One of the first protests I ever took my daughter to was held in Glasgow’s George Square.

On a sunny afternoon, we gathered along with hundreds of others to voice our opposition to the UK government’s plans to limit universal credit and tax credits to only the first two children.

It was a proposal that poverty and children’s welfare charities had said would be devastating for low-income families.

The crowd that had assembled to protest that day was comprised of men, women and children; campaigners and a cross-party group of politicians.

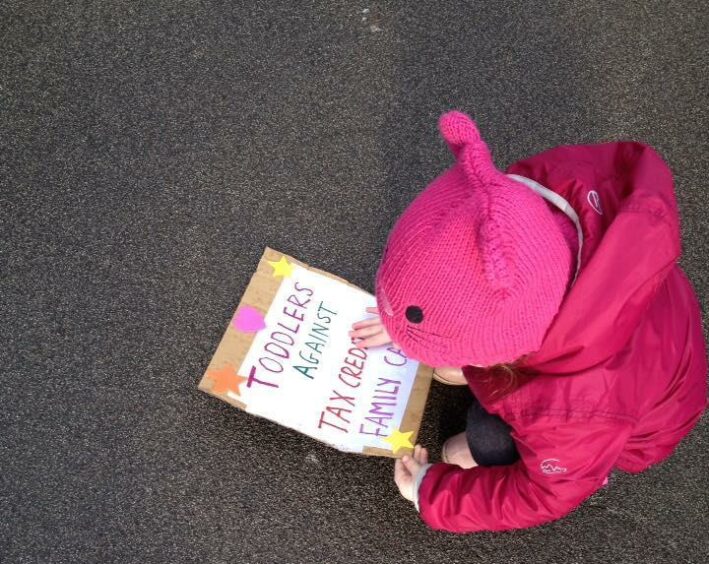

My daughter didn’t understand the purpose of us being there, but she was happy to be doted on by the friends we bumped into and she held up a sign that we’d made that she couldn’t yet read, which said: “Toddlers Against Tax Credit Cuts”.

From the two-child cap flowed a putrid necessity that we now refer to as the rape clause.

This is an exemption to the cap which means that women can access support for a third child, providing she submits the required paperwork to disclose that the child was conceived through non-consensual sex, i.e. – rape.

Rape Crisis Scotland representatives spoke at the rally that day, highlighting the cruelty of forcing women who have been through the trauma of rape to reveal that fact to officials so they can feed and clothe their children.

They spoke of the danger too: many women who qualify for the rape clause exemption are in abusive relationships.

Requiring them to tell a third-party about their circumstances could be a risk to their safety.

The proposal became policy and every year we see numbers that give a grim insight into its impact.

‘Don’t think small number is an insignificant one’

Figures published last week showed that since 2019, there has been a 160% rise in the number of women who have had to reveal that their child was conceived through rape in order to access certain benefits for that child.

By April this year, the figure had risen to 1,330.

We should not confuse that relatively small number for being an insignificant one.

Every one of those 1,330 women has been through a horrific ordeal and the UK Government’s punitive benefits cap has only added to their trauma.

I wonder if Conservative party politicians and representatives have spent much or any time this week considering those 1,330 women.

Have they allowed themselves to dwell, even for a moment, on how it must feel to be faced with such a terrible choice?

To choose between your autonomy over what traumatic aspects of your life you are willing to share, or to forgo your privacy to access the money you need to support your children?

Inhumane policy

What that number doesn’t tell us is how many women didn’t – or weren’t able to for fears for their safety – claim the rape clause exemption.

The tentacles of this inhumane policy reach even further.

The British Pregnancy Advisory Service (BPAS) says that a growing number of women are terminating wanted pregnancies because they fear the cap means they wouldn’t be able to support those children.

BPAS chief executive Clare Murphy highlighted this worrying trend.

She said: “Since the policy was introduced, the number of abortions among women with two or more existing children has risen by 24%, compared with an increase of 11% among women with one existing child.”

Two main defences: fairness and cost to taxpayer

Those who seek to defend the two-child cap and associated rape clause usually put forward two main arguments.

The first is one of fairness. They say that those who are not entitled to in or out of work benefits have to make decisions about the size of their families based on affordability, and so too should low-income families.

The second argument centres on the cost to the taxpayer.

The Child Poverty Action Group says that removing the two-child limit would cost £1bn and doing so would lift 200,000 children out of poverty and 600,000 children out of deep poverty.

It seems that the UK Government don’t think that this is a price worth paying.

Both of these arguments rely on a shallow analysis of the role and purpose of social security benefits. It is an argument without nuance, deliberately so, because the “shirker and scrounger” myth is compelling to many.

It glosses over the realities and unpredictability of life and the impact bereavement, separation, illness, redundancy and everything in-between can have on even the most well thought-out attempts at family planning.

‘Defence of the indefensible’

This defence of the indefensible asks us to put aside everything we know about the conduct of the UK government during the pandemic, which has been characterised by a reckless indifference to how tax-payers money has been spent, often in a way which has benefited Tory party friends and donors.

It’s hard not to think of those 1,330 women when we read stories of yet another misuse of tax-payers cash.

I suppose, in the end, it all comes down to priorities.

Those that seek to defend a policy that has a detrimental impact on low income families and that holds children in poverty might think they know about the value of money.

But they know very little about the value of anything else.

For more by Kirsty Strickland:

- KIRSTY STRICKLAND: Isolation of ‘chancer’ Boris Johnson on England’s Freedom Day is almost poetic

- KIRSTY STRICKLAND: England fans are sticking flares up their bottoms, personal responsibility for Covid masks feels like a stretch

- KIRSTY STRICKLAND: Tom Kitchin says emotions run high in kitchens? Give us a break – it’s squid-ink pasta, not intensive care