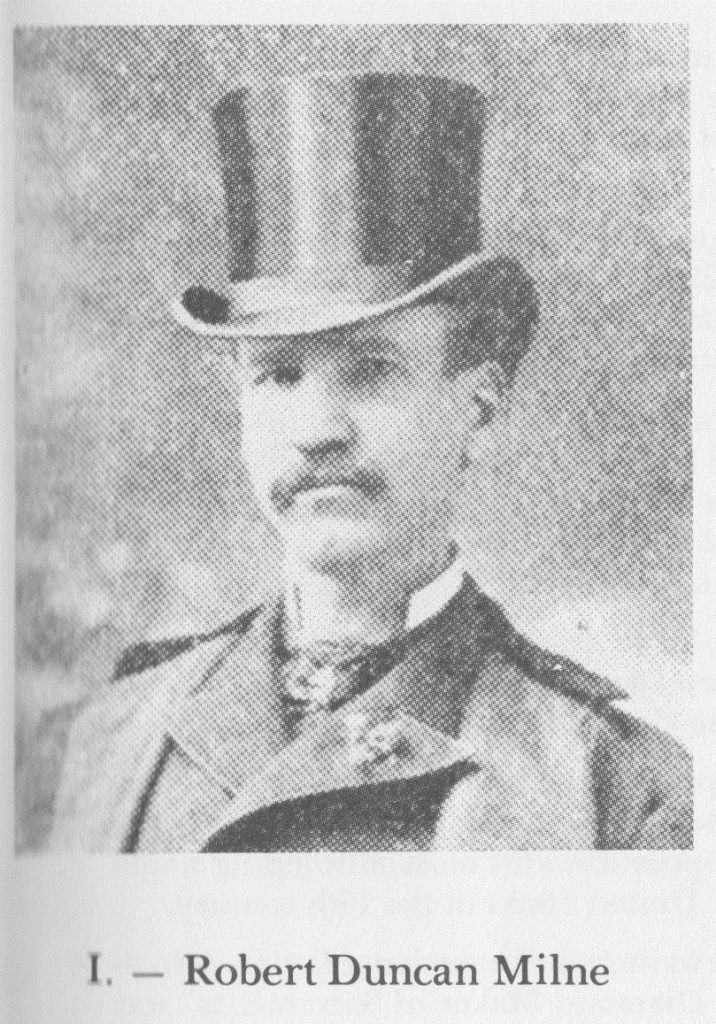

He is thought to have been the world’s first full-time science fiction writer. He was friends with Robert Louis Stevenson. His stories contained inventions and ideas that would become reality but not for another 100 years or more.

Yet the name, life and work of Robert Duncan Milne were almost completely forgotten until Courier archivist Barry Sullivan stumbled across him.

The 45-year-old went to Dundee University as a mature student, studying English literature and film. One day he picked up a book by American sci-fi historian Sam Moskowitz.

It contained a short section about Robert Duncan Milne, a 19th Century science-fiction author who became a major figure in the Californian literary scene.

“Milne was born in Cupar, which is my home town, so immediately my ears pricked up,” Barry explains.

“I checked with the local historical society and with the library but no one had a clue who he was.”

Barry set about unearthing the mysterious writer’s past, discovering details of his life and reading his stories. “The more I read the more I realised he deserves recognition.”

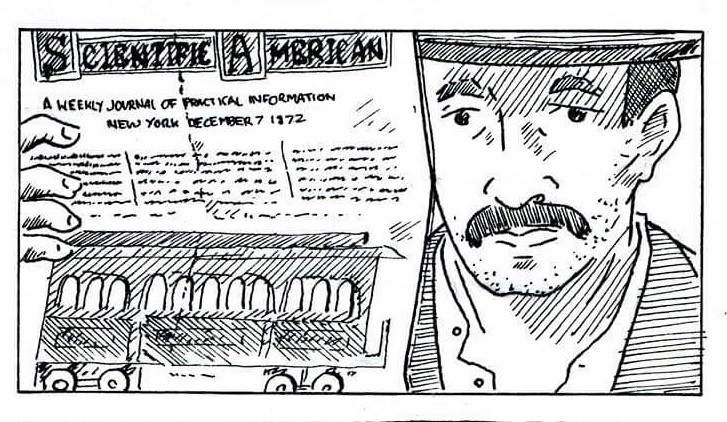

Barry brought his findings to his tutor, Dr Keith Williams, who has now commissioned a PhD on Milne’s life and work. Another student will be carrying out the PhD – Barry doesn’t have time, although he is working on a graphic novel based on Milne’s life and works.

The son of Reverend George Gordon Milne, the town’s Episcopalian minister, Robert Duncan Milne was born in 1844 at Carslogie House in Cupar. He went to Glenalmond College and then Oxford, where he studied classics.

After university he emigrated to California where he dropped off the radar for the best part of a decade, working as a shepherd and then, somehow, becoming an engineer. When he resurfaced it was at the 1874 San Francisco Mechanics’ Fair where he was demonstrating a new type of rotary engine.

It failed to generate financial success, however, and Milne turned his hand to writing, publishing a series of apparently biographical short stories in the city’s Argonaut newspaper. These detailed his time working as a shepherd, cook and labourer in California and northern Mexico during 1872-73.

It’s unclear why he had to turn his hand to manual labour: in addition to being Oxford educated he regularly received money from his wealthy uncle, Duncan James Kay – a founder of Barings Bank.

What’s also unknown is why he switched from folksy autobiographical tales of itinerant labouring to imaginative and inventive works of science fiction.

Whatever the reason, his stories were popular and around 60 of them were published in The Argonaut before his death.

They were filled with densely packed detail about fantastical inventions. “The clever thing he did was mixing real science and engineering in with the speculative stuff,” Barry explains. “The reader has to work hard to unpick what’s real and what’s made up.”

Among the inventions Milne presaged was the mobile phone, which featured in a story called The Great Electrical Diaphragm.

“He also envisaged a film around the earth which signals could bounce off and be transmitted all around the world,” Barry says.

Other stories predicted the rise of cinema as an entertainment form, the ravaging of the earth by a comet strike, drone bombers, self-guiding missiles and suspended animation.

Although all but forgotten today, Milne was a major figure of his time. His stories were hugely popular. He was friends with Robert Louis Stevenson and, indeed, helped the Treasure Island author sell his stories when he washed up penniless in San Francisco.

Milne was a high-functioning alcoholic and it appears his uncle eventually stopped wiring him money after he blew a large transfer of cash on a bender.

His end came on December 15, 1899 when he stumbled drunkenly in front of one of the first cars in San Francisco. It was a sad end for the 54-year old sci-fi pioneer. “In the end it was modernity that knocked him dead,” Barry explains with a wry smile.