The family of Enid Gauldie have paid tribute to the Invergowrie writer, book-seller and historian who has died at the age of 96.

Enid was a free thinker and fast learner and her observations led to the proper documentation of the declining Scottish textile industry and inner-city slum dwellings prior to their demolition.

She was born in Liverpool in 1928.

Enid was the oldest of two daughters to William Macneilage and his wife Annie Green.

Her parents moved to Broughty Ferry in 1934, when her father became manager of the West End Garage in the Dundee Road.

The family lived first in James Place and then Strathearn Road.

Having started school in Liverpool, Enid could already read and write, so she was placed in a class of older children.

She attended Grove Academy and went on to become a student at Queen’s College.

It was a college affiliated with the University of St Andrews that eventually became the University of Dundee in 1967.

Enid edited the student mag The Glad Mag while at university.

Friends made during her time at the Grove Academy and at university remained with her throughout her life.

After graduation, Enid became a librarian, first with Dundee Public Libraries and then the University of St Andrews.

Lifelong interest in antiquarian books

Many of the books she was overseeing there were ancient, often Medieval times and this sparked a lifelong interest in printing, publishing and antiquarian books.

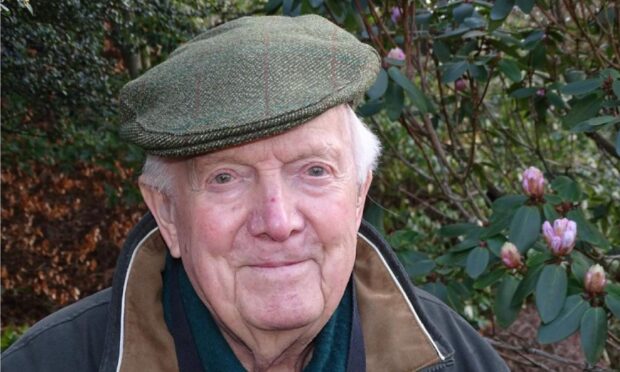

In 1949 she married architect Sinclair Gauldie and moved to Invergowrie.

He designed and built their house, which appeared in many design publications of the period.

Her personal taste was for Georgian properties, which her husband thought to be cold and outdated.

As it turned out, it was to be Enid’s home for 75 years.

As she grew older she learned to appreciate the beauty of the garden she herself built and the surroundings she lived in.

It was her constant wish not to have to leave and her family find comfort in the fact they could make that possible.

Convention dictated that she give up her job when she married.

But she started to write and soon won a competition for a Vogue magazine job.

However, Enid was unable to accept the position due to the restrictions of married life and travel.

She continued to contribute to various publications, writing on a wide variety of topics, including a regular interior design column for D.C. Thomson, but received no bylines.

Enid and Sinclair enjoyed a very varied social life.

This revolved around the arts and history in Dundee, including the Rep theatre and the couple had many friends in Dundee’s extensive artistic community.

Early member of Abertay Historical Society

An early member of the Abertay Historical Society and a fierce fighter for the preservation of industrial heritage, Enid had many battles with councils and private individuals about the need to preserve objects and buildings which would otherwise have been lost.

She was extremely proud that the Telford Beacon, due to be demolished to make way for the Tay Road Bridge, was one of her successes.

After it was moved again, to make way for the rejuvenation of the esplanade area, she was keen to check it had indeed been rebuilt.

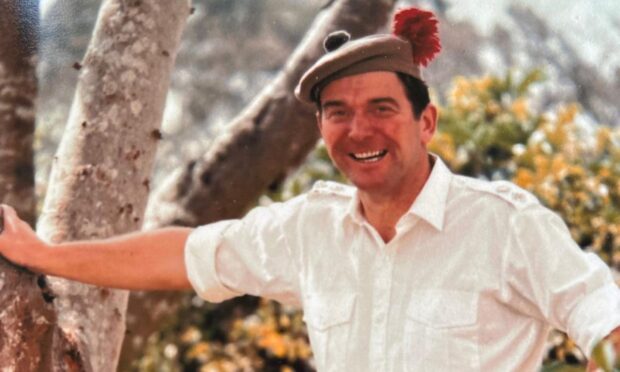

In 1954 Enid gave birth to her son Robin, followed by Alison in 1957.

During the 1960s an opportunity to complete an MA in History came her way and she returned to university to do so.

By 1967 she had graduated and became a staff member in the Modern History department of the new University of Dundee.

Her interests included the textile industry and Scottish social and economic history, much of her research revolving around the textile mills and tenements of Dundee, which had fallen into serious decline.

Her research saved objects and images for future study and of this, she was immensely proud.

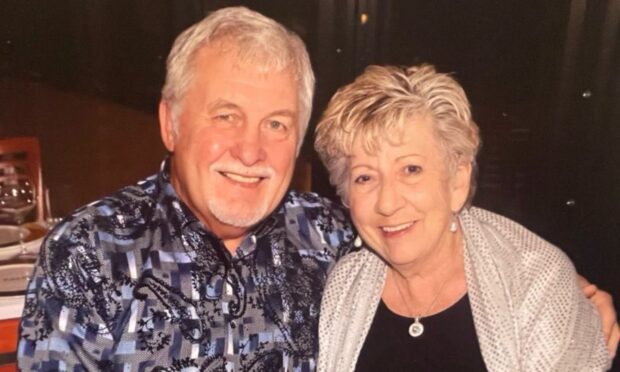

Despite a third pregnancy, Enid managed to publish two books in 1969, both on the Scottish textile industry.

The birth, of her daughter Becca, brought a halt to her university career.

But she continued to be published, producing Cruel Habitations, published by George Allen and Unwin, in 1974.

And then The Scottish Country Miller, published by John Donald, in 1980.

What subjects did Enid’s books cover?

Her publications covered a wide range of subjects including local history, Dundee blue bonnets, spinning and weaving in Scotland.

She also published several works of fiction.

Enid also found time to be a long-term member of the board of Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and volunteered for the Oxfam shop which was situated on Dundee’s Perth Road.

There she invented biannual antiques sales, of donated clothes and objects, which were particularly well received by the nearby students.

After her husband died Enid embarked on a completely new career path.

Launching a book business

Encouraged by her antique dealing daughter Becca, she launched an antiquarian book business, Scribe Books.

She accompanied her daughter far and wide across the UK and became well-known throughout the trade, from London to the North of Scotland.

Their shop, in Glendoick’s old school, was an easy stopping off point for many and they both thoroughly enjoyed the social side of meeting collectors and connoisseurs of both books and antiques.

A second hip operation put an end to her book business.

But she remained an avid reader until her final days.

One of her last outings, only two weeks before her death, was to Dundee’s Oxfam book shop and she acquired three novels and two volumes of poetry.

Even as her daughter took on a caring role, they were never short of things to say to each other, despite being together almost 24 hours a day.

In addition to her caring duties, Becca continued to maintain and expand the garden started by her mother and this gave Enid immense pleasure and comfort.

Small in stature but huge in presence, she leaves a huge chasm in the lives of her family and remaining friends.

A staunch atheist who believed in no afterlife, she did not want a funeral.

Enid, who passed away on December 14, is survived by son Robin and daughter Becca. Her eldest daughter Alison passed away in 2021.

Conversation