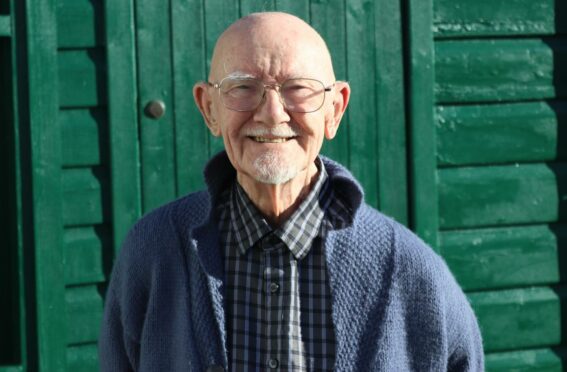

Harry Gillan, who helped to save an estimated two thousand children from starvation during the Biafra war, before serving as depute rector of St John’s High School, Dundee, has died aged 93.

In the 1960s, as a Marist Brother committed to educating needy children, Harry, known then as Brother Raphael, was headteacher of a boys’ secondary school in south-east Nigeria.

He, his fellow brothers, pupils and local residents were trapped in their region when it declared itself independent Biafra.

The Nigerian national army admitted using starvation as a weapon of war. By the end of the war an estimated 3.5 million people, most of them children, had died of hunger.

Brother Raphael showed exceptional bravery, facing down gunmen and driving vehicles into conflict zones to try to find food and medicine for children.

Starvation was eventually eased when Joint Church Aid, nicknamed Jesus Christ Airlines, launched an airbridge from a Portuguese controlled island into Biafra.

It lasted one-and-a-half times longer than the Berlin Airlift, saved an estimated one million lives, but claimed the lives of 25 civilian pilots.

Flight to freedom

Brother Raphael was imprisoned towards the end of the war but escaped to safety by fleeing through the jungle.

Harry related much of the story of his remarkable life to neighbour and fellow former teacher Piers Bowser during lockdown last year.

He was born into humble circumstances in Hilltown, Dundee, in 1928, one of two sons of Alexander and Bridget Gillan.

He was educated at St Mary’s Forebank Primary School, run by Marist Brothers.

When war broke out, he spent a short period as an evacuee in Montrose before returning to Dundee and continuing his education at Lawside Academy.

He then moved on to St Joseph’s College, Dumfries, and at the age of 17 received his religious name, Brother Raphael, and embarked on his Marist life.

Harry had wanted to become a modern languages teacher but had such a talent for maths that he was persuaded to study science and maths at university.

Career path

After graduating BSc in maths and astronomy from Glasgow University, Brother Raphael spent a year in teacher training at Jordanhill College before taking up a post at his old school in Dumfries.

Just three months later, Brother Raphael was offered a post at a newly opened Marist-run school in Nigeria.

It took three weeks by boat to reach the 350-pupil school where he lived in similar conditions and received the same salary as local teachers.

He installed a generator providing electric power to the school where four local languages were spoken.

Unrest

In October 1960, Nigeria gained independence from Britain but in a country of 55 million people and 200 racial groups, tensions soon surfaced.

A massacre of 30,000 people in the north of the country was the catalyst for the south-east to declare an independent Biafra.

Heartbreaking horrors followed but the Marist Brothers were determined to show their neighbours they were not just there in the good times.

The brothers opened a small clinic and Brother Raphael would travel by lorry to loot abandoned shops to keep starving children alive.

On one mercy mission, gunmen ordered him to hand over his lorry load of food.

Brother Raphael, sensing hesitation, grabbed the weapon and threw it into the undergrowth.

Suddenly, he found himself on the ground, shielded by friendly militiamen who feared he would be shot.

In another incident after Brother Raphael and his fellow brothers had rescued equipment from an abandoned hospital, he settled down at night to listen to the BBC World Service.

Conflicting reports

He told Piers that he heard BBC war correspondent Frederick Forsyth, who was only 20 miles away, saying could hear the fighting and bombs going off, yet Brother Raphael could hear not a sound.

In 1969, he was captured by the Nigerian army and although he was treated well he made his escape and moved from village to village, picking up abandoned cars.

When the war ended Brother Raphael was six-and-a half stones, having lost three-and-a-half stones during the blockade.

The war had taken a psychological toll on Brother Raphael. He spent several months recuperating in Rome and various other Marist houses before taking on temporary teaching posts in Wolverhampton and Newcastle.

Questions of faith

It was a period when he asked: “Where is God in all this?” His faith was under strain, he stopped reading the Bible, took the decision to leave the Marist order and returned to using the name Harry.

Eventually he applied for, and was appointed, principal teacher of maths at Perth High School. He joined a hillwalking group and enjoyed many weekends finding solace in the hills of Scotland.

In 1975, Harry was appointed depute rector at St John’s High School, Dundee, where he remained until his retiral in 1992.

His former colleague, Tony Cousins, a former depute rector at St John’s, said Harry regained his faith.

Tribute

“He was a believing Christian and I think he had become reconciled to some of the decisions he had to take during the famine in Biafra and the things he had seen.

“When he returned from Africa I believe he had been suffering from PTSD. The condition was not recognised back then and Harry had to struggle on alone.

“But he became an inspiring teacher. He was good at his job, a respected teacher who gave his life to the school. Harry was well loved by his colleagues and his pupils.”

During his time at the school Harry met the school auxiliary, Betty McDonald, a widow who had been working at St John’s for a few years.

They discovered that they enjoyed each other’s company and soon became inseparable, marrying on July 3, 1982. Both considered themselves very lucky to have found each other in later life.

Marrying Betty, Harry gained four stepchildren and, eventually, became a proud and loving papa to nine grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren.

Harry was very much a family man who loved spending time with the family, playing board games, cards, petanque, garden badminton, reading stories, showing the children magic tricks and playing music and he was always available to offer guidance to the younger generations.

Retirement opened up opportunities to travel and visit family and friends in various places including America, France as well as the UK.

They were a very sociable couple having many friends, good neighbours and an open door to all. They were also able to spend time developing their many talents and hobbies and enjoyed a very long and happy life together.

Betty was diagnosed with Alzheimers in 2013 and Harry cared for her until her death in 2018. He missed her daily and spoke of her as his soulmate.

Harry’s neighbour Piers included parts of his interviews with Harry in a video.

It also shows Harry being greeted by his neighbours on his 92nd birthday.