On Monday November 19, 2001, Afghan women were welcomed into Downing Street. Twenty years later they’ll be lucky to escape Kabul.

Fleeing Afghanistan in such a rush means we betray an original principle of the invasion.

We went in not just to hunt Osama Bin Laden, but to modernise Afghan society.

That this became an afterthought in our departure is an indictment of all the allied governments.

After 9/11 we were told radicalised Saudis had carried out the attack, led by the Saudi Arabian cleric Osama Bin Laden.

We were also told Saudi Arabia was not our enemy, but Afghanistan was because it was home to terror groups.

An allied invasion was proposed and public opinion was divided.

America’s military was clearly superior to everyone else’s, but its role as global policeman was questioned.

A doubt that began in the 1960s with the Vietnam war had become fixed in the public mind.

Recent conflicts cemented those doubts

The first Iraq war of 1990 had been a military success but it had the whiff of pointless gesture. Saddam Hussein was still in power.

When President Clinton sent troops into Somalia, they were televised arriving on the beach live – American power appeared more entertainment than risk.

The Balkan wars of the mid-1990s had shown that allied military intervention could be spectacularly inept.

Given the Soviet Union’s decade-long failure to suppress Afghanistan, invading seemed foolish, even if it did catch the bad guys.

The Blair government was divided on the matter and American public opinion was unsure.

Then the plight of women was introduced.

Women as PR weapon for Afghanistan war

The US president’s wife Laura Bush took over her husband’s weekly radio address to speak about how women were denied liberty and education under the Taliban.

A week later, Cherie Blair invited Afghan refugee women into Number Ten.

She spoke with fervour at the event, according to reports.

Impassioned by the miserable lot of women under the Taliban, she hinted it was our progressive duty to free them from religious fanaticism.

This message was echoed by the next speaker, veteran left wing figure Clare Short.

Short was becoming a martyr for peace and politically Tony Blair had to win her over if the government was to appear united.

The condition of women was the issue which brought her round.

Culture idealises the sacrifice of the men and forgets about the women. To highlight the condition of women in the Taliban regime seemed new and right

It was novel then to cite the treatment of women as a reason for war.

Wars are when young men get shot and women are raped.

For centuries, culture idealises the sacrifice of the men and forgets about the women.

To highlight the condition of women in the Taliban regime seemed new and right.

It also seemed essential.

How could the UK and America, happily enjoying boom years and third way politics, not oppose the misogyny of the Taliban?

When Tony Blair first announced British involvement with the US in Afghanistan in October 2001, the humanitarian aspect was already part of the war’s purpose

“We have to act, for humanitarian reasons to alleviate the appalling suffering of the Afghan people, and to deliver stability so that people from that region stay in that region.”

Original mission at odds with departure

This became central to the allied occupation of Afghanistan.

Over 20 years our troops have protected all manner of educational and cultural projects which have transformed conditions for Afghan women.

The sacrifice of soldiers’ lives was in the name of progress. That was a noble cause.

Yet our departure was framed entirely around military concerns, costs and the public weariness with forever wars, in president Biden’s phrase.

Four presidents have presided over an American troop presence in Afghanistan—two Republicans and two Democrats. We will not pass this war onto a fifth. pic.twitter.com/d5kIcw27h8

— Joe Biden (@JoeBiden) August 17, 2021

In truth, Afghanistan had ceased to be a war. It was an intervention which protected the human rights of Afghans and which, as stated by Tony Blair, controlled a refugee crisis.

Our departure takes Afghanistan back to where it was. Refugees, rapes and oppression.

To present this, as western governments have, as an unfortunate side effect of a military exercise is to wilfully distort history.

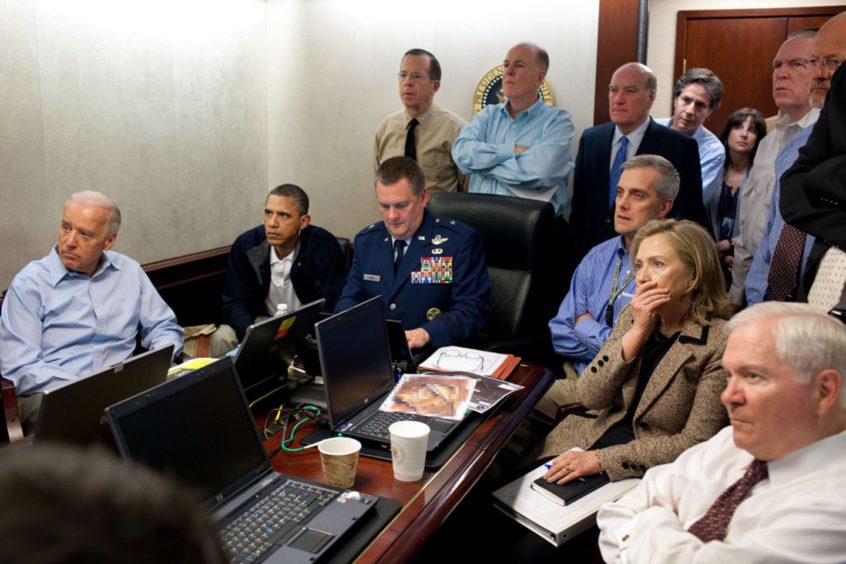

We had a mission to help. Everyone knew this, or we would have withdrawn in 2011 when Bin Laden was killed.

We stayed another 10 years to honour the mission.

In quitting now, we dishonour ourselves.

What now for women of Afghanistan?

Defence minister Ben Wallace says that once America decided to go, European governments had no choice but to follow.

He broke down in tears on Monday as he acknowledged the consequences.

Not to question his sincerity but we are entitled to wonder why he and others didn’t do more to promote the original motive of the war.

Where were the Downing Street receptions for Afghan women in 2021?

Boris Johnson appeared to rule out the prospect of an independent formal inquiry into the UK Government’s conduct in Afghanistan yesterday.

But in July he told the Commons: “In the unforgiving desert of some of the world’s harshest terrain – and shoulder-to-shoulder with Afghan security forces – our servicemen and women sought to bring development and stability.”

They succeeded in their mission. It’s the politicians who failed.

It is a scar on the conscience of Europe and America.

Britain had 750 troops in Afghanistan in July of this year. American forces amounted to 2,500.

Combined, they protected 38 million people, including a generation of girls who had grown up free to play and go to school.

We wish them luck, and our regret.