Three hundred years after the birth of the ‘Young Pretender’ Bonnie Prince Charlie, Michael Alexander examines the world’s fascination with the “doomed prince” and discovers the many myths that have grown up around the Jacobite cause over the centuries.

Amongst the fascinating array of artefacts on display in the Scottish galleries of the National Museum of Scotland, the museum’s permanent collection of Jacobite material includes a silver travelling canteen made by Edinburgh goldsmith and Jacobite Ebenezer Oliphant.

Made in 1741, there’s a theory it was sent out to Rome – where Britain’s royal House of Stuart was exiled – for Prince Charles Edward Stuart’s 21st birthday.

As the Italian-born, half-Polish grandson of the deposed Catholic King James VII of Scotland and II of England, it was something that the ‘Young Pretender’, also known as Bonnie Prince Charlie, brought back to Britain when he led the ill-fated Jacobite Risings of 1745 to overthrow King George II.

The museum, which also owns a sword and a targe associated with the prince, bought the canteen using Heritage Lottery funding and following a public appeal.

But 300-years after his birth in Rome on December 31, 1720, what is it about Bonnie Prince Charlie that still captures the imagination?

What might have been

“He’s obviously always been of interest in the way that we in Scotland like to celebrate failures,” says David Forsyth, Principal Curator, Renaissance and Early Modern History at the National Museum of Scotland.

“But I think it’s more than that. I suppose it’s the whole ‘what might have been’: that they, the Jacobites, were not successful.

“Obviously you’ve got Mary Queen of Scots as well. It’s the view of some that she too was unsuccessful.

“But were they really unsuccessful? The very fact their legacies live on to this day show how powerful they are.

“There’s a lot of myths that have grown up against these people.

“But it’s a pretty powerful reality.”

The Outlander effect

When the National Museum of Scotland staged its Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites exhibition in 2017, Outlander writer Diana Gabaldon asked to go behind the scenes to help research her work.

It was a move that impressed Mr Forsyth, who adds: “As a writer of historical fiction she does her research incredibly well and as a driver for tourism and interest in Scottish history it would be churlish to think that Outlander has done nothing but good.”

The so-called ‘Outlander effect’ is certainly evident, says Visit Scotland.

“Bonnie Prince Charlie is one of Scotland’s most enduring historical figures,” a Visit Scotland spokesperson says, “and it was Sir Walter Scott, long been considered the father of the modern Scottish tourism industry, who ignited an interest in Scotland as a visitor destination with his first historical novel Waverley, set during the Jacobite rising.

“The popularity of the hit book and television series Outlander, and its romantic interpretation of the Jacobites, has also helped maintain interest in the ‘Young Pretender’ and seen a boom in visitor numbers to Jacobean-related attractions over the past decade.”

With season six of the TV series set to premiere and 2021 also marking the 250th anniversary of Sir Walter Scott’s birth, Visit Scotland expects interest in Bonnie Prince Charlie and this time period to only grow.

But while there’s no getting away from the worldwide influence of the modern day TV show and how its fictional storyline resonates with visitors, the museum also hopes its own exhibitions show “there’s no such thing as the truth in history”.

Shattering the myths

It’s all nuance and opinion. What the museum tries to show is the “proper context” of how the prince made his attempt to regain his throne and to shatter some of the commonly held myths that have infiltrated history.

“That’s one of the first myths that’s grown up about the Jacobite era,” says David.

“Bonnie Prince Charlie came not to take the throne for himself but for his dad James VIII of Scotland and III of England.

“Another myth around it surrounds the Stuart dynasty. The court was obviously Catholic, but the bulk of their supporters were Protestants.

“You had the Episcopalians from the classic Angus and Aberdeenshire area up into the Highlands.

“It wasn’t in any sense a ‘Catholic versus Protestant’ thing.

“Another one of the greatest myths is the English/Scottish thing.

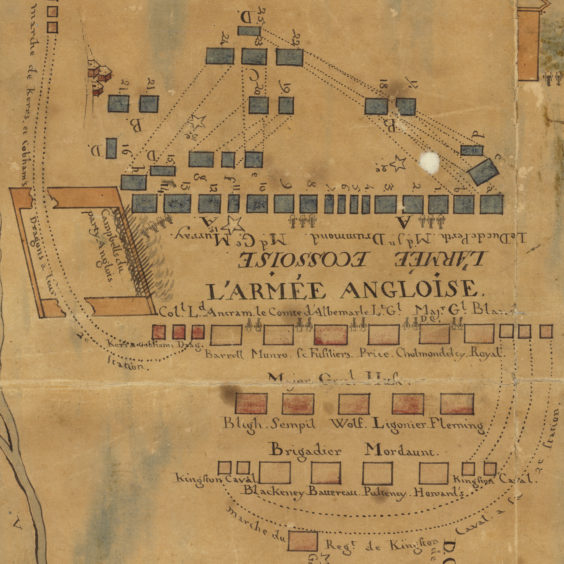

“In actual fact, the Jacobite army was an international army. It obviously had Scots – Highlanders and Lowlanders.

“The government army had Highlanders and Lowlanders and Englishmen.

“And of course, you get that resonance with Europe, there was the regiment the Royal-Ecossais – the French regiment – and there were Irish units in the Jacobite army too.

“So although we have that famous David Morier painting of Culloden showing the ordered ranks of the Redcoats with their muskets and drills and the wild bedraggled Highlander with their targes, the Jacobite army was organised on the rules of engagement of a standing European force.

“There was a lot of musket fire from the Jacobite side over into the British army.

“The Stuarts saw themselves very much as a European dynasty. So to understand the Jacobites is to understand that this was not just a Scottish or British phenomenon – the Jacobites were a European phenomenon.

“That’s something that’s very topical to this day!”

Brutal aftermath

Of course, when the Jacobites were catastrophically defeated at Culloden on April 16, 1746, it marked not just the final defeat of Charles Edward Stuart and his followers but also marked the final destruction of the centuries-old Gaelic Highland way-of-life.

In the aftermath of Culloden, contemporary accounts tell how wounded Jacobite supporters were brutally executed on the battlefield by British army soldiers, women were raped and killed and children slaughtered on the streets of Inverness, while prisoners shipped to London either died as a result of appalling conditions, were executed or were transported to the West Indies to be sold as slaves.

The actions resulted in the Duke of Cumberland, who led victorious Hanoverian troops at Culloden, being nicknamed the Butcher, while the tale of Bonnie Prince Charlie’s escape “over the sea to Skye” and on to exile in France is now legendary and has inspired both song and story.

Yet the Jacobite dream continued to burn. Another interesting object held by the National Museum of Scotland and linked to the prince’s birthday is a beautifully enamelled wine glass, possibly used by Robert Burns when he attended a dinner organised by the Jacobite supporting Steuart Society (correct spelling Steuart) on December 31, 1787.

What’s interesting is that when that dinner was held, the exiled Charles Edward Stuart was still alive. He died exactly a month later aged 67.

Culloden battlefield tourism

Katey Boal, National Trust for Scotland engagement manager at Culloden Battlefield, says there’s undoubtedly “something about the romance” of the story of the “doomed prince” that really appeals to people.

“She lays this at the door of Victorians like Sir Walter Scott who wrote songs.

But she is certain the brutal aftermath of Culloden, which many government supporters were also uncomfortable with, also influenced how the prince and his supporters are perceived.

“Bonnie Prince Charlie was a tall, attractive man and he was very charismatic,” she says.

“He was definitely the sort of person who could work a room. He was able to capitalise on that.

“There were stories of how clan chiefs were told not to go and speak to him because when they speak to him they’ll follow his cause. He’s that sort of person.

“He has his character flaws as well. But he’s definitely a charmer. He’s definitely somebody who was able to persuade.

“He’s also a young man. He was 25 at Culloden which is incredibly young.

“Maybe not at the time, but you can imagine – a tall, charismatic, charming man who is imbued with a sense of destiny. He genuinely believes that his father is going to be king and then he is ultimately the next king.

“He grew up with this sense of self-worth. Of course, that all came crashing down and he really struggled to deal with that in the aftermath of Culloden.

“But I think a lot of the fascination has to do with this glorious failure. I think his character flaws would have become more known had he succeeded.

“But we only tell his story for a very short period of time.

“We basically tell the story of a 23, 24, 25 year old and that’s it. We never tell the story of a 60-year-old. We never tell the story of the five-year-old.”

Outlander: fact or fiction?

Katey appreciates some people criticise the accuracy of Outlander, which is based on historical fact.

But it has to be remembered as a piece of fiction.

She adds, however, that Outlander is a great way into the story of Culloden and for people to find out more for themselves.

“One of the things we noticed here when we had lots of visitors was that people were coming with the story of Outlander and what they wanted was to find out the real history,” she says.

“I think that fiction is an incredible way into complex and divisive history.

“But it also reminds us that this was a time of brutal civil war which ripped apart lives and families.

“It’s difficult for us to imagine just how terrible a time it was.”