especially when the relatives of other boarders visited the school, but consoled herself with a recurring daydream: “My mother and father are walking up to the convent to come for me and we are having a grand reunion.”

But eventually, the letters arrived no more. And Erika was on her own.

Life in cottages, castles and country houses

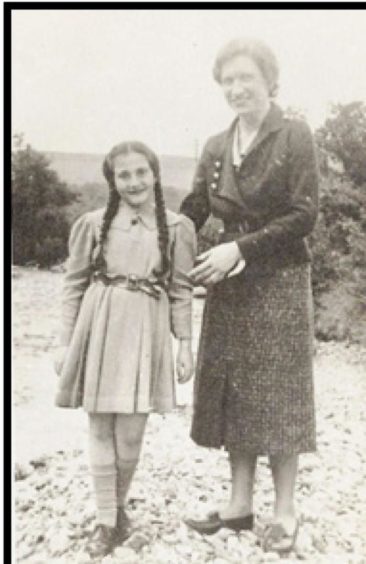

Yet, while she awaited the post, Erika gradually developed friendships with people in her new life.

She spent her first vacation in a hotel in the village of Craigellachie on the banks of the Spey, subsequently stayed with her school friend, Sheila Grant, in Braemar and was fascinated by the caber-tossing when she attended a Highland Games.

She also reminisced about her “ticket to life with the upper crust” when she acted as a child-minder in a stately residence in Ellon and looked after the four little boys who lived with their mum Victoria Ingram and her mother, Lady Susan Reid.

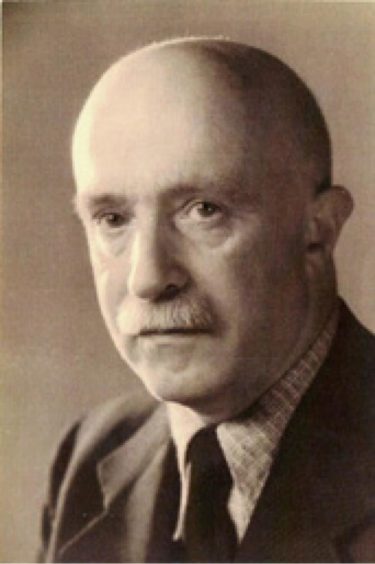

The latter’s husband, the late Sir James Reid, had been Queen Victoria’s physician and had also been the doctor of Edward VII and George V.

It opened the young Erika’s eyes to how some privileged people avoided the worst of the wartime privations but, even as she holidayed at such places as Ellon Castle, Lossiemouth and Letham House, she took people as she found them.

One of her letters read: “I had lunch and tea with Lady Margaret Egerton, Princess Elizabeth’s lady-in-waiting. I met and talked with the king’s nephew and the Queen’s sister and niece. They are simple people, full of fun and charming.”

As the adult Erika added: “Simple people! I was being somewhat blasé.”

Erika’s impression of Aberdeen during the war

After moving to the United States, Erika met and married an American journalist Walter Rybeck and he chatted to his wife about the special memories she had of her years in and around Aberdeen.

These are some of the things she has never forgotten.

“One of my strong impressions of Scotland was the cold. Because it was war time, coal was needed for soldiers and battleships. Our classrooms in Aberdeen were so cold that we wore gloves so we were able to write and even then, our knuckles turned bloody.

“I was amazed to see men in pleated skirts, because nobody had told me about kilts. Also new to me were foods unlike those I was used to in Austria. There was fish for breakfast, which I came to like, and porridge, which I didn’t.

“When the boarding school students went home for vacation, I sometimes went with them. At other times, I went to stay with friends of the nuns. In all cases, people were so kind and hospitable and I just accepted this without question at the time.

“But now, I realise that my hosts made many sacrifices to take me into their families and treat me so well. I was especially close to the Grants in Braemar, whose youngest daughter, Sheila, was a classmate my age.

“It was only as I grew older and lived in different places that I realised how unusually wonderful the Scottish people were to me.

“We took walks from Queen’s Cross, and we always carried gas masks like pocket books. We would see bombed apartments and, with walls missing, the bedrooms and living rooms would be exposed. We also walked to Rubislaw Quarry – so deep and scary – and it was still in operation at the time.

“Aberdeen was a regular target for German bombers on their way from Norway to London. We girls prayed that they would bomb after midnight – because, if that happened, we would be allowed to sleep later in the morning!

“I couldn’t believe how purple the Scottish hills became when the heather [my own name] bloomed. Looking back, I loved Aberdeen and the many beautiful parts of Scotland that I was able to visit.”

How Erika finally dismantled the wall of silence

Erika Schulof Rybeck spent more than half a century striving to find out what had become of her parents after they waved her goodbye in 1939.

Although she regards herself as one of the “lucky” children who escaped from tyranny, persecution and extermination, she struggled to gain answers despite writing to “every possible organisation” in America, Austria and Israel.

In 1996, Erika was sent a letter from the Red Cross, informing her they were still working to trace what had happened to Fritz and Trude during the hostilities.

She was told they had been deported from Vienna on October 23 1941 on a train headed for Lodz in Poland. At that point, the trail went cold – or at least it did until 2002 when she discovered the truth from her son Rick and his wife Ellen Czaplewski.

She had prepared herself for the worst. And she was right to have done so.

‘How could my parents have vanished into thin air?’

Rick Wybeck learned that when the Lodz Ghetto was liquidated, Erika’s parents were sent to Chelmno in northern Poland on May 9 1942, leaving at 7am and arriving in the afternoon.

He wrote: “Chelmno was not a concentration camp, but purely a death camp, prior to the invention of gas chambers. Prisoners were forced to disrobe before being put into the cargo hold of trucks which were sealed off.

“Then, truck exhaust was piped in as the truck drove around until people stopped moving. The bodies of those who perished were dumped in a nearby forest.”

Erika had feared such news for many years and yet she was proud of the diligence which her son and his wife had demonstrated in uncovering the ghastly details.

She said: “No longer would I have to await letters telling me: ‘Proof of death is not available’ or ‘No information has become available yet’.

“It was tragic, but knowing the awful truth is a relief after spending most of my life trying to fathom how my wonderful parents could have vanished into thin air.”

Erika Schulof Wybeck’s poem about “Searching”

“We sift through the ashes of our past,

“Children no more,

Yet searching forever,

For the lost years,

For the lost tears,

For the lost faces,

For the lost places,

Of our lost childhood.”

On My Own by Erika Schulof Rybeck is published by Summit Crossroads Press.