It’s a sports festival that brings families and even whole communities together in a spirit of celebration.

Who can forget the scenes of joy that followed the Olympic open-top bus parades around Scotland, following the gold rush and magical medal trails at the London Games in 2012?

Later this month, and despite the Covid pandemic that forced the proceedings to be delayed for a year, Tokyo will stage the global exhibition of games without frontiers on the athletics track, in the pool, the velodrome and on the tennis courts, football pitches, golf course and a range of other venues.

Scotland will be well represented in Japan and while we will have to wait to see whether any of the participants can achieve podium success, they should derive inspiration from knowing they are following in illustrious footsteps.

But that raises a question that we thought might pique your interest. Who do you think deserves the mantle of Scotland’s greatest Olympian?

We have drawn up a list of 10 remarkable competitors – one of whom has flourished in the Paralympics – and their feats stretch back almost 100 years.

But which is the cream of the crop?

Neil Fachie (Paralympic cycling)

This redoubtable fellow was born in Aberdeen in 1984 and, despite having a congenital eye condition – retinitis pigmentosa – has flung himself into both his academic and sporting pursuits with a vengeance.

Fachie, who originally took part as a sprinter in the 2008 Paralympics in Beijing, switched to the cycling domain thereafter and his strength, technical expertise and commitment to training quickly impressed the British coaches.

In 2009, he entered the para-cycling world championships with Barney Storey as his pilot and the dynamic duo surged to the gold in both the kilo and sprint, setting a new world record in the former discipline.

That was merely the hors d’oeuvre to the main course that Fachie served up in front of his home fans, friends and family at the London Games when he struck gold again in the Paralympics in the men’s 1km time trial.

The smile on his face at the finish was unforgettable; as was the joy when a gold postbox was unveiled in his honour in Aberdeen.

It was a special moment for a man who has excelled on the Commonwealth and international stage, as well as gaining two silvers at the Paralympics in Rio in 2016, even as he has become a master motivator in his homeland.

Katherine Grainger (rowing)

It was one of the first occasions when many of us started delving into the minutiae of Olympic rowing.

And, while the exploits of Steve Redgrave were the catalyst for a plethora of people’s conversions to the sport when he said to his colleague Matthew Pinsent “Let’s crush some dreams”, prior to making Olympic history in Sydney in 2000, the emergence of another British competitor on that grand Australian odyssey became one of Scottish sport’s greatest stories.

Katherine Jane Grainger, the relentlessly single-minded and endlessly tenacious competitor tried, tried, tried and tried again to strike gold in her sphere – and finally succeeded in front of her home audience during the London Games at the start of August in 2012.

There had been silvers in Sydney, in Athens, in Beijing and other competitors might have felt they were destined to settle for second in perpetuity.

But Grainger, born in Glasgow but with family in Aberdeen, was as uninterested in the possibility of defeat as Queen Victoria – and she finally attained the cherished gold medal in front of an ecstatic home throng.

And her palette of emotions – exhilaration, exhaustion, elation – as she waited to receive her long-awaited prize was priceless and encompassed the sheer joy that surrounded the Games.

Chris Hoy (cycling)

Ever since I started watching Chris Hoy train in rain, wind or snow at Meadowbank in Edinburgh or at the velodrome in Manchester, it was evident this tenacious and beetle-browed Scot possessed the philosophy that challenges were there to be savoured and enjoyed.

The statistics speak for themselves: the Edinburgh man was a world champion 11 times and an Olympic gold medallist on half-a-dozen occasions.

Three of these successes came at the 2008 Games in Beijing, where Hoy became Scotland’s most successful Olympian, the first British athlete to win a hat-trick of gold medals in a single Olympics since Henry Taylor in 1908.

But it wasn’t simply the barnstorming fashion in which he pocketed a further brace of gold medals – in the keirin and the team sprint – at the 2012 Olympics in London, which were sufficiently memorable to stir the blood.

Instead, it was the astonishing sangfroid he demonstrated as he watched his opponents set new personal bests during the men’s individual sprint event in China.

Other performers might have been daunted by the quality of those who had gone before him, but not this customer.

Cometh the hour, he powered out of the blocks and blew away everything that had happened in the previous hour. It was magical and showed the qualities of a truly great competitor.

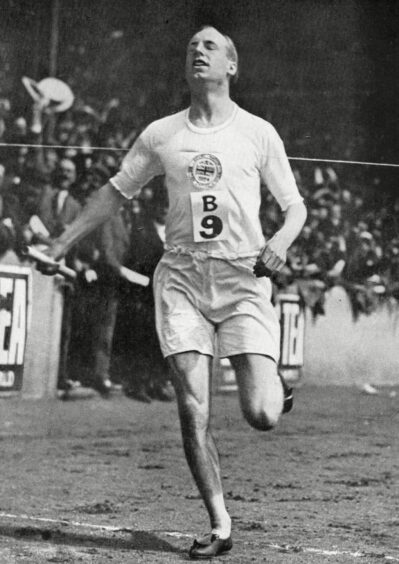

Eric Liddell (athletics)

There haven’t been many sports personalities whose exploits have been transformed into an Oscar-winning film but, then again, Eric Liddell, the Flying Scotsman, wasn’t like most ordinary performers.

His story, which provided the inspiration for Chariots of Fire, spoke of how he lived and died in another time, another place: one where he regarded his strong religious faith as being more important than any baubles or trinkets.

Liddell, who was born in Tianjin in China to Scottish missionary parents, was a supremely talented athlete, who also represented his country at rugby, and was the favourite to collect at least one gold medal when he and the British team travelled to the Paris Games in 1924.

However, after glancing at the schedules, he refused to run in the heats for the 100 metres because they were being held on a Sunday.

Instead, he competed in the 400 metres, which were staged on a weekday, and was sufficiently gifted that he soared to victory against his rivals.

In other circumstances, considering his abilities, Liddell would surely have secured many more honours, but his attitude was that sport was simply a relaxation, a distraction from the bigger calling of serving others.

That was why he returned to China in 1925 to serve as a missionary teacher and, apart from two furloughs in Scotland, he remained in the Far East until his death in a Japanese civilian internment camp, aged just 43, in 1945.

He was a modest, self-effacing figure. But his name is etched in history.

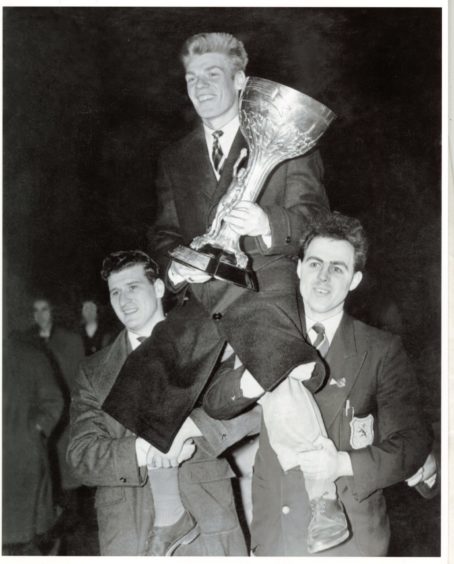

Dick McTaggart (boxing)

This is the fellow who is widely regarded as Dundee’s greatest Olympian and it’s hard to quibble with that assertion when you consider the imperious fashion in which he stamped his imprint on the sport in the 1950s and 1960s.

McTaggart, who is now 85, remains the only Scottish boxer to win Olympic gold, at the 1956 Games in Melbourne, and has been acclaimed as the finest amateur boxer Britain has ever produced.

The legendary BBC commentator Harry Carpenter described McTaggart as “the greatest amateur I ever saw” and yet, though there were offers, the Scot was never tempted to turn professional despite pressure from promoters.

On the contrary, the champion at the 1956 Olympics and 1958 Commonwealth Games, as well as the bronze medallist at the 1960 Games in Rome, was happier nurturing future generations in the fistic arts.

In retirement, McTaggart worked as a boxing coach and prepared the Scottish team for the 1990 Commonwealth Games, coaxing and cajoling youngsters and putting them through their paces.

In 2002, he was inducted into the Scottish Sports Hall of Fame, but there’s no point speculating how he might have fared in the pro ranks. He was happy to commit himself to other things 60 years ago and has never regretted it.

Andy Murray (tennis)

He’s the man who had boldly gone where no Scot had ever gone before, climbing to the No 1 ranking in world tennis and creating headlines all over the globe with a series of unprecedented achievements.

The Dunblane maestro made his major breakthrough in 2012 by defeating Novak Djokovic to win the US Open in New York.

With this title, he became the first British Grand Slam singles champion since Virginia Wade in 1977 and the first male winner since Fred Perry in 1936.

A month earlier, he had surged to a gold medal with a demolition of Roger Federer at the London Olympics – and he followed that up by triumphing at Wimbledon twice, in 2013 and 2016, and subsequently becoming the only player to defend his Olympic crown in Rio.

Despite serious injury, and the insertion of a steel plate in his hip that has restricted his time on court in recent years, Murray is still chasing fresh conquests and he will be in the Olympic mix again in Tokyo.

Rodney Pattisson (sailing)

Some people have never been interested in messing about in boats. They are sailors with a passion for the sea and the whiff of competition in their nostrils.

Pattisson, born in Campbeltown where his father was posted as an airman during the Second World War, might not be a household name with the younger generation but his achievements at Olympic level are legendary.

This resilient character was a double Olympic gold medallist on the water at the 1968 and 1972 Games in Mexico City and Munich and both successes came in the Flying Dutchman class, where he was in his element.

He also won a silver medal at the 1976 Games in Montreal in the same class to become Great Britain’s most successful Olympic yachtsman of the period.

Pattisson then co-skippered the Victory 83, the Peter de Savary entry in the America’s Cup in 1983, before being inducted into the Sailing Hall of Fame.

Heather Stanning (rowing)

Here is another stellar performer on the water, and somebody else who had bigger issues to deal with when she wasn’t involved in sport.

In tandem with her colleague Helen Glover, Stanning secured gold in the women’s pairs at both London 2012 and Rio 2016, with the duo enjoying an unbeaten streak in their domain that dated all the way back to 2011.

Yet, while the Scot was exceptional at the Games, she was committed to a career in the military and returned to action after the London Olympics, completing a tour of duty in Afghanistan with the Royal Artillery in 2013.

Stanning’s mother, Mary, was understandably breathless with delight after watching her daughter’s gold medal win from the lakeside at Eton Dorney.

She had travelled from her home in Lossiemouth, best known for its RAF base and in close proximity to Stanning’s former school, Gordonstoun.

And the golden postbox that stood proudly in the Moray town testified to Stanning’s momentous feat.

Allan Wells (athletics)

He came from the same city as James Bond star Sean Connery and Wells was the man with the golden run in Moscow in 1980.

The Scottish sprinter was among those who came under pressure from Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher to boycott the Games, following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan just a few months earlier. And the absence of US athletes at the Olympics clearly created an opening for the rest of the field.

Yet, regardless of the circumstances, Wells famously rose to the challenge in the 100m final and, even as his wife Margot conducted a shrieking commentary next to David Coleman, her husband roared out of the blocks and narrowly pipped his opponents to the spoils.

He later added a silver in the 200m and while his achievements have been tainted by (unproven) allegations of drug abuse, Wells remains the only man from his country to have broken the tape in the blue riband event.

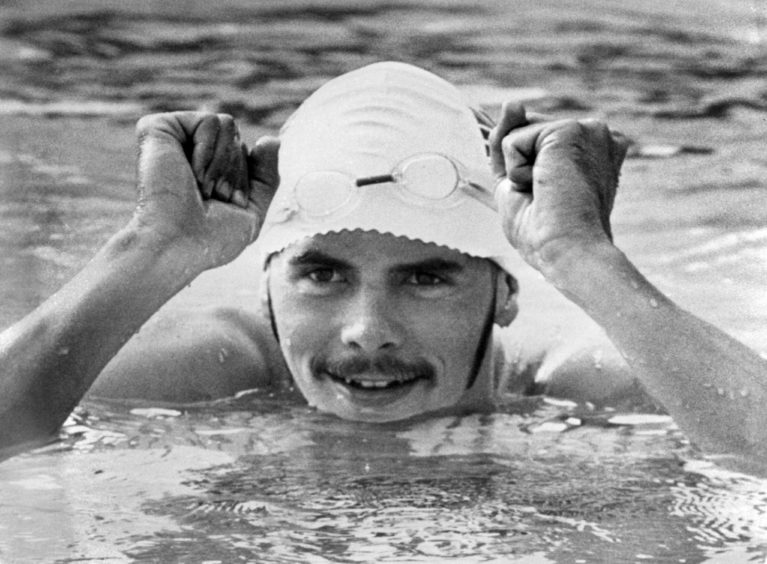

David Wilkie (swimming)

He developed his talents in a world long before there was National Lottery funding or elite athlete training schemes.

But when Wilkie won the 200m breaststroke final at the 1976 Montreal Olympics, the Scot created history by becoming the first male British swimmer to take gold for 68 years.

The Edinburgh competitor was up against a string of American and Australian powerhouses in the sport, but was undaunted by the prospect and all the hours spent in the pool on cold, dank winter mornings proved their worth.

After training at Warrender Baths Swimming Club, the youngster made his Olympic debut at the 1972 Games, where he transcended a lowly world ranking to claim a shock silver in the 200m breaststroke.

That success was the catalyst for him being offered a scholarship at the University of Miami and he subsequently won the world 200m in 1973 and 1975 as the prelude to his unforgettable Olympic triumph.

There was no arguing with the quality of his display when it mattered: the redoubtable Wilkie smashed the world record by more than three seconds and also picked up a silver in the 100m breaststroke at the same Games.