For most, if not nearly all of us, a first flight is a comfortable seat in a modern air-conditioned airliner.

Days after VE-Day in 1945 with World War Two still raging on in the Far East it was a very different experience for a young woman from Yorkshire.

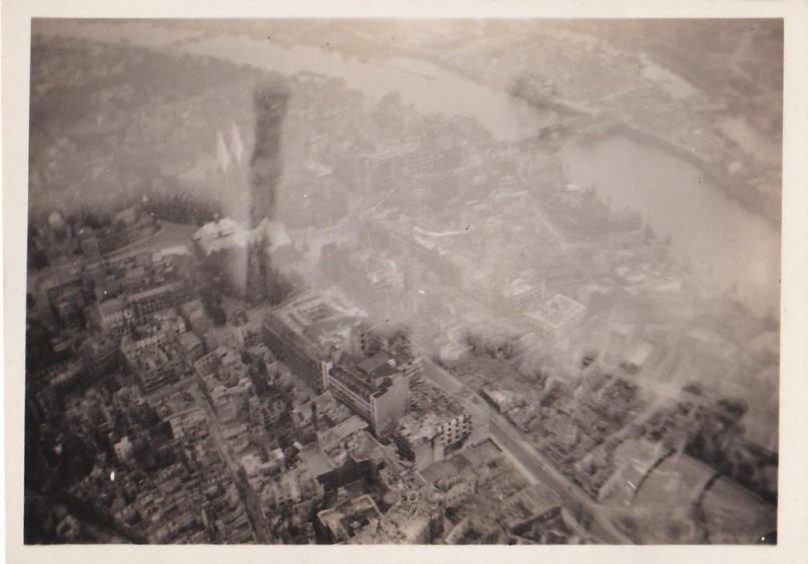

As the four powerful Merlin engines of the Lancaster bomber held their steady note over the skies of Germany, Corporal Fourness, M, Service Number 474762, lay flat on the floor in the bomb aimers cramped area at the front.

As the target loomed in sight 23-year-old Fourness kept as steady as possible.

Then, at the critical moment, the young corporal on a unique first flight pressed the operating mechanism to achieve the mission.

The equipment Cpl Fourness was using was not some ingenious WW2 invention.

It was a Box Brownie camera first produced by Eastman Kodak in 1900 and retailed at one dollar.

What was so different about this flight over war-torn Germany was not just that someone below the rank of sergeant was travelling in a Lancaster bomber but the fact she was one of two women on board.

Margaret Overend settled in Strathkinness

Mrs Margaret Overend as she became eventually set up home in Strathkinness by St Andrews.

She passed away on February 17 a month before what would have been her 103rd birthday.

In 1945 Margaret and her best friend LACW Kathleen Turner were based at RAF Topcliffe in Yorkshire.

They accepted an invitation from a Canadian aircrew to go on the flight in a beaten-up Lancaster.

The aim was to get, for intelligence purposes, official photographs of bomb damage, and to drop leaflets for humanitarian reasons.

Earlier in the war, leaflets were used for propaganda purposes, urging Germans to abandon their homes – and their leaders.

In Margaret’s flight, the leaflets gave details of German POWs.

What did Margaret Overend think when she saw bomb damage?

Margaret had a stellar career with the Midland bank but when she joined the WAAF (Womens Auxiliary Air Force) they had her doing vital war work – washing dishes.

“Then, one day, a senior officer asked me what I did in civilian life. When I told him I worked in banking I was suddenly lifted out of the kitchen and into the pay section!” she recalled with a smile in a recent interview.

For the entire six-hour flight which stretched over one thousand miles the two women had to lie on their stomachs in the small area usually only occupied by the bomb aimer at the front.

That day there were three crammed in the space.

As the aircraft flew over wrecked city after wrecked city, the official Intelligence photographers did their work.

Margaret’s Box Brownie captured a few images, limited though they were by the rudimentary nature of the camera, and the cloudy conditions.

She kept them as a memory of the trip.

“As we looked down at the damage done by constant bombing I thought what I was seeing was simply appalling,” she recently recalled.

“On the other hand you have to remember what the Luftwaffe did to our cities like London, Coventry, Liverpool and many others.”

Devastation of cities was caused by German and RAF bombers

What happened in the Clydebank blitz of March 1941 is a grim example of that.

The official death toll was 528 dead in the town.

That included 14 members of the extended Rocks family at 78 Jellicoe Street.

Patrick Rocks Snr came home from work to find utter devastation and his entire family gone, including his own wife and children, and his son, daughter-in-law and their family. The victims included five children aged six and under.

The same hideous nightmare was undoubtedly played out in German cities like Hamburg, Cologne and Dresden, as Sir Arthur “Bomber” Harris, head of RAF Bomber Command deployed his aircraft, often a thousand at a time, to pulverise areas of cities rather than specific targets.

That is what Margaret gazed down on in the historic, unique opportunity afforded by the flight, as the photo evidence shows so graphically.

For the Canadian aircrew on Margaret’s flight it was almost a perverse opportunity to see in daylight for the first time targets they had bombed many times at night.

The navigator remarked they had been to the Ruhr so often the Lancaster knew its own way!

Margaret Overend was a committed member of Fife community

For Margaret, the trip was anything but business class travel.

They were not in danger of being shot down but the Lancaster had had lots of war wounds and repairs done to keep it flying – just.

Leeds-born Margaret married bank manager Ken in later life and their travels took them far and wide.

They settled in Fife and had many happy years before Ken passed away.

Margaret was very active in the area being treasurer at a voluntary group and helping bereaved people.

Both Margaret and Ken were only children and had none of their own.

She used to refer to a significant number of younger colleagues at work as “my children.”

She kept in touch with huge numbers of them.

Christmas Day was spent chatting to a seemingly endless number of them worldwide on the telephone.

How Margaret inspired Strathkinness Primary School children

Margaret lived a couple of doors down from Strathkinness Primary School.

Over several years a ritual evolved where pupils passing her window, whether on the way to the local park for gym classes or just coming and going to and from school would stop and wave.

Margaret loved sitting by the window and happily returned the compliment.

She also sponsored bus trips for the pupils to places like Blair Drummond safari park.

On her 100th birthday everyone one of the 62 pupils sent her cards.

Mrs Kate Balsillie, the head teacher, said the pupils got so much from the relationship.

“For the pupils it gives a sense of community involvement and acknowledgement that there are people in the community we can value and make a difference for.”

Margaret told me of two final wishes. Most important, she was to be reunited with her beloved Ken.

“And if I don’t make it to my (103rd) birthday party just have the party without me,” she said.

Truly a wonderful lady making memories to the end.

Conversation