Michael Alexander hears the fascinating tale of an Arctic Inuit called Olnick who became a “minor local celebrity” in 19th century Dundee after returning to the city to live with whalers.

He was the indigenous and “feared” tribal chief from the frozen wastes of the high Arctic who persuaded Dundee whalers to take him back to the city with them so that he could see where they came from.

Now the remarkable story of a 19th century eskimo called Olnick is being resurrected by a North America-based historical climatologist who wants to “reconnect” the Inuit populations of northern Canada with their 19th century heritage in Dundee.

North East England-raised Dr Matthew Ayre was researching the logbooks of British Arctic whaling ships when he discovered a “number of amazing cultural links” between the Inuits of Baffin Island and Dundee.

He was particularly fascinated by the story of Olnick who was well known to Dundee whalers and who eventually agreed to let him accompany them home.

“Olnick became a bit of a minor celebrity in Dundee,” Matthew told The Courier.

“He had an audience with the Prince of Wales, goes back to Baffin and continues to lead a group of 40 people on an island next to a fjord where various wrecked whaling ships ended up.

“He was known for salvaging wrecks. It was reported he salvaged the wreck of the Ravenscraig out of Kirkcaldy.

“But when he died in 1900, his son in law took over and the group moved south. That explains why when the Dundee whaling ship Nova Zembla wrecks two years later nobody salvages it.”

Matthew came across a first hand account of Olnick’s funeral, attended by Dundee whalers, through the British Newspaper Archive.

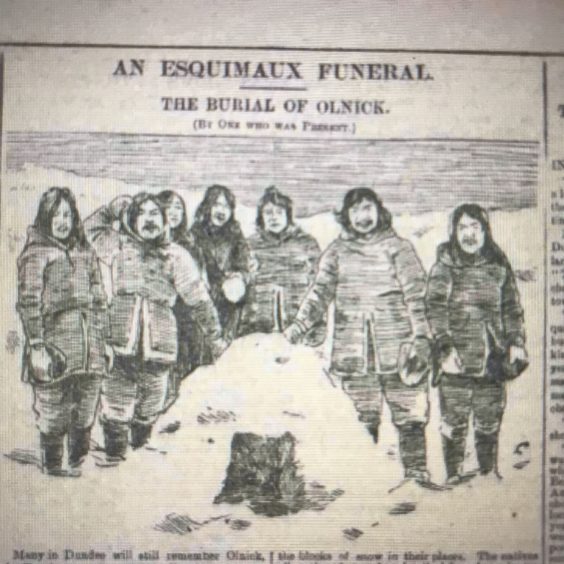

A Dundee Evening Telegraph report of Monday December 17 1900, under the headline ‘An Esquimaux Funeral – The Burial of Olnick’, went into detail about the “particulars” of the inuit funeral. The details were provided by “one who was present” with photographs supplied by F.Gillies of Broughty Ferry who had been in the area aboard the Dundee whaling ship Diana.

“Olnick was rolling about on the ground and moaning continually,” Mr Gillies said.

“I saw that the end of Olnick was not far off. I then returned to the ship, and after breakfast the following morning I went ashore, taking my camera along with me.

“I saw a number of natives on the side of hill, busily working. I went up and found them preparing a snow grave for Olnick, who had died after I left the previous evening.

“Alter lacing him into a large seal-skin, the natives carried him to the top of a ridge, and, fastening the dogs which belonged to the dead man to his feet, made them drag him to the burial place, a distance of about half a mile.

“The men cut out a grave in the soft snow with largo bone knives, and laid Olnick in it, and along with him his gun, pipe, tobacco, matches, and some blubber for food.

“The natives all gathered round and talked for a few minutes each, and at the end of each speech all joined in a kind chant, recited in low monotone. When they had finished they formed in line, with the three who had dug the grave at the front. The procession then marched, or rather floundered, down the hill.”

After another ceremony with more chanting, Mr Gillies returned to his ship and reflected on the life of a man who was “feared throughout the length of the Davis Straits”.

During his lifetime Olnick had shot three men, and there still existed “Cumberland Gulf man” who had sworn he would shoot Olnick at sight tor having shot his brother a number of years previous.

Mr Gillies added: “While making mv way back to the Diana I mentally compared the end of Olnick with that of people at home.

“He will sleep comfortably in his snow grave at Dexterity till spring comes round again and the snow melts, when the dogs will make a meal of him – such is the fate the Esquimaux.”

Today whaling is regarded as socially, morally and ethically unacceptable with many of the giant seaborne mammals on the verge of extinction.

But between the 18th and 20th centuries, Dundee whalers were at the forefront of a lucrative industry that yielded tons of valuable oil to lubricate the industrial revolution. Bones were also used to form the supports of corsets and petticoats.

Over exploitation of bowhead whales around Svalbard saw whaling fleets move to the Davis Strait then up into Baffin Bay.

Dundee’s presence in the whaling industry began in 1753 starting with the ship ‘Dundee’.

But by the mid-19th century whaling was in decline with only Scottish ports –particularly Dundee – persisting until the start of the First World War.

* In the Courier Weekend magazine of May 30, we hear how a single entry in a 118-year-old Arctic whaling ship’s logbook led researchers to the perilous waters of the Canadian Arctic and the rediscovery of a long-lost Dundee ship wreck that was never salvaged following Olnick’s death.