“Ne’er ye mind fit fouk say, bit dee ye weel an lat them say” was inscribed in granite on his grandfather’s tenement at Jackson Terrace, Aberdeen.

Samuel Irvine Rae had the same doric motto cast in concrete by the door of his own home, the Garpit Farm, Tayport, which he restored in the 1970s. The right medium and mantra for the man who built the country’s largest independent building materials supplier from the ground up.

Brand and Rae began in 1948 with an unlikely dual purpose: Colin Brand wanted to build boats, while his brother-in-law Irvine Rae saw a less romantic opportunity in precast concrete blocks. With post-war construction booming, the firm acquired headquarters at Russell Mill near Cupar and a fleet of garish orange lorries. At the helm, Irvine was the ultimate salesman, offering clients cigars to detain them long enough to flog his wares and even crashcoursing Gaelic to charm his West Highland customers.

While blocks and tiles were Brand and Rae’s bottom line, the firm also cast civic art for the new town of Glenrothes including its iconic bloat of concrete hippos. He insisted that employees never worked ‘for’ him, always ‘with’ him and pioneered placements for disabled workers.

While Fife was home for 70 years, Irvine was an Aberdeen loon. He was born within spitting distance of the Kittybrewster Mart, where childhood games involved running the gauntlet among livestock.

Aged 11, Irvine received a hard lesson in dealing with wily characters when he was enlisted to help herd a flock of sheep to the Brig o’ Dee in his wellies. The farmer left him there with blistered feet and a penny for his troubles, not even enough for the tram home. The exploitation was reported to the Mart’s directors by a sympathetic ticket inspector. The farmer was banned for two months and forced to stump up £2 to young Irvine — the equivalent to a week’s wages for a drover.

A lithographer’s son, Irvine attended Sunnybank School before becoming the first dux of the new Powis Secondary. In the 1980s he discovered that he had been omitted from the school’s honours board. This was swiftly redressed and he donated the annual prize to the school’s top pupil ever since.

Irvine was an auspicious junior golfer at Murcar, besides a prizewinning young athlete. Formative years in the 3rd Aberdeen Boys Brigade anchored a lifelong sense of discipline, and he learnt to play the baritone in the BB band.

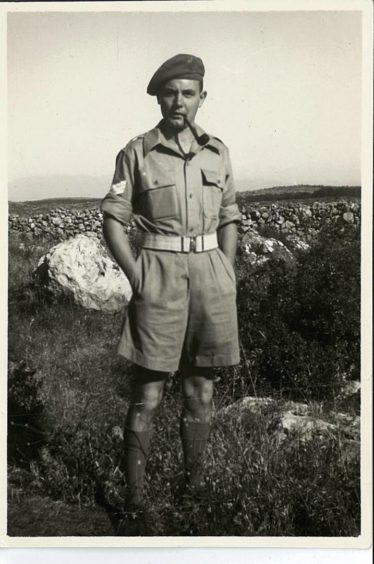

Following his father into the printing trade, Irvine served his apprenticeship with John Avery and Co. and in 1942 was called up to 514 Field Survey: Map Reproduction Section of the Royal Engineers.

Sergeant Rae produced the maps for the D-Day landings, landed on Sword beach and set up a makeshift frontline printworks. From there he gathered intelligence on enemy positions and produced the maps required by Allied commanders. Irvine would personally relay the latest editions by motorbike, dodging booby traps and pop-shots from Luftwaffe gunners.

Samuel Irvine Rae’s initials ‘SIR’ proved a self-fulfilling acronym as a chevalier of the Légion d’honneur in 2017, France’s highest order of merit, for his part in helping to liberate Europe.

Though war ended in 1945, Irvine continued with national service in Palestine, where an encounter with a roadside bomb saw him jettisoned through the roof of his vehicle into a nearby thorn bush. Posted to Greece to help with postwar rebuilding, he printed the first drachmas after the hyperinflation of Nazi occupation.

Irvine always had a wise word for his nine grandchildren: “ye hae twa lugs and ee’ moo – use them in that proportion”. He seldom did, blethering to everyone, taking interest in everything and knowing that every acquaintance made might prove invaluable.

Some years later, Irvine’s daughter, Ishbel, went missing in Greece. He phoned the Hellenic Police switchboard, asking in pidgin Greek after an officer he had known in the forties. The young man had since become Athens’ police chief and within the hour authorities were on high alert, and confirmation received that Ishbel was not in a police cell, hospital or morgue.

Demobbed, Irvine returned to Aberdeen. John Mearns, the well kent folksinger, was a neighbour of the Raes and a young champion highland dancer Louise MacRae performed in his concert party.

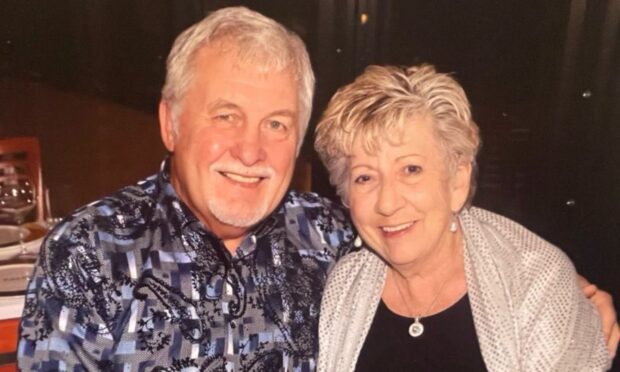

Louise was a striking beauty, a covergirl on shortbread tins exported across the world. When Irvine and Louise married in 1952, Aberdeen’s Evening Express gave the headline to the star of show: ‘HIGHLAND DANCER WED’.

Irvine and Louise made Tayport their home, raising three children and immersing their lives in the community.

Tayport Instrumental Band formed in the 1860s, but folded in the interwar years. In 1968, Irvine dusted off his baritone, reconstituted the group and by 1971 they were on stage at the Albert Hall competing in the top tier of the Brass Band Championships.

Irvine bought Tayport Printers, ran a market garden, chaired the North East Fife Conservatives, taught Scottish country dancing, was an active mason and kirk elder and captained Scotscraig Golf Club.

A great passion was fishing and Irvine was most at home in the Angus glens or Cairngorms. Redhall Cottage on the Cortachy estate became basecamp for many family holidays.

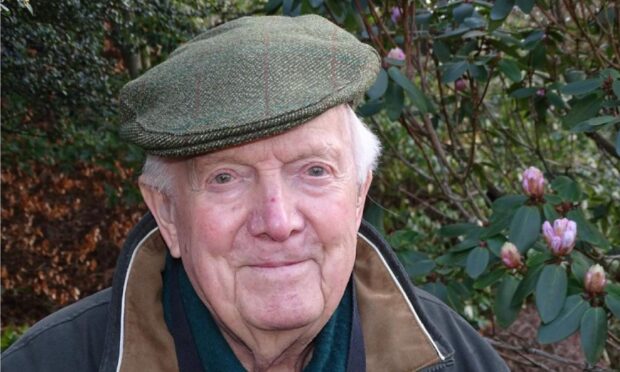

Irvine was a serial entrepreneur and a man o’ pairts in the best tradition of honest, industrious, community-minded Scots. Above all, he was a devoted husband to Louise, father, grandfather and friend to many. He may “ne’er hae minded fit fouk said”, but it was seldom anything but admiration.

Samuel Irvine Rae was born on May 30, 1924. He died peacefully on January 7, 2021, listening to the Black Dyke Brass Band and his favourite bagpipe tune, ‘Lochanside’.

His ashes are to be scattered from the summit of Lochnagar.