In 1946, John Purvis from St Andrews played among the ruins of Hamburg with a German boy of the same age.

His father, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Purvis, was responsible for securing food for starving Germans.

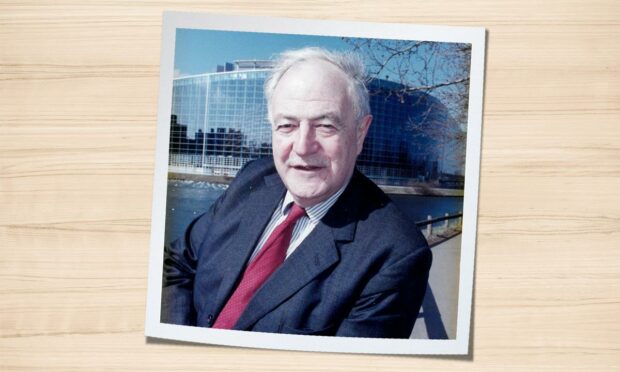

That exposure to the devastation caused by war in Europe was to shape young John Purvis who went on to have a career in banking before representing Mid Scotland and Fife in the European Parliament.

John, who had an unstinting belief in Europe and of the power of friendship to bridge cultural divides, has died aged 83.

Innovator

He will also be remembered as one of the developers behind the creation of ATM cash dispensers.

In 2001, John’s belief in the need for a united Europe was summed up up in a speech he gave to the European Parliament as his father lay gravely ill in Scotland.

He said: “The European Union and this parliament are our family’s guarantee that the peace and security for which my father has fought and worked in his lifetime will indeed continue for future generations.”

Beginnings

John Robert Purvis was born in St Andrews to Robert and his mother Vivienne, who grew up in Calcutta.

During his early years, his father was often overseas, deployed with army’s Special Operations Executive on top-secret war missions in Yugoslavia and France.

His mother kept the farm going with a team of Land Girls and Italian prisoners of war.

After school at Cargilfield in Edinburgh and Glenalmond College in Perthshire, John was called up for National Service and served as a lieutenant in the Scots Guards from 1956 to 1958.

He attended St Andrews University, studying political economy and moral philosophy from 1958-1962.

There he met an American exchange student from Virginia’s Sweet Briar College, Louise Durham. Louise would become his wife for almost 60 years.

From student days he travelled intrepidly, notably on a daring 1961 overland voyage from Leuchars Station to Tanga, Tanganyika, via steam train, river steamer and car.

Banking

It was John’s 1960s career as an international banker for First National City Bank – now Citibank – in London, New York and Milan, that first convinced him of the ability of shared economic interests to unify people and countries

It also exposed him to business leaders like Walter Wriston.

The bank’s culture of innovation encouraged him to experiment with ideas, like the new formulae for credit analysis he developed using the enormous punch card computers in the New York office.

Cash machines

A few years later, he and colleague Jerry Mitchell submitted a proposal to Wriston for “a machine which could recognize signatures or thumbprints and would be able to dispense cash” – effectively the first ATM.

Several years later Citibank opened its first ATMs with some fanfare.

John’s interests at the bank were not confined to the economic. He felt comfort and style was essential to a good customer experience, so he committed to transforming the Milan branch.

Stylish

Lower teller counters, a Venini glass map of the world, comfortable seats and foyer coffee, made it warm and inviting.

Colourful cheque book covers he commissioned from Florentine designer Emilio Pucci, became coveted collectables, snapped up by the New York headquarters for its wealthiest clients.

In 1969 John returned from Milan with his wife and three children to live on his father’s farm near St Andrews.

Enterprise

He worked in merchant banking for Noble Grossart in Edinburgh and then set up his own international consultancy.

Politics had never been in the picture, until Sir John Gilmour – then Conservative MP for North East Fife – pointed out that his finance background, international outlook and sociable personality would be a great fit for the first European Parliament.

Politics

Elections were due to take place in June 1979. In the heavily Labour constituency of Mid Scotland and Fife, winning would be a long shot. John decided to take the risk and won to his great surprise.

The members of the first directly elected European Parliament were a diverse group, including names like Simone Veil, Barbara Castle, Sheila de Valera, the Rev Ian Paisley and Willy Brandt.

Simultaneous translation ensured MEPs could communicate easily in their mother tongues.

It was an ambitious exercise in international democracy which John found invigorating.

His sense of humour and genuine interest in people of all cultures and backgrounds, allowed him to develop effective working relationships and lasting friendships across ideological and national boundaries.

Through his work on the economic and monetary affairs and energy and research committees, he felt he was making a difference in reducing red tape and improving standards for millions.

John also welcomed proposals for new freedoms to study and work across the continent and believed the European Community provided a vital “third bloc” to counter-balance the economic and political muscle of the US and China.

Frustration

It was definitely a frustration when the British Press and some UK politicians used Europe as a scapegoat.

Nations were lining up to join the EEC but John felt blue passports and bendy bananas often garnered more attention in the UK.

Faith

John’s collaborative instincts and deep Christian faith led him to set up the first cross-party group in the European Parliament, the European Parliament Prayer Breakfast, which is still active today.

Another lasting legacy was his contribution to the Delors Commission. This policy group put forward plans for the first European currency. This was provisionally named the Ecu but eventually became the Euro.

As expected, John lost his seat to Labour in 1984, resiliently resuming his consulting practice.

During this period he was appointed Member for Scotland on the Independent Broadcasting Authority and awarded the CBE in 1990.

However, he missed the fascinating policy work and melting pot of cultures in the European Parliament.

In 1999, 20 years after his first term, he stood again as an MEP for Scotland and won again.

He remained a highly committed MEP and vice-chairman of the economic and monetary committee until he retired from the European Parliament in 2009.

Towards the end of his term, it became challenging to reconcile his unstinting belief in Europe with the Conservative party’s increasingly eurosceptic outlook.

When the Brexit referendum reared its head, John criss-crossed Scotland speaking over 100 times to business, student and community groups in support of a Remain vote.

Brexit

His efforts paid off in Scotland, but not in the wider UK. After Brexit, John continued to advocate for Scotland and the UK’s place at the heart of Europe, setting up the campaigning group Fife for Europe in 2017 and being appointed co-president of European Movement in Scotland in 2021.

John ran the family farm and loved his garden, planting and nurturing a collection of more than 100 species and hybrid rhododendrons.

He was diagnosed with a brain tumour in early September 2021. Despite this, he was still participating in discussions about security and prosperity in Europe into his final days and was particularly concerned about the situation in Ukraine.

He is survived by his wife Louise, children Elizabeth, Emily and Robert, 10 grandchildren and one great grandson.