“On Monday August 13 1894, residents in Muskegon, Michigan opened their local newspaper, the Muskegon Chronicle, to discover that two of the most popular and critically acclaimed writers of the day – Robert Louis Stevenson and JM Barrie – were engaged in correspondence.

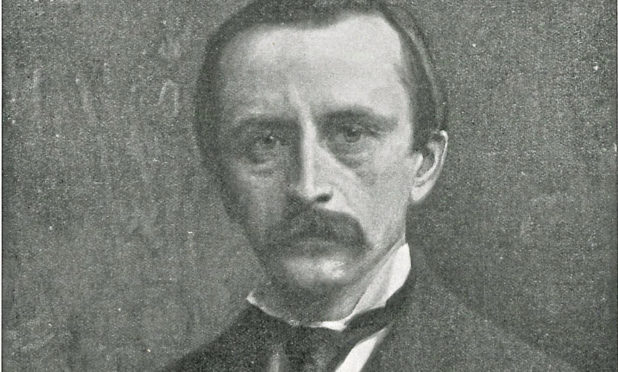

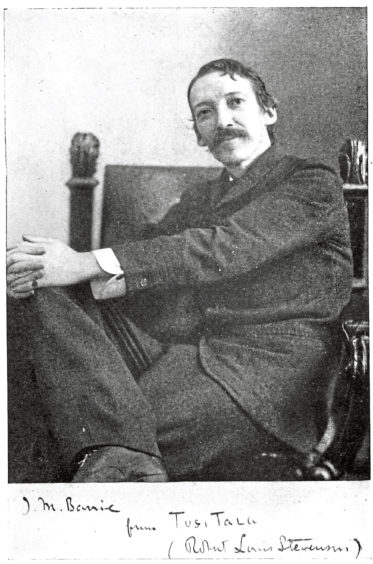

“Adorned with illustrations of both writers, the paper’s gossip column ran an article on their rumoured friendship which noted that they had become the “warmest friends”, with Barrie known to write “reams of letters to Stevenson”.

“The Muskegon Chronicle wasn’t alone. From Dundee to Massachusetts, from Illinois to Alabama, newspapers were carrying the story that a friendship between Stevenson and Barrie had blossomed through correspondence.”

So begins A Friendship in Letters – Robert Louis Stevenson and JM Barrie’, a new book edited by Stirling University lecturer in Scottish literature, Michael Shaw, and which I have just read for the second time since it was published shortly before Christmas (I self-gifted while I was doing my Christmas shopping). The Dundee newspaper rubbing its hands at the revelation in 1894 was, of course, this one.

Fast forward to October 1997, which is when this column drew its first breath, and with the world for my oyster, I chose to write about JM Barrie. There were two reasons. One was a news story about plans to build a kind of Barrie theme park in Kirriemuir. It didn’t happen. I like to think I helped to make it not happen.

The other reason was that not long before my mother died in 1993, she revealed her theory about where my writing genes came from. Her mother was a Barrie whose family came from Milton of Campsie although she lived much of her young life in the north of England. She told me that according to someone she called her “Uncle Stanley”, both he and her mother were cousins of JM Barrie.

When I was christened, I got the James from my father, but my middle name is Barrie, at my mother’s insistence. Maybe she knew what she was doing all along.

Rather than risk disappointment…

I was already an unsuspecting admirer of JM Barrie’s novels before my mother proclaimed our shared lineage (not so much a revelation as an insinuation) and fired my imagination. So is it true? I don’t know. Is it better to dine out on the possibility or discover the truth and risk crushing disappointment? Okay, mild disappointment. I could probably find out with a couple of hours on my laptop, but I never have, which rather seems to answer my own question.

A handful of years ago, I added to my small collection of Barrie books a printed copy of Courage, his rectorial address to the students of St Andrews University in May 1922. The original owner had written inside: “Neil Smith, Christmas 1922”. Underneath I have written my own name and “Christmas 2014”. I was obviously self-gifting again.

I didn’t go to university. I joined this newspaper at 16 instead. The university world is a mysterious and unexplored one to me, but I bought the little book because after reading the first couple of pages in the shop, it was like hearing his voice for the first time. The beauty of A Friendship in Letters is that it does that in spades. And of course the same is true of Stevenson’s voice.

A wonder of jokes, compliments, criticism and ideas

The conversation – for that is how it comes across – is a wonder of jokes, mutual compliments, mutual occasional but surprisingly blunt criticism, ideas, philosophies, and an intimate, even tender, exploration of a down-to-earth friendship that belies the fact that they were both superstars.

Thomas Hardy was a friend to both men, which doesn’t stop them having a go at some Hardy characters. I have just re-read Hardy’s The Return of the Native, probably my favourite Hardy story. (I used to think it was Far From the Madding Crowd but probably that was more of a Julie Christie thing.) But shortly before that I had re-read Barrie’s The Little Minister. I don’t mind admitting that Barrie’s admiration of Hardy is evident there, but nor do I mind admitting that I think Barrie’s is the better novel. And he has better jokes than Hardy, and there are more of them.

Why so few Barrie books today?

And here’s the thing: half a dozen of Hardy’s novels are still in print in handsome hardbacks as well as paperbacks, Stevenson likewise. With the obvious exception of Peter Pan, Barrie’s books are unforgivably absent from the classics lists of 21st Century publishing. It astounds me.

Even if you were to narrow the field to contemporary Scottish publishing, there are modern editions of John Buchan, Neil Gunn, Walter Scott, Lewis Grassic Gibbon. But Barrie’s appeal was far wider than Scotland, and like Stevenson, he was a huge success in America.

The Barrie that emerges from the pages of A Friendship in Letters is the Barrie I glimpsed in the rectorial address but always hoped to know better. Now I do and I’m grateful. He told those St Andrews students all but a hundred years ago that “you remember someone said that God gave us memory so that we might have roses in December”.

January too.