It was the most destructive, lethal and all-encompassing conflict in human history; one that claimed the lives of between 70 and 85 million people from 1939 to 1945.

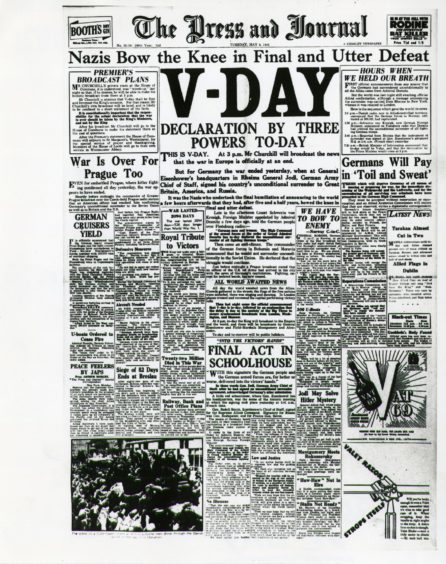

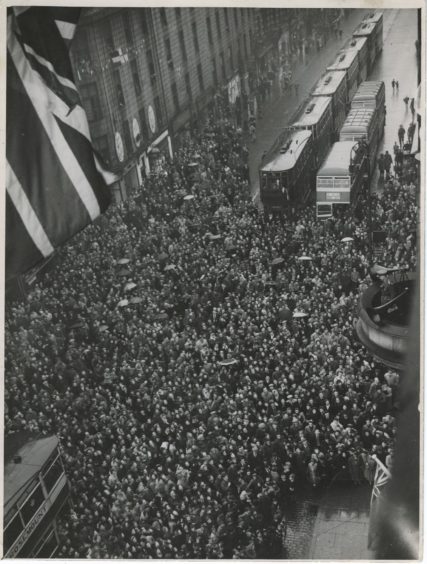

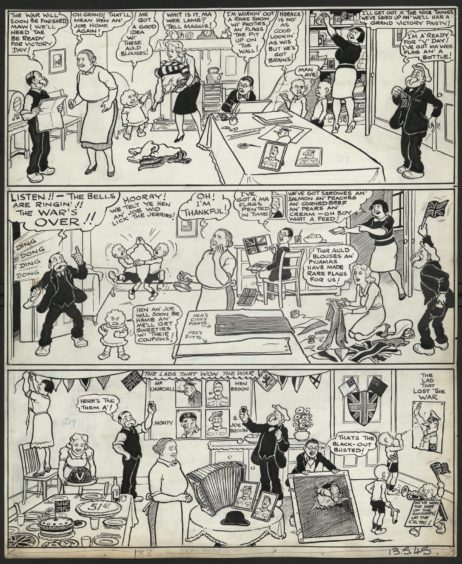

So it’s hardly surprising that VE (Victory in Europe) Day on May 8 1945 was greeted with rejoicing, relief and a resounding “Thank God” by people across the UK who had witnessed the struggle throughout the Second World War – from Dunkirk and the Battle of Britain to such defining chapters as Pearl Harbor, the siege of Stalingrad, El Alamein, Arnhem and the courage, slaughter and sacrifice of the Normandy landings on D-Day.

The hostilities, which continued in Asia until August and the dropping of atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, inflicted a grievous toll on every corner of the globe, but the celebrations throughout Britain on VE Day marked the beginning of the end of nearly six years of blitzkriegs, bombing raids and blackout shelters.

Pauline Anderson, a nurse from Inverness, was among the tens of thousands of people who were working in London as the festivities began, following the news of the German surrender.

She wrote to friends: “You would never have believed it unless you were there.

“Me and Fiona (her friend) went down the Mall to Buckingham Palace and the streets were full of people waving flags, singing Rule Britannia and God Save the King and the older men and women shook our hands and thanked us.

“We saw King George VI, Queen Elizabeth (the late Queen Mother), and their daughters, Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret, who appeared on the balcony, and we cheered ourselves hoarse.

“There was such a wonderful feeling of pride and joy among the crowds that we will never, ever forget it.”

It was a time for a national outpouring of joy and the pubs ran dry. Yet many troops were still involved in conflict and others would not return home until the following year. Here are some of the contrasting memories of VE Day.

Murray Haddow fought in the Arctic Convoys

Murray Haddow was just a teenager when he came face to face with the dangers and devastating loss of life which were part of serving on the Arctic Convoys that maintained crucial supply routes to Russia throughout the Second World War.

But the Monifieth man never forgot the appalling scenes he witnessed when one of his sister ships was torpedoed by a U-boat and he was standing on deck as the explosion rapidly tore the vessel to pieces.

He and his colleagues attempted to launch a rescue operation, but the sea was unrelenting and Mr Haddow noticed the lights flickering on the stricken men’s life-jackets as they slowly drifted off to their deaths.

The work didn’t stop even on VE Day, while most of the Allied forces celebrated the cessation of hostilities.

Instead, in May 1945, he and his colleagues found themselves involved in one final encounter with the enemy who had terrorised them for so long.

He said: “I vividly remember being on board HMS Caprice – alongside her sister ship HMS Cavendish – in Loch Eriboll in the far north-west of Scotland when the German U-boat 516 emerged from the depths to surrender.

“We knew, as soon as she surfaced and we saw the black flag, that there would be no more torpedo threats, no more loss of life on the ocean in the war.

“I went on six of these convoys after joining up as an 18-year-old in 1944 and they were grim. There was the constant menace of bombardment from above or submarines from below, and that is before you consider the weather conditions, the ice, the storms and the fierce winds that affected the ships.

“It’s strange, but I don’t recall being frightened when I was on these missions, because I was only a boy, I was with people I trusted, and there was a general feeling that we were all in the same boat, so we just had to get on with it.

“When the war ended, it was a relief as much as anything else and, although we couldn’t think about celebrating until we had actually returned home to our families, we were overjoyed it was finished.”

David survived the horrors of St Valery

Even now, 80 years after he was one of the thousands of Scottish troops caught up in the carnage and bloodshed at St Valery-en-Caux in June 1940, David Beaumont from Invergordon can remember the visceral feelings of fear and apprehension that gripped the 51st Highland Division as its troops attempted to halt a German blitzkrieg in its tracks.

He had just turned 19 at the time, and had never experienced anything like the stark choice that was offered to thousands of men – kill or be killed, face insurmountable odds or surrender to the enemy – as they held up the German Army long enough to allow the mass evacuation of British troops at Dunkirk.

But, while the latter operation was successful, there was no reprieve for the Highlanders, including Mr Beaumont who turns 100 later this month.

He said: “It’s hard to describe the events of these few weeks and the huge impact which they had on so many people.

“We did the best we could and held out as long as it was possible, but there was death and destruction all around us.

“We were scared, because it was a hopeless situation. There were no (British) aircraft flying over us who might have helped, so we were on our own.

“We knew there were only two outcomes – we would either be killed or we would be captured – and that is difficult to accept when you are a young man who has never experienced anything like it before. But we made a difference.”

After the men were forced to surrender, he was transferred to Stalag VII-B Lamsdorf and he and his fellow Scots had endure a gruelling route to the prison camp in Poland as the prelude to being inflicted with strength-sapping work patterns and meagre food rations from their captives.

But, remarkably, Mr Beaumont refused to become depressed or accept his situation, his spirit of defiance never left him throughout all the months of incarceration and he was constantly seeking a means of eluding his captors.

One day, while out with a working party on a sugar beet farm, he and two of his fellow POWs escaped and made their way to territory that was held by Russian forces.

In a matter of weeks, they were back with the Allies, transferred to Prague and into the hands of US forces who promptly had them repatriated to Britain.

He said: “Looking back, it was a challenge to keep everything together in the camp, but there was a lot of camaraderie between the lads. We were all in it together and I was able to get away with a couple of my mates.

“We gradually learned that the Russians weren’t too far away from where we were imprisoned, so we waited for our chance. And then, while on the farm, we took the high road and slipped away and were picked up by the Russians.

“It all passed by very quickly. One moment, we were in Poland, then we were on our way to Prague, and we were meeting up with the Yanks and finally returning home.

“I didn’t get back to the Highlands (he now lives in Brora) until after VE Day, at the end of 1945, but I wasn’t put off by what we had gone through during the war.

“I relished the military life so I re-enlisted and ended up going all over the world (including a posting in Singapore) in the years ahead.”

Hugh enjoyed a busman’s holiday on VE Day

Hugh Inkster was among the millions of Britons who celebrated the end of the Second World War in Europe.

But he must have been one of the few Scots who marked VE Day by spending the night in a London double-decker bus.

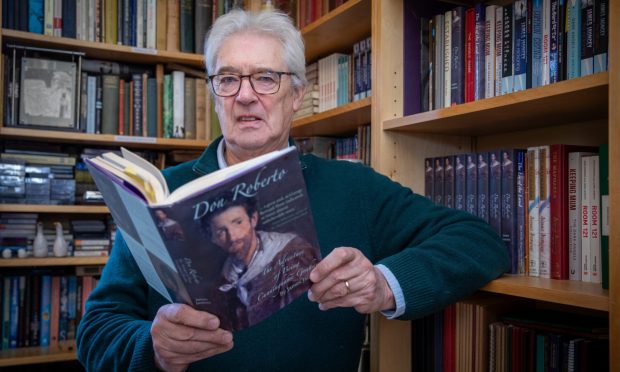

As a teenager who had grown up in rural Aberdeenshire, Ballater-based Mr Inkster went on to spend more than 40 years in the military and, even today, in his 90s, he has a sharp memory and a steely determination to ensure that the sacrifice of those who perished during the conflict is never forgotten.

Indeed, he has preserved and maintained the war memorial in the Deeside community with such unstinting care and attention that it has regularly been recognised as one of the best in the whole of Scotland.

He vividly recalls the circumstances that led to him enlisting towards the end of the hostilities in 1945.

He said: “I was about 18 years old and I remember being told we had a one-in-ten chance of being sent down the mines.

“I had grown up in the countryside at Crathie – my father was the electrician at Balmoral – and I didn’t fancy that at all, so I joined the army and I did my basic training as VE Day approached.

“I was down in the south of England and we were given three days off. So we travelled up from Woking to London Waterloo and there was this massive party going on.

“We joined the crowds in the streets and we were singing, dancing, celebrating wherever you looked and it was like the Coronation and the Diamond Jubilee in one.

“There was a group of us who finished up in an empty double-decker bus.

“We slept in it, I was on the top deck, and we were excited by what was happening.

“It was innocent fun – I know that the bars were doing a roaring trade, but we didn’t need alcohol, we were young, we were soaking up the freedom and the chance to have a laugh and escape from the normal day-to-day life.

“Eventually, I ended up in India, two months after VJ Day (in August 1945) and I liked being a soldier so I signed up with the Royal Artillery for seven years – and I ended up doing 42 years!

“I spent 20 of these in the sergeants’ mess, then became a commissioned officer and a Lieutenant Colonel before retiring and returning to the north-east, but I like to keep active and find things to occupy my mind.”

There may be fewer and fewer of these veterans left to highlight the qualities of courage and comradeship that made VE Day and VJ Day possible, but their voices are still worth heeding.