We don’t need a degree in psychology to understand why cultural figures from our childhood promote feelings of well-being.

If we were fortunate enough to have a largely happy time, they remind us of the carefree days – before responsibility, before rain became a problem, before bills and taxes and car problems.

That’s why, above my desk, I have a Peter Firman sketch of each of the Clangers. That’s why, when I hear the theme from Play School, all I think of is Fuzzy-Felt and the playpark at the bottom of Longhaugh Road in Fintry.

The after-school TV experience was key in the era before piles of homework.

I could kick back after a hard day of sums and spelling with a peece and jam, and (thanks to those crafty TV makers) still be learning.

Blue Peter was OK, Magpie was hipster Blue Peter, but the pinnacle of educational kids’ telly was HOW, and at the helm was Fred Dinenage.

With his exuberance and animated presentation style, he was my favourite teacher.

This is how a gyroscope works, this is how a ship goes in the bottle, even how they make a very long egg.

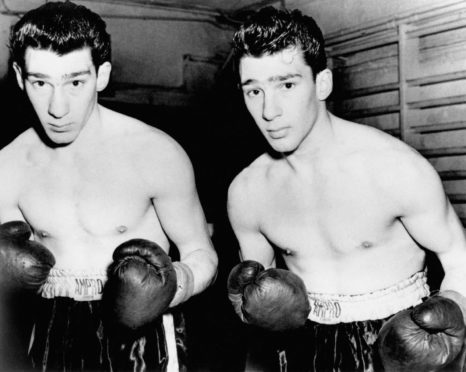

Not too long ago, however, I was channel-hopping late at night and there’s Fred, sitting in a typical London East End boozer, across the table from “Mad” Frankie Fraser, talking about “manors” and “shooters” and how the Krays loved their mum (something like that anyway). What? Surely this isn’t how to get rid of a rival gang?

It was part of his Murder Casebook series and, as it turned out he had ghostwritten autobiographies for the Kray twins. Suddenly he wasn’t my favourite teacher.

I wondered how he could justify making money from telling the stories of two horrific characters. Out and out bad ‘uns who have been sprinkled with more of that celebrity criminal fairy dust than most.

Who was next?! Brian Cant meets Charles Manson?

Of course we’ve always been fascinated with the macabre and the ghoulish. From thousands swarming around the site of public executions to centuries-old murder ballads.

Stories with extra bite

The fictionalisation of the mass murderer feels a little less obscene than the glorification of the real-life criminals.

As far as storybook baddies go, Dracula takes some beating. He began in fifteenth-century Transylvania with the barbaric, and real, Vlad III (or Impaler) and somehow ended up in Sesame Street as a purple puppet teaching children to count (ha ha ha).

In between there have been (and this is a far from complete list) Bram Stoker’s masterpiece of a novel, Nosferatu, a glut of Hammer horrors with Christopher Lee, Louis Jourdan in a 1970’s BBC version and, just last year, a new adaptation with the wonderfully named Claes Bang as the Count.

When it came to Dexter, adapted from the Jeff Lindsay books about the serial killer who only kills other serial killers, we were invited to sympathise with the main character.

He had been taught to channel his murderous instincts by his policeman father, tired of seeing killers go free.

I was certainly taken in by this and rooted for him at times, but whether that was more to do with Michael C. Hall changing into a pec-hugging T-shirt every time he killed, I wouldn’t like to say. Yes, yes, woman can be guilty of that too…

Don’t have nightmares

In the real world Crimewatch feels like a throwback now, where viewers are invited to do their civic duty and help catch the blaggard rather than salivate over detailed reconstructions.

Skimming through the channels of my limited TV package, there are so many digital offerings that offer nothing but murderous mayhem.

Of course they’re in competition and will up the ante in how they reconstruct crimes.

This leads to even the most eminent of criminologists making regular appearances.

It obviously lends the carnage some credibility, but even someone with the background of Professor David Wilson can present the crimes slightly too ebulliently.

Actors have also embraced the chance to play heinous individuals. From Maxine Peake as Myra Hindley to Dominic West as Fred West, to David Tennant as Doctor Who, sorry Dennis Nilsen.

Getting to the heart of the heartless

It’s something that can obviously prompt criticism, so there must a desire to get to the core of how people who look like us and to all intents and purposes live like us, but can commit such utterly repugnant acts.

We’re back to psychologists, who say that this fascination with the depths of depravity is nothing to do with our potential for evil.

It’s said that this is escapism, something that is so far outside of our understanding. It’s as unlikely as going to the Moon.

That’s all very well, but with TV schedules and bookshops and podcasts packed full of violent crime, it has to has an effect. You have to wonder if it’s bad for the soul.