In 1935 Dundee was given a view across the night sky like no other when Mills Observatory was finally opened after the development was stalled for over 20 years.

Following yesterday’s solar eclipse it seemed like the perfect opportunity to dive in to the history of the UK’s first purpose-built public astronomical observatory, complete with a papier-mâché dome that has withstood eight decades on Balgay Hill.

John Mills

The observatory wouldn’t be what it is today without Dundonian John Mills. A linen and twine manufacturer by day, Mills was a keen astronomer by night and even created his own private observatory on the slopes of the Law, near what is now Adelaide Place.

Mills was also a member of the church and was heavily inspired by Reverend Thomas Dick who was a philosopher as well as author of a number of books on Astronomy and Christian Philosophy.

The reverend was keen to show that science and religion could go hand in hand, believing that the greatness of God could best be appreciated by the study of astronomy, to which he devoted his life to. He also advocated that each and every city should have public parks, public libraries and of course – a public observatory.

Although John Mills passed away in 1889 but wanted to ensure Dundee would continue his astronomical work, leaving a bequest to Dundee Town Council with the terms of building an observatory in the city.

Set backs and changing plans

After the town council received the bequest they were unsure how exactly they would be able to fulfil Mills’ wishes as they had no experience of a bequest of its nature.

Hoping they could help, the council decided to offer the money to the Dundee University College in the hope that they would be able to fulfil its terms.

Seeking expert opinions from the likes of the Royal Greenwich Observatory, regarding the feasibility of such a project, the advice they received didn’t paint a positive picture and it was thought that only very limited public access would be possible so the College declined the money, deciding that the project didn’t fit in to their plans.

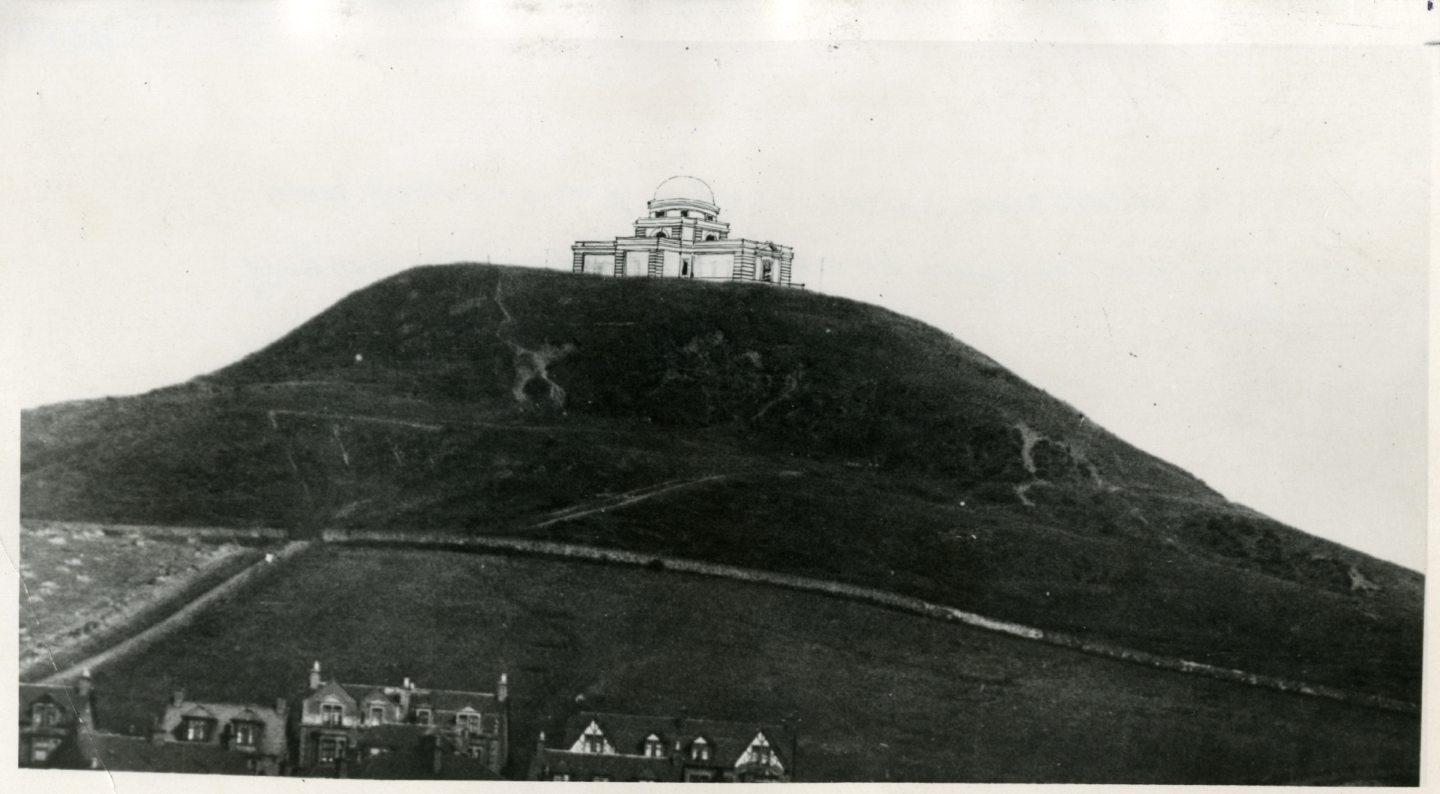

A Trust was then set up within the Town Council, and plans began to build the observatory on the summit of the Law.

As the plans were created the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 put the whole project on pause.

Not only could they not continue with the construction but the intended site was instead reserved for the War Memorial, which was erected after the end of the war.

It wouldn’t be until the early 1930’s that the team were back to the drawing board and with the great Depression came the idea that the observatory would bring much needed work for the local construction industry.

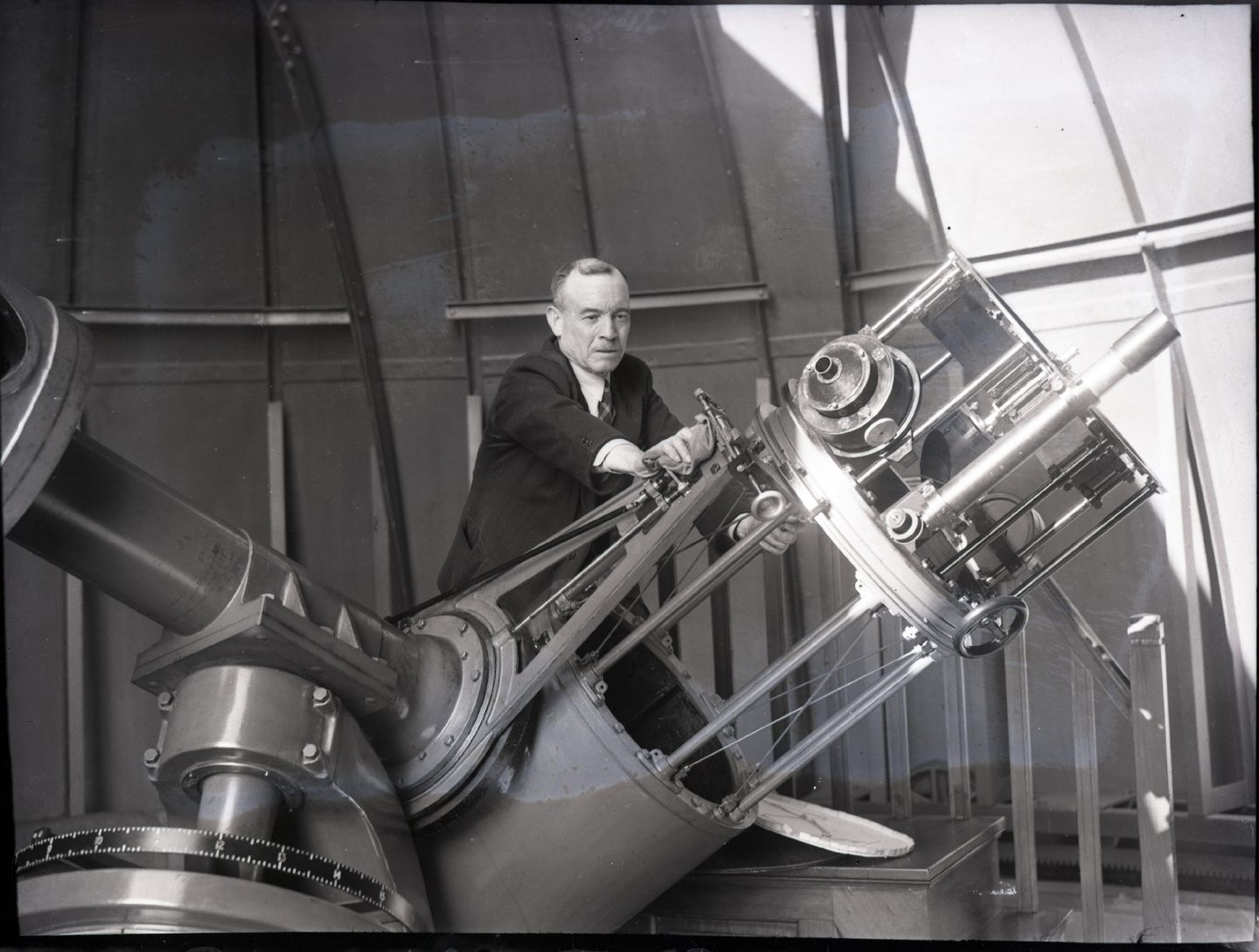

Scotland’s Astronomer Royal, Professor Ralph Samson, was brought in as a consultant for the project and he would prove to be a fantastic asset.

Following examinations of several sites he came down strongly in favour of Balgay Hill as being by far the most suitable, both for its astronomical suitability and also for public access. With the site looking on to the river estuary and the sky protected from the main lights of the city by trees providing a purer atmosphere.

Construction and opening

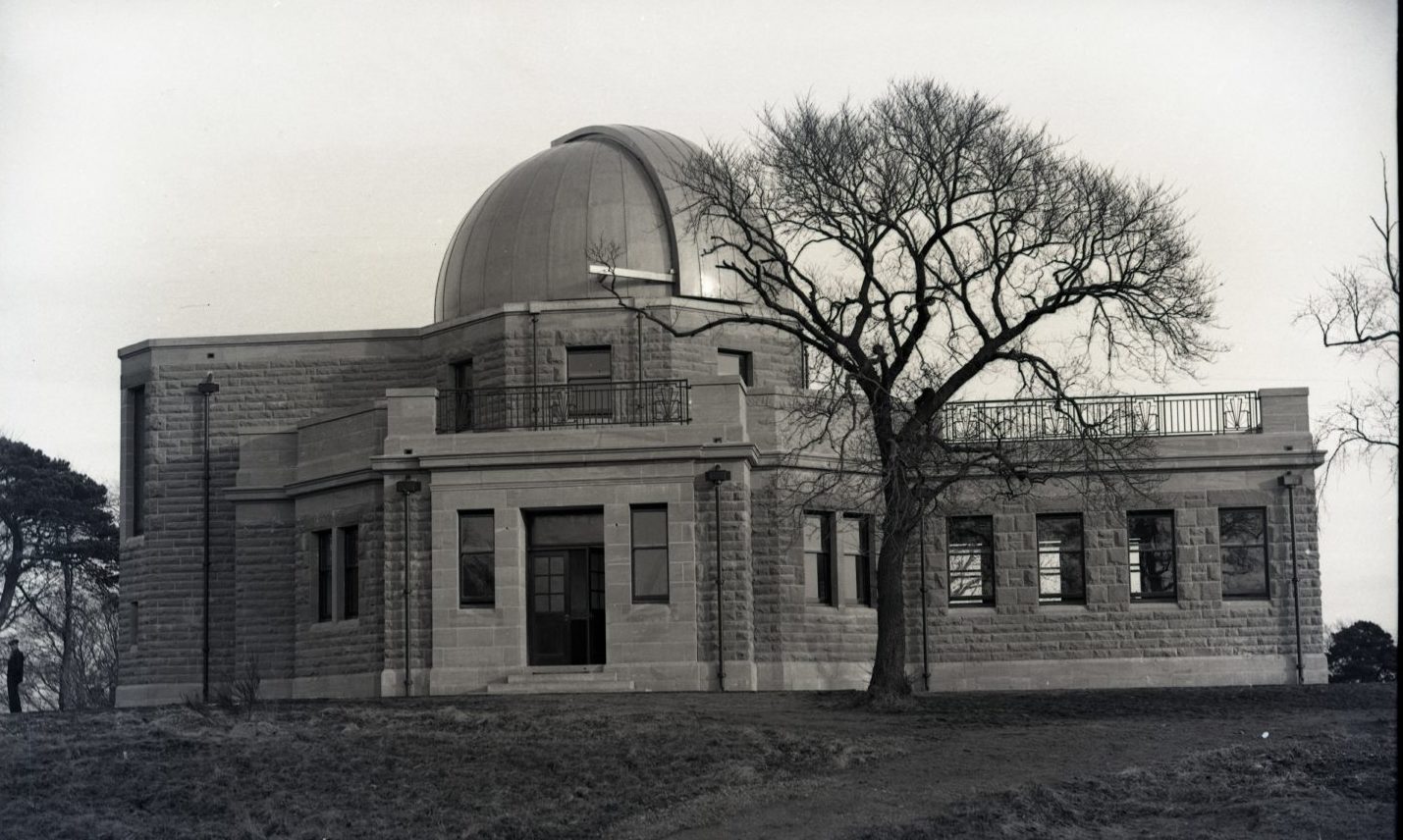

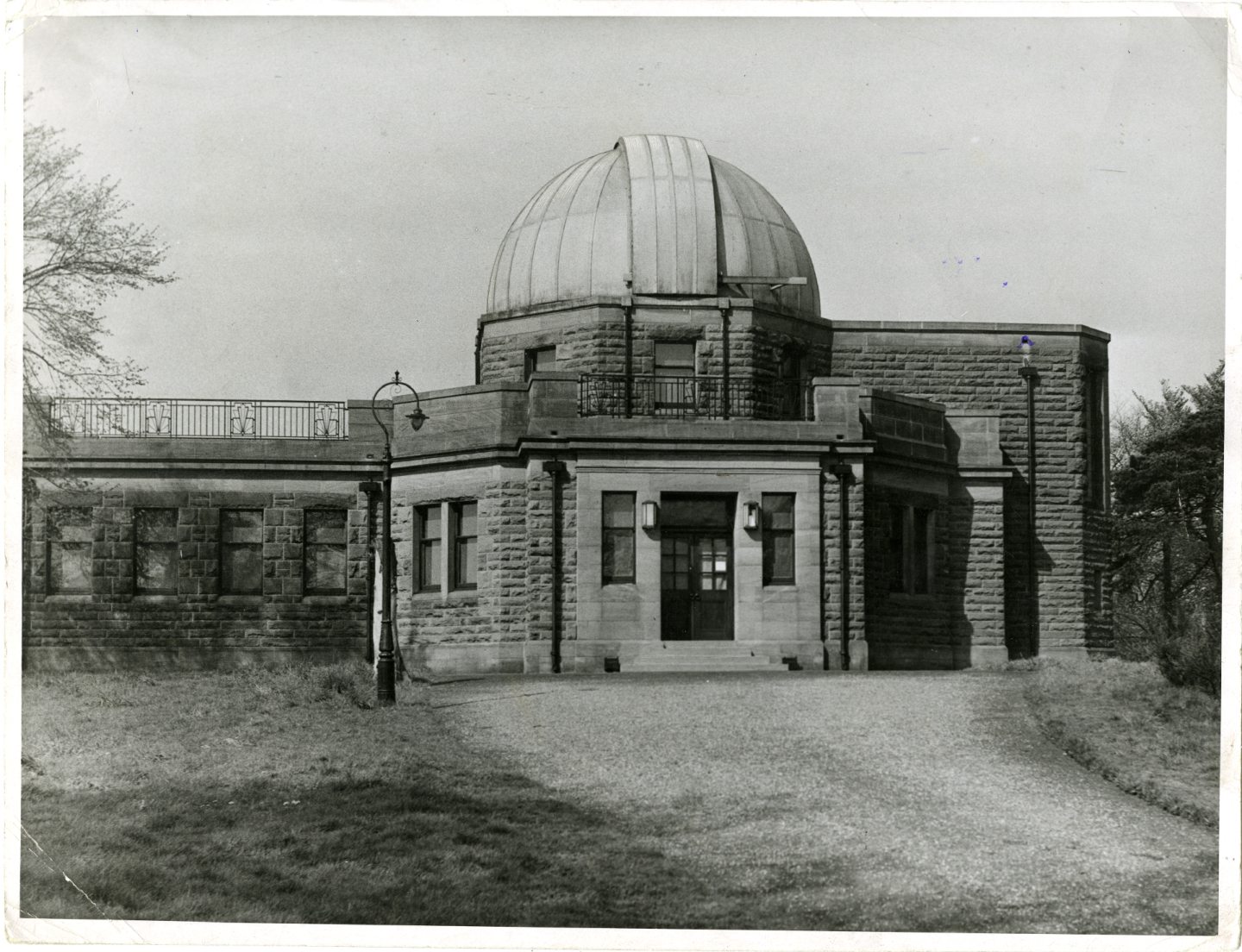

Professor Sampson collaborated alongside city architect James MacLellan Brown to design a much more modern building than the one originally planned before the war.

They decided on a sandstone structure with the blocks quarried from Leoch, near Rosemill.

One of the building’s most unique features is not the seven metre dome itself but more what the dome is made of – papier-mâché.

Despite other observatories featuring the unique construction material, Mills Observatory is the only one still to have the dome in place to this day although it has been restored with waterproofing materials at least twice in its history.

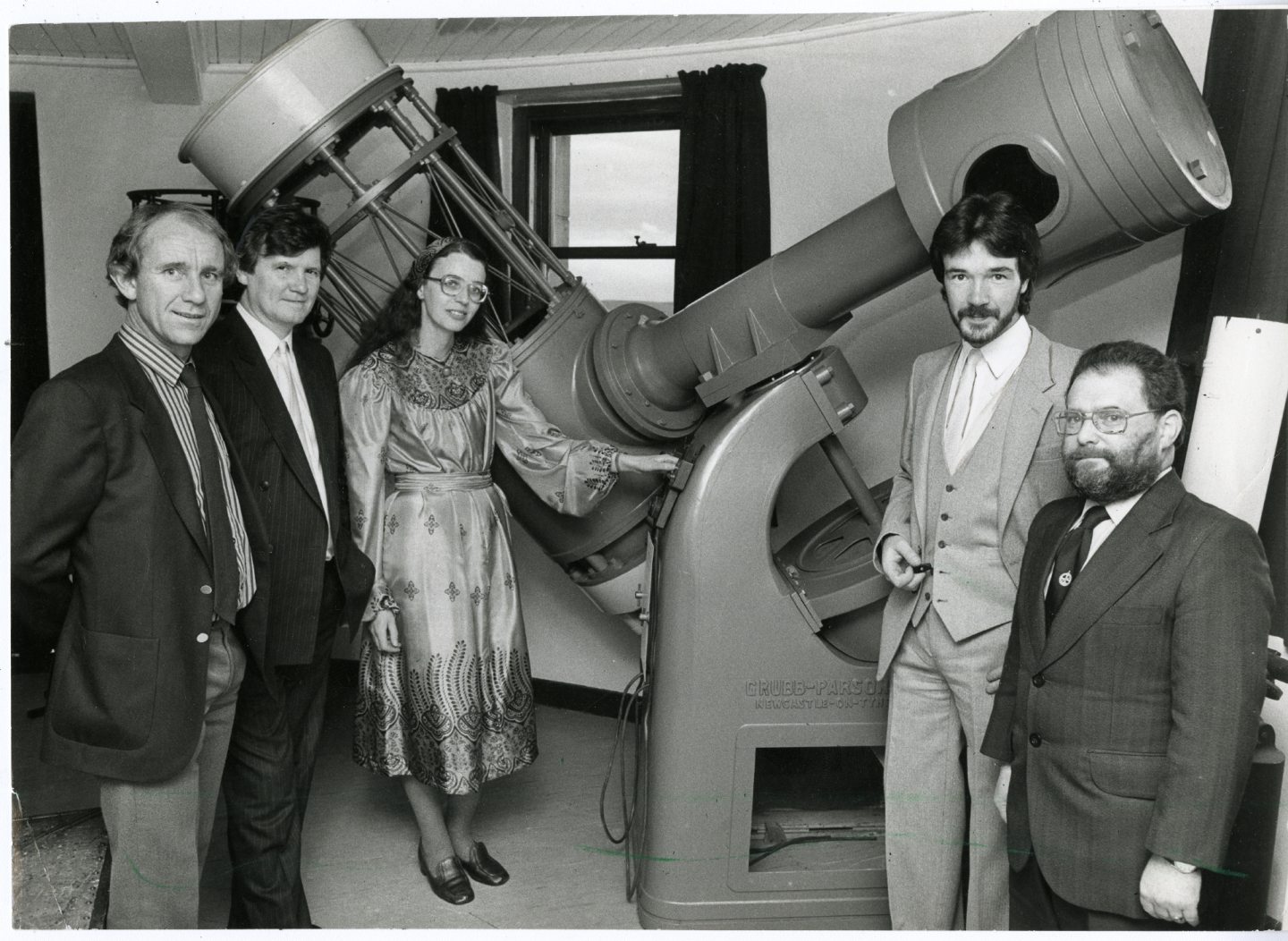

The dome was built by Grubb Parsons and is hand-operated with a steel framework.

The Observatory was formally opened by Professor Sampson on 28 October 1935, and presented to the Town Council by Mr Milne of the Mills Trust in the presence of Lord Provost Buist.

A message of congratulations was sent by the Astronomer Royal at Greenwich, Sir H Spencer Jones.

The observatory’s telescopes

The original telescope given by the Mills Trust was an 18-inch Newtonian reflector by Grubb Parsons and was electrically driven. The remains of the original telescope can be seen in the upper display area of the Observatory.

By early 1951 Mills Observatory was home to a 19-inch pilot model however although it was described as “the first of its kind in the world” it unfortunately was purely for photographic work and so not as useful for the amateur public to use.

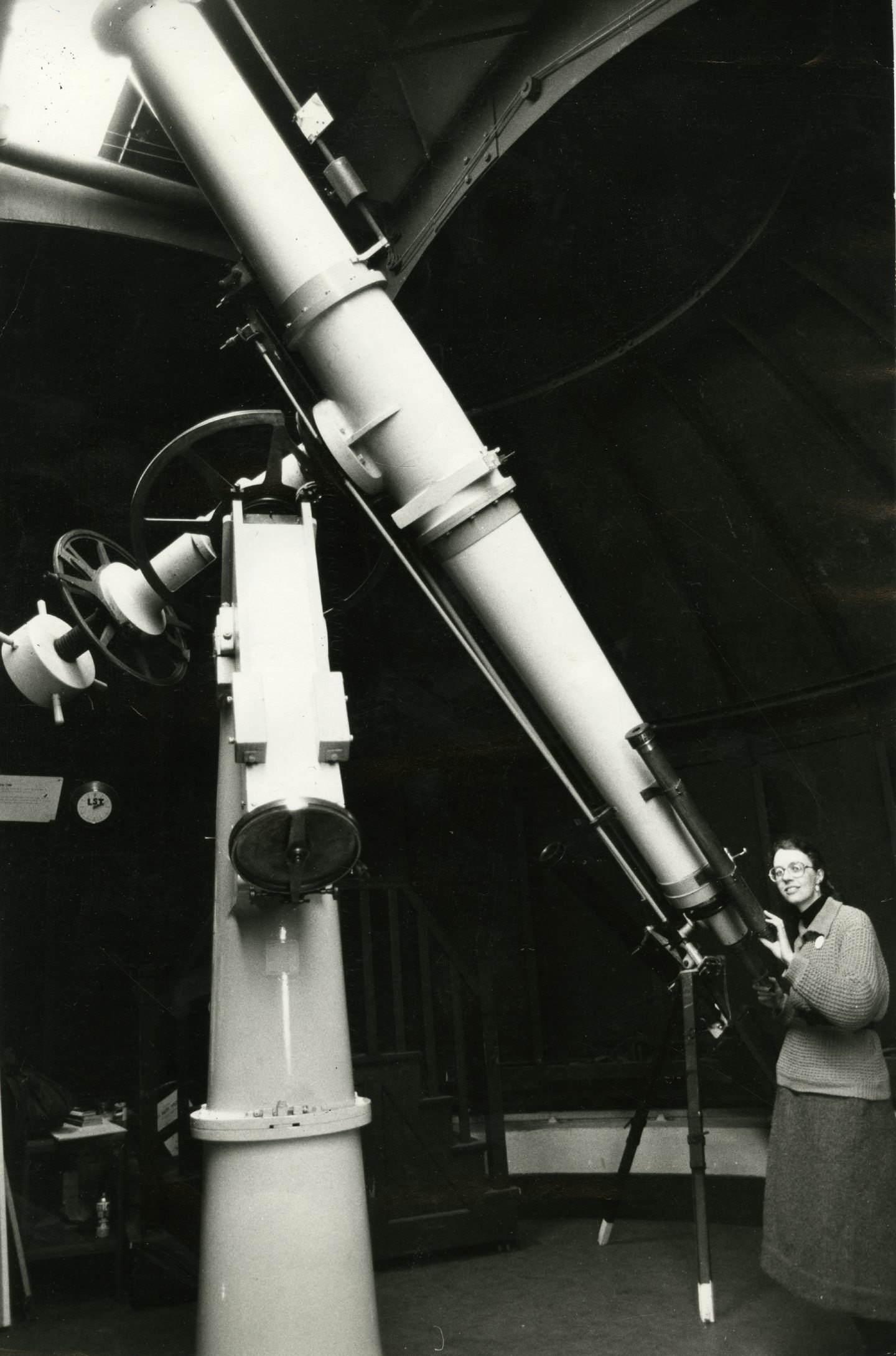

In February 1951 it was suggested that the pilot telescope be transferred to St Andrews University Observatory and the Mills Observatory would then receive the 10-inch Cooke refracting telescope formerly used as a student training instrument in exchange.

At first the Town Council refused.

Professor W.H.M. Greaves, had succeeded Professor Sampson as Astronomer Royal for Scotland, and was called upon to advise on the matter. In view of the scientific benefits of the move, and lack of interest shown by University College Dundee, he recommended that the transfer take place.

This was done at the university’s expense, and on the understanding that the two telescopes were on mutual loan. The 10-inch refractor had to be modified slightly to fit the Mills dome, and the dew-cap couldn’t safely be used. However, it proved to be a much superior instrument for public viewing than the old Newtonian reflector.

Originally built in 1871 it had been privately owned by Walter Goodacre, president of the British Astronomical Association (BAA), who lived in the village of Four Marks, near Winchester.

The telescope was used there by many famous amateurs involved in the work of the BAA and was always described by them as “the excellent 10-inch Cooke refractor”. It was particularly good for observing fine lunar and planetary detail and although not designed for photographic work, the lens is so good that, with modern cameras, good photographs can be taken.

The main telescope is now a 16 inch Dobsonian reflector which provides spectacular views of the Moon and planets and breath taking views of deep space objects.

The Observatory now also has a 12 inch Meade Schmidt Cassegrain reflector which is fully computerised and can find 30,000 objects in the sky and a solar telescope which allows viewers to observe the sun safely during the summer months.

The Observatory also acquired a number of smaller telescopes over the years.

Discoveries and inspiration

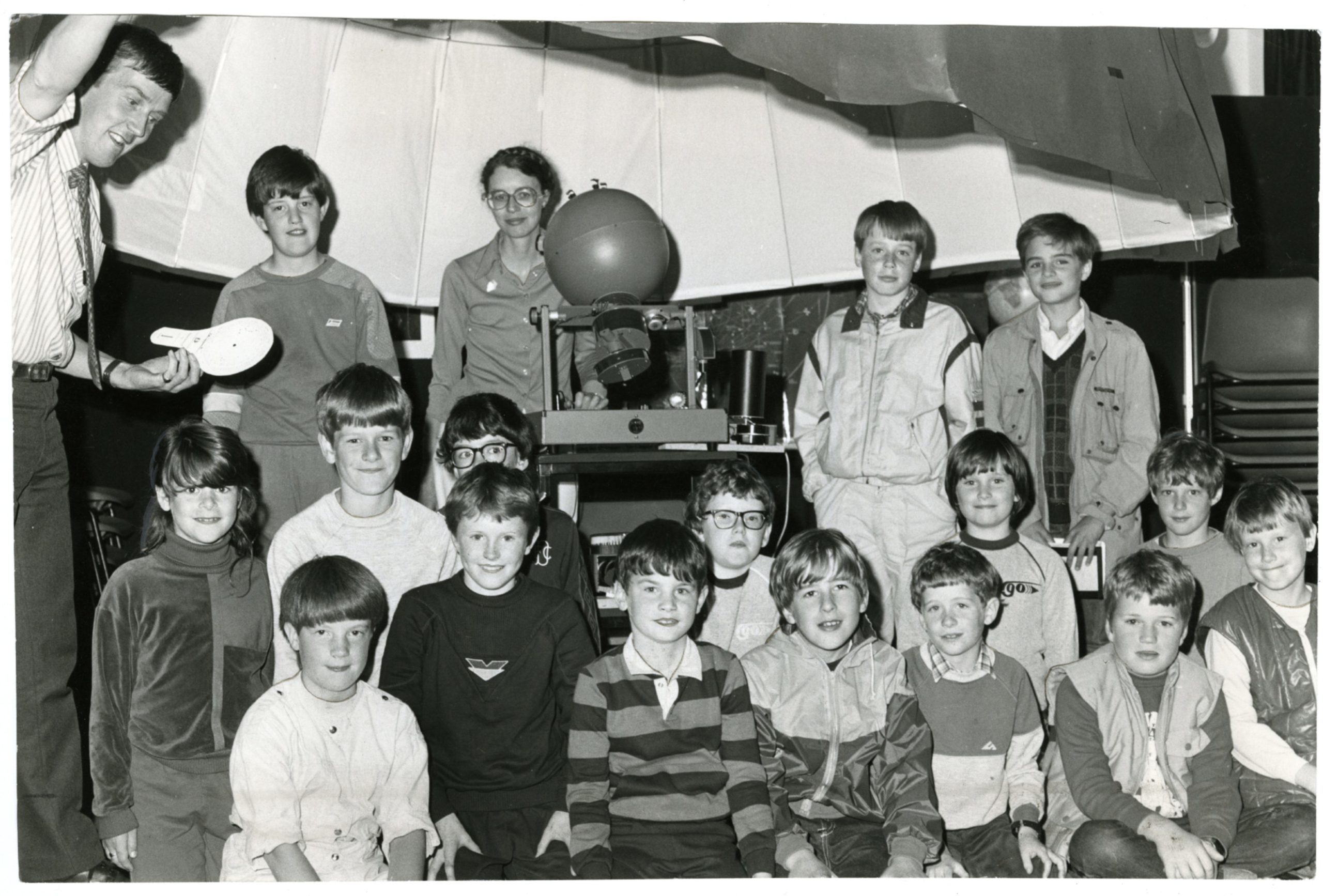

Ever since its opening to the public the Observatory has continued to inspire generations and has also led to some out of this world discoveries.

While attending St Andrews University, astronomer Robert H. McNaught was a regular visitor to the Mills Observatory and became a friend of former curator Harry Ford.

In 1990 he discovered two minor planets, 6906 John Mills and 6907 Harry Ford, paying homage to his friend and also the Observatory’s name sake.

Harry Ford took up his duties in 1967 and organised a number of exhibitions and “Open Days” were held at which the work of the local amateurs was exhibited, over the years that followed.

Ford also organised displays of the work of the Observatory and the local Society at the BAA’s Exhibition Meetings in London, which excited great interest among the assembled amateurs, and resulted in many of them making a special journey to Dundee during their holidays.

Well known TV and radio personality Dr Patrick Moore, praised the work of the Observatory as being “quite unique in his experience.” He himself has visited the Observatory on a number of occasions and opened the improved facilities in June 1984.

During his speech at the unveiling, Dr Moore said that in the future, as in the past, the Mills Observatory would play a great part in the furtherance of amateur astronomy in Britain, and inspire some to take up astronomy as a career.

In 2005 the Observatory hosted its very first visit from an Apollo astronaut when David Scott, commander of Apollo 15, visited the city.

Solar eclipse

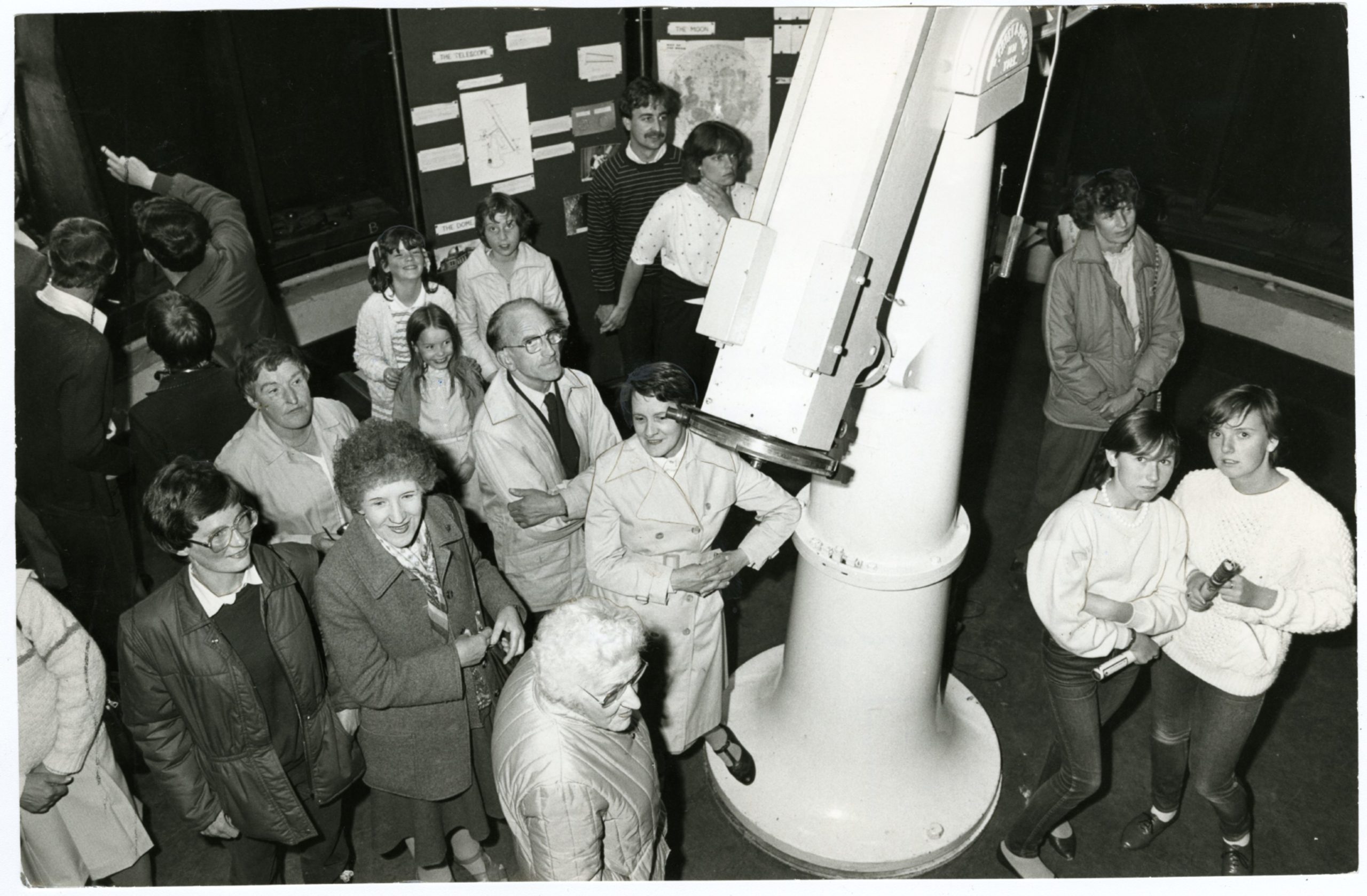

Unfortunately the venue remains closed due to Coronavirus restrictions and was unable to be used for the partial solar eclipse on June 10 2021 however the site is no stranger to crowds gathering for a piece of the eclipse action.

There wasn’t too much room in the Observatory in May 1984 as locals hoped to catch a glimpse of the upcoming eclipse from the dome.

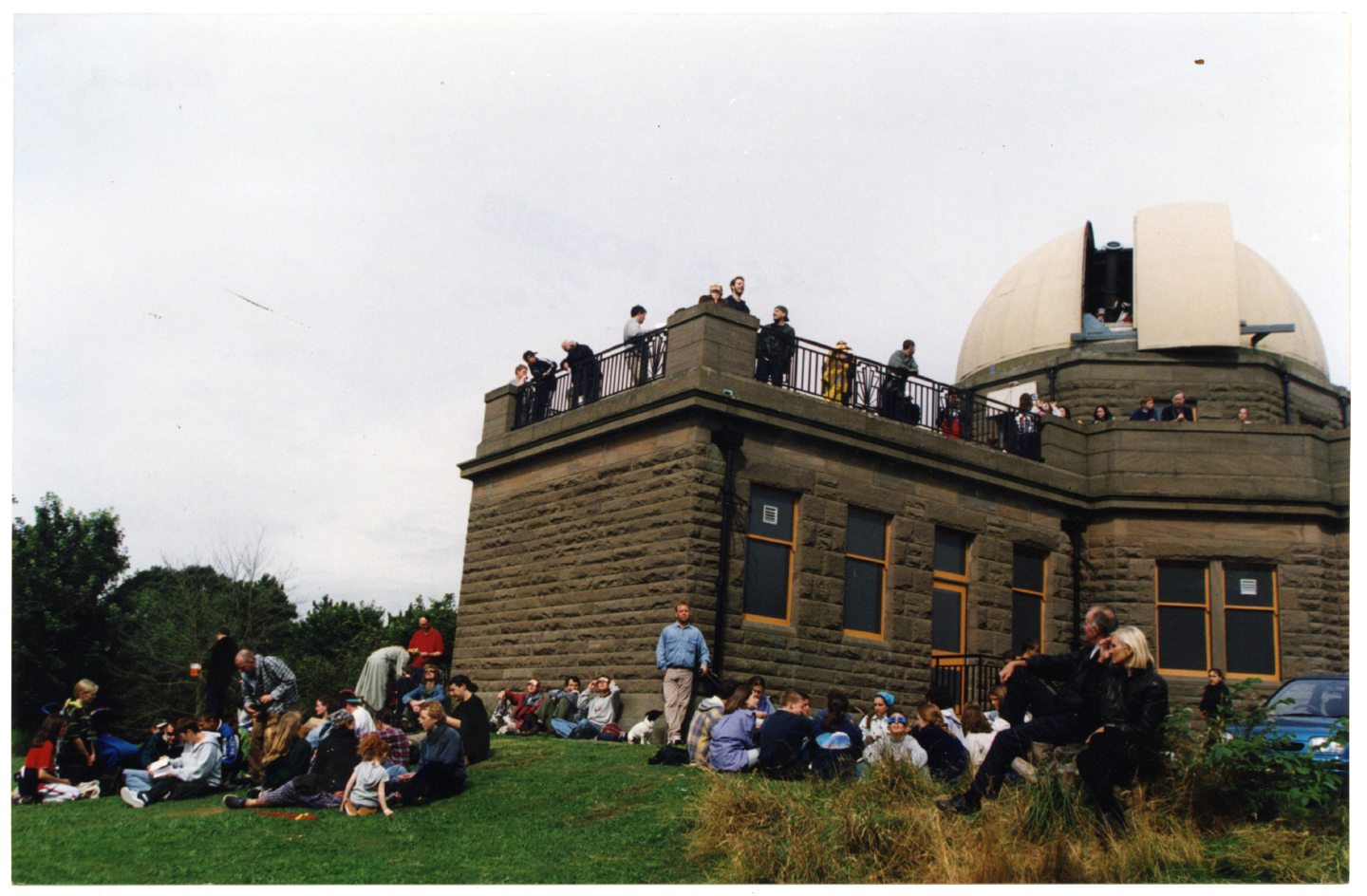

Below a large crowd utilise all the space the Observatory offers as they eagerly await an eclipse that was due in August 1999.

The observatory hopes to reopen soon with restrictions easing and we are sure it has many more years of inspiring Dundonians young and old to come.