Ladybank Golf Club historian Bob Drummond reveals the fascinating tale of an unsung Scottish hero to Michael Alexander

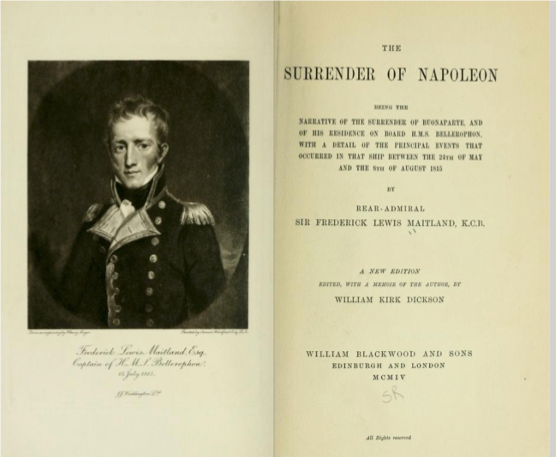

Just over 180 years ago there died off Bombay a relatively unsung Scottish naval hero, Rankeilour-born Captain Frederick Lewis Maitland, who accepted the surrender of Napoleon after Waterloo on the deck of his ship, HMS Bellerephon.

He was born in 1777 and after an education in the High School of Edinburgh (later Royal High) and doubtless assisted by his aristocratic Maitland connections, Maitland joined the Navy as Midshipman, quickly rising to the rank of Post-Captain in 1801.

There followed a distinguished career in battle against the French, including the taking of many prizes and leading a particularly daring action in Muros Bay in 1805, heroism which led to his receiving the thanks of the City of London, the freedom of Cork, and a sword from the Patriotic Fund.

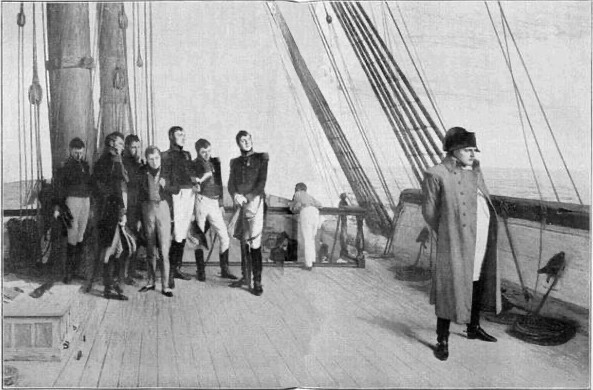

After captaining a succession of ships, Maitland was appointed to HMS Bellerephon (nicknamed Billy Ruffian) and was ordered to sit off the west coast of France in 1815.

Trapped between Prussian/Royalist forces to the east, and the blockading British fleet to the west, the defeated Napoleon threw himself on the mercy of British justice and surrendered to Maitland.

The captain placed his own cabin at Napoleon’s disposal and dined with him in the evenings, conversing in French, during the voyage back to Plymouth.

At dinner, Napoleon restricted himself to a couple of glasses of claret.

Before his departure to St Helena, an appreciative Napoleon pressed gifts on the courteous Captain Maitland, namely a crystal tumbler engraved with a J(osephine), a gift for Maitland’s wife of cases of claret (subsequently confiscated by Customs!), and, according to family lore, a live cow which passed its days chewing the cud at Lindores, Fife.

Maitland had purchased the Lindores estate from his mother and in 1820 erected the white house which stands by the loch, utilising his £16,000 prize-money accrued.

Maitland subsequently wrote his riveting memoir of the event in “The Surrender of Napoleon”, an account encouraged to publication in 1826 by Sir Walter Scott.

In 1832 Maitland was appointed Admiral-Superintendent of Portsmouth Dockyard before being sent out to India where he died at sea at the age of 62 on November 30 1839.

A central figure in the story was Maitland’s wife, Limerick-born Catherine Conner, whose miniature portrait hung in the captain’s cabin, and was greatly admired by Napoleon.

“Qui est cette jeune personne?”. “My wife,” replied Maitland. “Ah, elle est très jeune et très jolie.” Three weeks later, off Plymouth, Catherine was rowed out to speak with her husband from her gig and Napoleon invited her on deck, but Catherine shook her head – it was not allowed.

Napoleon said to her, “Milord Keith (the Plymouth Admiral) est un peu trop sévère, n’est-ce pas, Madame?”

He continued to Maitland, “Ma foi, le portrait ne la flatte pas; elle est encore plus jolie que lui”.

On arrival at Plymouth, Napoleon insisted on giving Captain Maitland some cases of claret as his gift for Lady Maitland, at whose portrait Napoleon had been gazing in his cabin for three weeks.

Captain Maitland rowed the wine ashore in his gig to leave with his wife at her lodgings, but when his boat beached on the Plymouth shingle, Customs stepped forward and confiscated the lot, leaving a fuming Maitland!

Later, Captain Maitland received a bad press from some Bonaparte supporters who alleged that Maitland had promised him a good reception in Britain and had therefore tricked him into surrender.

In his memoir, Maitland is at pains to point out that he always stressed to Napoleon that he could make no promises as to what would be the outcome of his delivery to the Government, and on parting, Napoleon thanked him.

“I have requested to see you, captain,” said he, “to return you my thanks for your kindness and attention to me whilst I have been on board the Bellerophon, and likewise to beg you will convey them to the officers and ship’s company you command.

“My reception in England has been very different from what I expected; but it gives me much satisfaction to assure you, that I feel your conduct to me throughout has been that of a gentleman and a man of honour.”

In fact, had Napoleon remained in France, he would have been subjected to a humiliating execution so he had no choice but to throw himself on Britain’s mercy.

Napoleon hoped to form a relationship with the Prince Regent and optimistically expected a quiet estate where he could see out his days.

The British Government however took the view that Napoleon had caused so much bloodshed throughout Europe that distant banishment to the inhospitable St Helena was the only civilised answer.

Napoleon had great personal courtesy and charmed the Bellerephon crew during his stay on-board. Lord Keith, Admiral of the English Channel, was also fascinated by Napoleon’s conversation, and speaking of his wish for an interview with the Prince Regent, Keith said: “If he had obtained an interview with his Royal Highness, in half an hour they would have been the best friends in England.” Maitland subsequently learned that had Napoleon met up with the Prince Regent, Napoleon would have requested Maitland’s elevation to the rank of Rear-Admiral.

Lady Maitland accompanied her husband out to India and on his death, she returned to Lindores where she lived until her own demise in 1865.