Are the roots of modern day racism rooted in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade and does Scotland need to face up to its slave-owning role in the British Empire to move forward? Michael Alexander seeks the views of Dundee University experts.

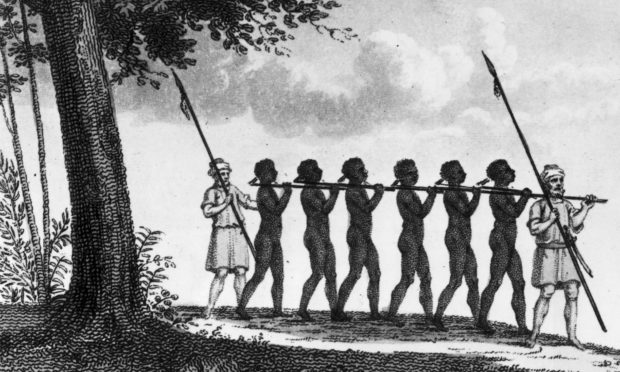

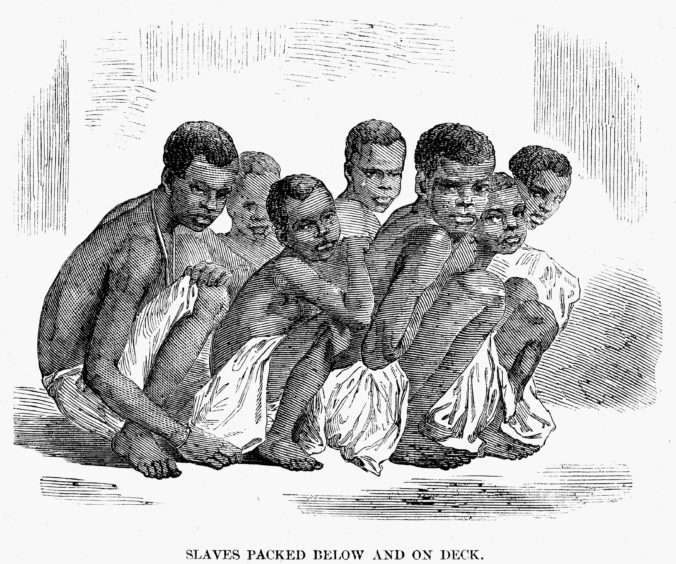

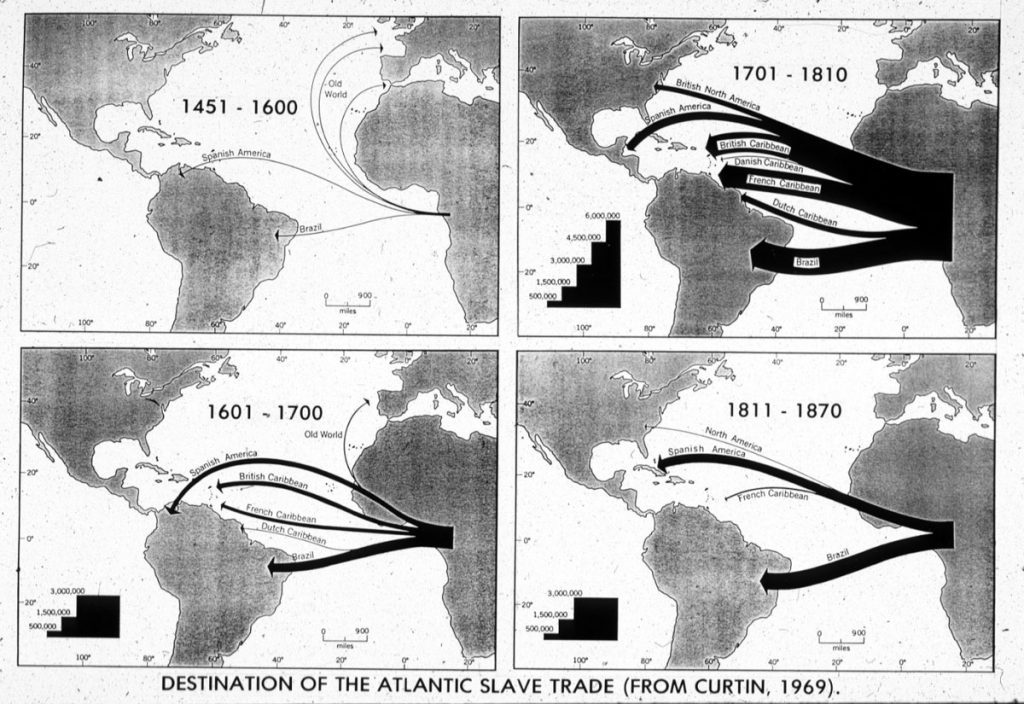

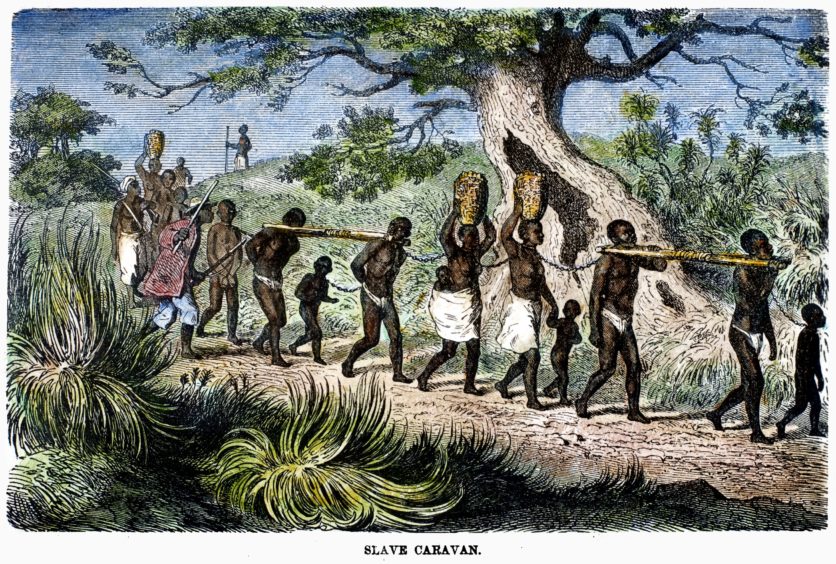

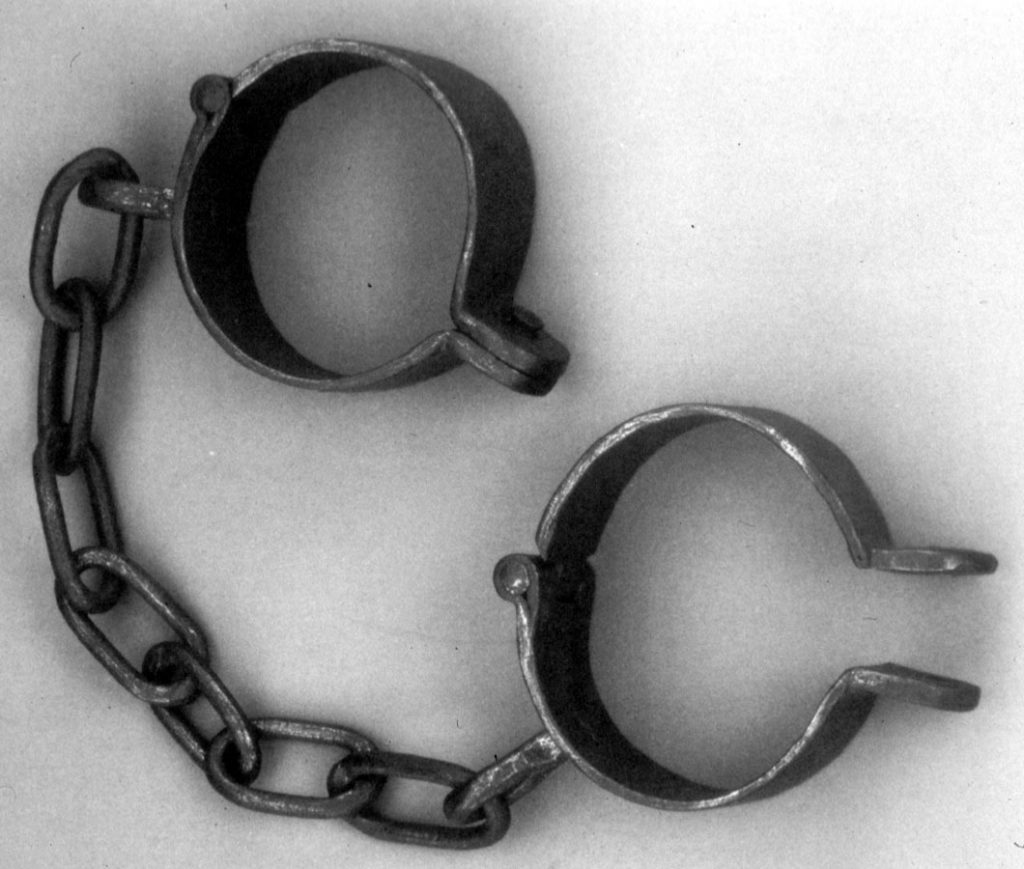

For well over 300 years European countries forced Africans onto slave ships and cruelly transported them across the Atlantic Ocean in iron chains.

Whilst Portugal was the first nation to engage in the Transatlantic Slave Trade from the late 1400s, historians have calculated that British ships carried 3.4 million or more enslaved Africans to the Americas between 1562 and the abolition of the Slave Trade in 1807.

The recent Black Lives Matters protests have shone a light on the roles – and the statues – of slave traders like Edward Colston in Bristol.

But Courier Country also had uncomfortable connections with the slave trade.

In 2016, the BBC Radio Scotland documentary “It Wisnae Us’ highlighted four ships from Montrose directly involved in the slave trade while a further 30 Montrose ships were involved in tobacco trade with Virginia which was very much dependent on slave labour.

The Rossie Estate was an example of wealth founded on slavery, whilst a document buried in the National Library of Scotland archives for centuries – a ‘Narrative of an Unfortunate Voyage to the Coast of Africa’, written by Arbroath sailor Thomas Smith and published locally in 1813 – described a dramatic rebellion on board a slave ship. Dundee’s linen industry also had strong connections.

The University College London Legacies of British Slave-ownership database lists at least 17 Perthshire and 21 Fife former slaveholders and dependents filing compensation claims for the loss of revenue when slavery ended in the then British Caribbean islands.

Dr Michael Morris, senior lecturer in English and history within the School of humanities at Dundee University, did his PhD on a cultural history of Scottish connections with the Caribbean between 1740-1838.

He’s been researching how Caribbean slavery helped shape Scotland’s economic, social and cultural development and says there’s no doubt the findings are “troubling”.

“Research over the last 20 years or so has revealed Scotland’s profound involvement in Atlantic slavery,” he said.

“This has been troubling because we are steeped in the sense of Britain as a liberal empire with Scots as its canniest organisers- as engineers, doctors, and soldiers.

“The picture gets even more confused as people who should know better make false equivalences between, say, cleared Highlanders, or Glasgow slum-dwellers as being much the same thing as enslaved chattel.”

Dr Morris says the re-evaluation has largely focused on Glasgow but it’s “increasingly clear” that slavery was a shaping factor across every part of Scotland.

The linen mills around the North East of Scotland, for example, exported ‘slave cloth’ to the Americas.

“In Dundee,” he explained, “we have the Langlands family who at the ending of slavery claimed compensation for their loss of ‘property’- meaning enslaved people on their plantations in Jamaica.

“And of course John Wedderburn returned to near Dundee from Jamaica with a young man named Joseph Knight.

“Knight wanted to marry a Dundee woman named Ann Thompson but Wedderburn disapproved of the relationship.

“It was Knight’s refusal to submit which eventually led to a landmark legal case in 1778 in which Knight won his freedom and he is credited with establishing a legal precedent that slavery was not permitted on Scottish soil, even while it raged in the colonies.”

Dr Morris said there’s no doubt the origins of modern racism are profoundly shaped by how empires justify themselves.

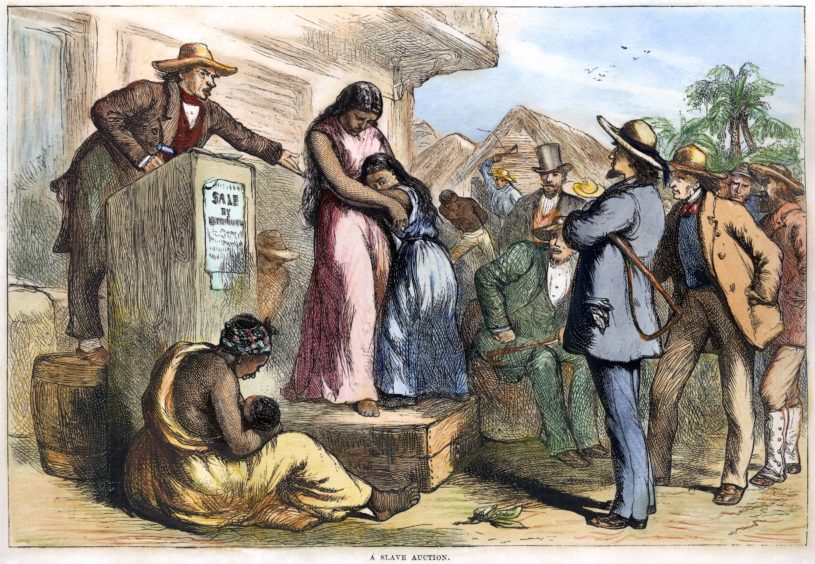

Empire builders see it as necessary to forge a hierarchy of humans in which some were born to rule and others born to toil.

Scottish thinkers helped to construct ideologies of racial inferiority: David Hume, Robert Knox, Thomas Carlyle.

At its most insidious, Africans were depicted as simple creatures requiring to be led like children.

At its most vulgar, Africans were seen as brutes, closer to the animals, requiring to be treated with force.

“We see this still at work today in the shocking video of George Floyd in Minneapolis,” added Dr Morris.

“We must condemn this strongly and send full solidarity to those protesting for justice.

“But, perhaps more importantly, we should take this time to look ourselves squarely in the mirror.

“Let’s ask ourselves what happened to Sheku Bayoh on the streets of Kirkcaldy, and let’s not tell ourselves that this is just an American problem.”

Prior to arriving at Dundee University in 2011, human geography lecturer Dr Susan Mains taught for nearly 10 years at the University of the West Indies-Mona in Kingston, Jamaica.

It was a “very special experience” that inspired her to be more reflective and critical of her own assumptions about place, about Scottish identities and the role of Scotland during colonialism.

While there, she became increasingly interested in understanding the impacts of colonialism, alongside the contradictions of living in a place that is promoted as a popular tourist destination while simultaneously being a country that has had significant levels of emigration.

From 1707 to 1962 Jamaica was a British colony (from 1655 it was claimed as an English colony), and this had ramifications in terms of how the economy was structured and how race was utilised to reinforce social hierarchies with longstanding consequences.

“Talking with colleagues and friends in Kingston it struck me that many people in Jamaica were familiar with Scottish history and the presence of Scottish migrants in the Caribbean, and yet I had been taught very little about the Caribbean or Scotland’s role in the slave trade when I was growing up,” she said.

“Although there is documentation of a Scottish presence in Jamaica—specifically in relation to Scottish-owned plantations during slavery—this was largely left out of the Scottish national curriculum and discussions about empire until fairly recently.”

While living in Jamaica, Dr Mains came across a set of photographs by Valentine & Sons of Dundee. These had been taken in 1891 and were presented at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago.

“The striking images showed a diverse range of rural and urban landscapes compiled in the hope of promoting the island as a place to visit and to invest in, the latter seen as particularly important following the decline of the plantation economy.

After moving to Dundee a few years ago, she found out that the remaining Valentine & Sons images were held in the University of St Andrews Photography Special Collections.

While speaking with archivists there in relation to putting on an exhibition in the Lamb Gallery at Dundee University, she learned about the Scottish photographer, Stephen McLaren and his recent photo series—“Jamaica-A Sweet Forgetting” – where he documents images of locations in Jamaica that were once owned by Scottish planters and then juxtaposes them alongside Scottish locations that benefited from the profits of those plantations.

One nearby example, she said, was Ballendean House in Perthshire, previously owned by John Wedderburn who became wealthy from sugar plantations in Jamaica.

Bringing past and present together and contacting the Jamaican photographer, Varun Baker, who explored personal experiences of mobility and disability in his photo essay “Journey” set in the city spaces of Kingston, she put on the exhibition “Moving Jamaica: Scottish-Caribbean Connections and Local-Global Journeys” from October 2018 to January 2019 – and it will be going on tour to the St Andrews Preservation Trust once Covid-19 restrictions have been lifted – possibly in late July.

Dr Mains said there’s no doubt it’s important for Scotland to investigate and discuss her role in the slave trade in order to have a fuller, more inclusive and critical understanding of our identities.

“Colonialism and the slave trade established and set the framework for the ways in which we conceptualise, address and discuss race and economics,” she added, “and so in that sense, the way in which black identities have been represented, framed and policed, has emerged from a set of social relations that are fundamentally unequal.

“Efforts to challenge those inequalities have been ongoing, and require even more urgent attention. We are all responsible for educating ourselves about inequalities and we need to take decisive steps to address them.

“The key responsibility now lies with those in power and who benefit from being in privileged positions—individually and as part of institutions—to learn, reach out and actively take that privilege to task, while actively challenging racism.”