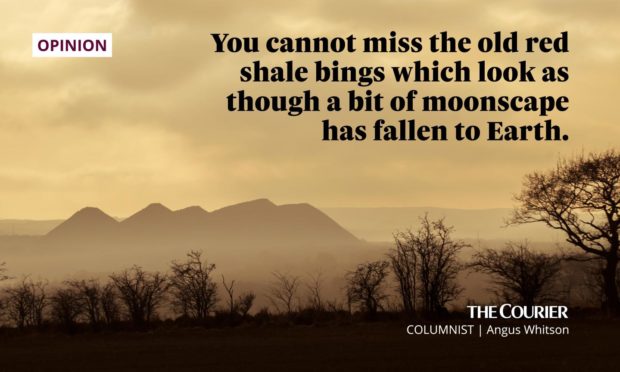

Driving into West Lothian over the Queensferry Crossing road bridge, you cannot miss the old red shale bings which look as though a bit of moonscape has fallen to Earth.

Catch them with the low late-afternoon sun on them and they look tinted rose-gold and positively ethereal.

The hard reality is that they are spoil heaps – spent ash waste – from the oil shale mining industry which operated for some sixty years from around 1860 and can arguably be regarded as the forerunner of Scotland’s oil industry.

The famous James “Paraffin” Young discovered a method of extracting oil and paraffin – hence his nickname – from the shale.

He founded an enormously successful company which for a time was responsible for lighting almost the whole of London before electricity provided a cleaner method of illumination.

The mined oil shale was taken by barge from Port Buchan to Paraffin Young’s refinery in Bathgate for processing.

James Young, who discovered paraffin oil, born Glasgow #OTD 1811 #wesaluteyou #GoIndustrial pic.twitter.com/ZCHdKhwmuB

— Go Industrial (@GoIndustScot) July 13, 2017

The old red shale bings are of interest to a nature writer like me because, since the industry finally closed in the 1950s, the bings have gently – unnoticed almost until recently, you might say – returned to nature without any assistance from us humans.

Birches and alders and hawthorns have taken root in the red “blaes” as the red slag is technically known, though it’s surprising there’s enough nourishment in the rocky surface to sustain them.

But nature is very determined when she sets her mind to something.

Shale bings are a rich habitat

Grasses and dozens of wildflowers now flourish where none flourished before, and hares and foxes have made their home there.

You’ll find butterflies, bees and moths and numerous species of insects.

Bird life is abundant and in the spring the skylarks’ glorious chorus can be heard cascading from the sky.

Driving into Edinburgh I’ve seen three buzzards lazily circling high in the sky above them, patiently waiting to spy a young rabbit or a field mouse foolish enough not to keep to the meagre cover available.

And all this from scratch, from the most unpromising beginnings.

So successful has regeneration been that the part known as the Five Sisters has been given scheduled industrial monument protection.

With the initial shock of the shale industry finally closing there was local resentment at what were perceived to be nothing more than unsightly spoil bings, reminders of an industry gone bust and employment gone with it.

But over time the strange red hills have become a distinctive feature of the West Lothian landscape.

Barren wastelands have turned into islands of wildness in a predominately agricultural landscape

With unobtrusive wilding – as wilding should surely be – left to themselves the bings have experienced a natural restoration, creating new habitats for wildlife.

What started as barren wastelands have by sleight of ecological transformation turned into islands of wildness in a predominately agricultural landscape.

Take a longer look at the old red bings the next time you pass that way.

Stumped by the swallows

Being The Courier’s Man with Two Dogs sometimes carries a heavy responsibility.

From time to time I am called on to explain some natural phenomenon or animal behaviour and I find myself admitting I don’t have an answer.

A reader called to say that the swallows that had been nesting in her eaves had disappeared overnight, presumably started on the arduous flight back to their Southern African winter quarters.

From past years’ experience it was at least three weeks earlier than she expected.

She hadn’t even seen them gathering on the telephone wires, coffee shopping amongst themselves, discussing just when they should be on their way. Did I have an explanation? No, I did not.

We agreed it couldn’t be lack of food for I’ve been watching the graceful, agile birds swooping over the fields of barley and coursing over the surface of my secret ponds in pursuit of flying insects to feed their late broods of chicks.

The pair that rebuilt the nest that fell from our eaves appear, from the activity in and out of the new nest, to be feeding chicks successfully.

At school we had a biology master who dismissed any question he couldn’t answer, with – “Sometimes we have to say, we just don’t know.”

I guess I fall into that category.