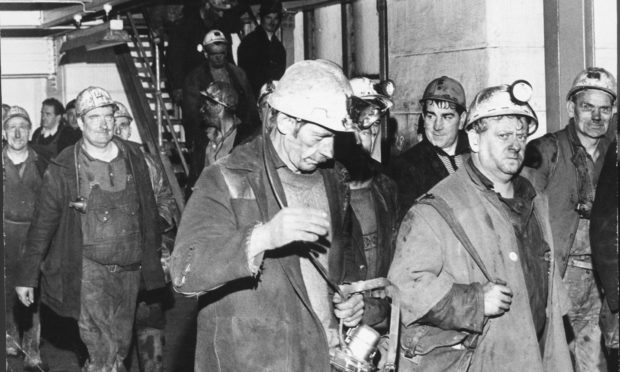

The flooding of the Longannet complex in Fife brought centuries of mining to an end in 2002. A new book is now looking back at Scotland’s lost coal mines and tells the stories of the miners and their families that were at the heart of pit life.

Ewan Gibbs’ Coal Country details the end of Scotland’s coal mining and the industry’s advocation for a devolved Scottish Government – well before the changes were implemented.

Coal mining at the centre of cultural changes

Ewan, who is currently a lecturer at Glasgow University, became interested in the end of coal mining in Scotland when he began to realise the significance between coal mining and major changes in Scottish politics.

He explained: “The book is about the end of coal mining in Scotland which is often associated exclusively with the 1980s and my argument is that it is actually a much longer and more interesting story.

“Across the second half of the 20th century the economic, social and political landscape of Scotland fundamentally changed and that was associated with falling employment in coal mining and the coalfields were at the centre of those cultural changes.

“My argument is that experience of closures encouraged a more, what I call cosmopolitan feeling amongst Scottish coal miners where different parts of the coalfields would all work together.

“That also explains in part why the Scottish Miners Union became such a strong advocate of a devolved Scottish Parliament from the late 1960s. Significant changes in Scottish politics were associated with those developments.

“Essentially miners were responding to the shrinkage of the industry and its centralisation and control from London and part of their response to that was to argue for devolution and for control over important decisions in their community that relates to government to be made in Scotland.

“Some of the changes we associate with Scottish politics in the 21st century in my view have important origins in developments that took place in the 1960s and 1970s especially in the Fife coalfield.

“The coal miners were absolutely essential to the visible working class presence in politics. That would have been particularly true in Fife where historically there was a strong overlap between coal mining and membership in the communist party.

“The politics of devolution-era Scotland I think are anticipated by experiences of deindustrialisation and political responses to that.”

The Fife Coalfield

The Fife Coalfield was one of the largest coalfields in Scotland with over 50 collieries coming in to operation at various times from the mid 1800s.

The extensive coalfield saw the creation of new towns such as Glenrothes during the second half of the 20th century with Ewan explaining the importance of the area.

He said: “Fife is essential because it was by the 1950’s Scotland’s largest coalfield. It then experienced the contraction of employment over a long time period and it is also interesting because some of the changes in the mining industry were most visible in Fife.

“You have the building of Glenrothes new town which experienced significant immigration from Lanarkshire and other coalfields when closures were taking place in the late 1940s.

“There was also the building of Longannet Power Station which was built in the 60s and that provided employment for large numbers of miners from across Scotland that commuted to work there.

“That period of time between the designation of Glenrothes and the closure of Longannet in the early 2000s covers the extent of the book really.”

Longannet coal mines

Longannet was established in the 1960s on the north side of the Firth of Forth. It connected the Bogside, Castlehill and Solsgirth Collieries to form a single, five mile long tunnel which would provide power to the nearby Longannet Power Station.

The Bogside Colliery closed in the 1980s, and by the early 1990s, the Castlehill and Solsgirth coal reserves were exhausted.

In the late 1990s, new “roadway” tunnels were driven to access a coal seam beneath the Forth, downstream of the Kincardine Bridge.

When production from Castlebridge ceased, in 2000, the northern side of the complex was sealed off and flooded. Dams were constructed, isolating the old workings from the active Kincardine working.

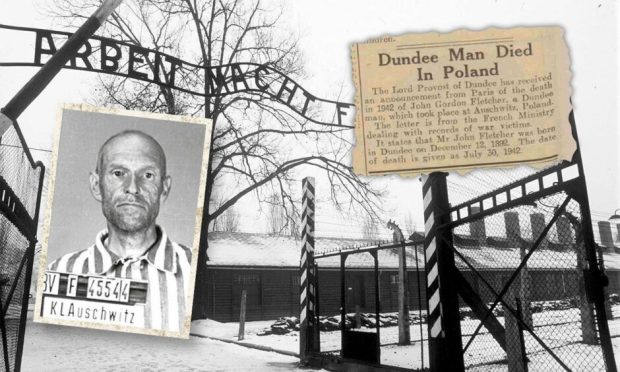

In March 2002, millions of gallons of water flooded into the underground pits.

There were 15 people below ground at the time who were all luckily in another part of the mine, enabling them to be evacuated safely.

The flooding saw the end of Longannet and the end of deep mining in Scotland.

The site would be fully demolished in 2019 with the adjoining power station closing in 2016.

The families behind the mines

Coal Country also features interviews with those who were at the heart of the pits and their families, discussing what the industry meant to them.

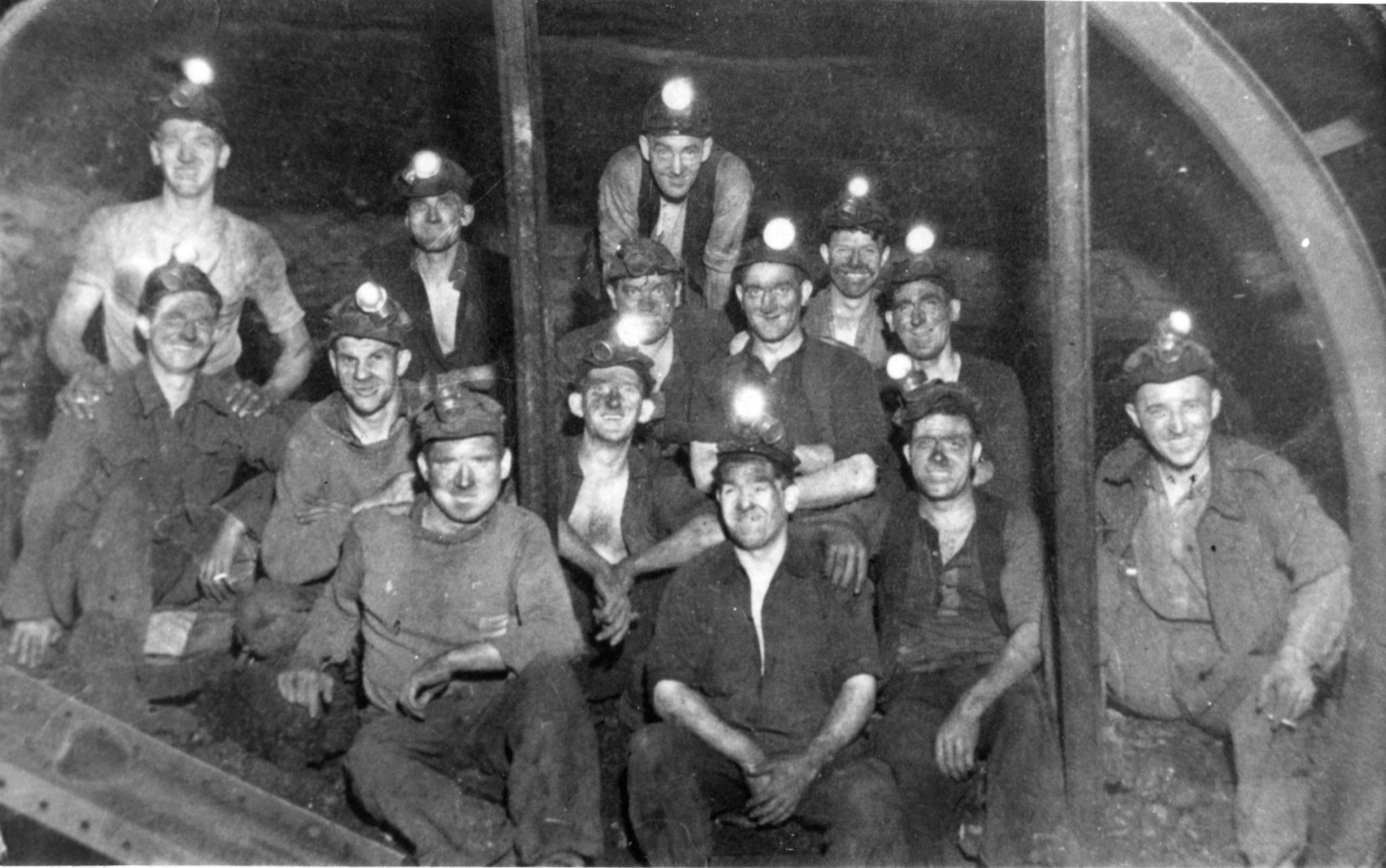

Ewan said: “In the interviews we discuss what it was like firstly to come from a mining family and to work in the industry from a male point of view.

“Most of the men I spoke to were following their fathers and a lot of times their grandfathers into the mining industry they were responding to social expectations and awareness of the economic rewards that mining offered. It was seen as a high wage payer by the 1970s.

“We also discuss the life of communities such as the importance of annual gala days, importance of miners welfares in providing social activities, football teams, tennis courts, dancing and all sorts.

“That also included trade unionism and the experiences of industrial action. One other really important part of the interviews was changes in gender relations and these changes have not all been entirely negative particularly the development of larger scale employment of women in the second half of the 20th century.

“That included industrial employment and large new factories which were brought to the coalfields such as the huge electronics in Glenrothes. These new factories were seen as clean and safe and comparatively well paid so they provided important economic opportunities which were there for women as well as men.

“That in turn means that deindustrialisation directly impacted women as well so when factories closed or downsized women lost jobs too which I think is important to reflect on.”

Coal Country is available to read for free online or can be purchased in paperback or hardback.