Well, that’s summer here. Holiday season. Rain for what felt like the entirety of spring, then, as the Bank Holiday sun came out, the haar rolled in.

Even these recent fine days have had a scunner of a wind blowing across them, snatching the paper cups fae your hands.

A long summer holiday abroad would be absolutely fine right just now. A wee all-inclusive in Crete, or Turkey for example.

That’s off the cards, it seems. The Delta variant and all that.

So what has a stay-at-home holidaymaker to do?

Initially, I thought I might get innovative. I considered recreating my trips to Europe’s antique towns by taking a photo book of Rome and a few cauld tinnies into the sunbeds at Indigo Sun.

There, I could scorch myself scarlet and drunkenly misinterpret Roman archaeology at my leisure, just like holidays of old.

Licensing laws forbid, alas.

But we’re stuck here in Caledonia for the summer. And it’s easy to take that badly.

A rain-lashed week in the Red Lion at Arbroath with the same small family bubble ye’ve been imprisoned with for a year might no be the tonic ye need.

Albacatraz or a great escape?

Scotland might feel like a rainy prison island. A sort of Albacatraz.

But fae another perspective, this is a tremendous opportunity.

Scotland in summer is usually absolutely hoaching.

Tourists by the tonne, in campervans, in snaking lines at every ice cream shop, thrumming off coaches and through castles and cafes, Americans and Australians striding like a tide up the Royal Mile by the hundred thousand.

They are all very welcome. But they dinnae half jam up the bonnie bits.

Skye’s shoreline sinks inches lower into the sea under the sheer weight of sightseers. Nessie dooks that bitty deeper doon away fae the camera-clutching crowds.

Even normal stuff gets hassle. Ye can barely get a coffin buried in a graveyard or a wedding procession done in July without a knot of visitors digitally documenting it.

Not now though.

Scotland is, for this summer alone, ours.

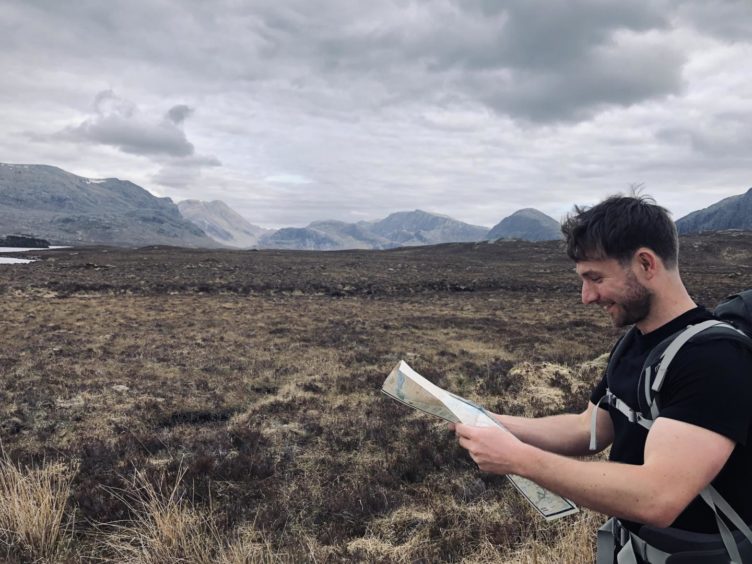

I cycled a wee stretch of the North Coast 500 the other week.

I’ve been up there a few times before, and things are drastically different now.

Generally, I pass half my time with my mouth agape and my heart hammering joyfully as the landscapes and life exhilarate me.

The other half of my time is spent gesticulating feverishly at a European campervan as they engage me in a game of Chicken on the single-track road.

Passing Places dinnae seem fully understood by our continental sisters and brothers.

This time though? I was just aboot alone on the road.

I could zip round potholes, slalom through suckling lambs and weary-eyed ewes as they warmed on the damp tarmac.

Across the horizon was slung one of the most distinctive mountain ranges in Scotland; the hills of Assynt.

Poet Norman McCaig immortalised the view, calling it a “frieze of mountains, filed on the blue air.”

It’s as different to Dundee as you need it to be on a holiday. It’s as foreign to the Ferry as the Tatras in Poland, or the forests of Latvia. You’ll come away utterly refreshed.

But there’s way mair on offer out there in our hinterland than just a bit of peace and quiet.

There’s something older, deeper and more meaningful.

The Gaels of Scotland have a concept called Dulchas.

The Gaelic dictionary gies its meaning as Heritage or Tradition. And that’s part of it, but it goes beyond that.

It belongs to us and, as importantly, we belong to it

It’s partly the stuff we inherit from those that’ve gone on. But it’s also a binding between ourselves and our place.

Dulchas is the idea that belong to this land, we’re custodians of it. It belongs to us and, as importantly, we belong to it.

This sense of a shared fate between ourselves and the earth beneath us was earned over millennia of symbiotic coexistence.

Dreils scraped out on dreich hillsides, stane quarried, kelp collected. This landscape sustained us, and we in return did our best to care for it.

It was this sense of belonging that infused such sorrow into the Clearances.

The old understanding between folk and their place broken, as they were ushered from their homes to newbuild towns. The Iron Age continuities were broken.

I think it’s the same sense of attachment and love of land that McCaig was exploring in his Assynt poem, too.

“Who owns this landscape?

Has owning anything to do with love?

For it and I have a love-affair, so nearly human

we even have quarrels.”

I cannae pretend I have the same familial relationship with the land that the ancestors did.

My Grand Granda that ploughed on Deeside, and my Great Granny that worked on a farm on Arran likely understood the earth in a way my iPhone-clutching townie self never will.

But like McCaig’s poem I’ll explore and I’ll question and I’ll linger in the outdoors.

I’ll turn this summer of hemmed-in horizons into a chance to go deeper into this place that sustains us.

And as we pivot into a lower carbon future, I’ll be spending a lot more holidays here at hame.

I accept that Scotland maybe cannae offer the amber-skinned exoticism of Slovakian lakes or mesmerising bafflement of a packed Istanbul.

But as I slam shut the laptop this summer and make for the wide-open spaces, I’ll be looking beyond the astounding views and beautiful birds to something longer lasting.