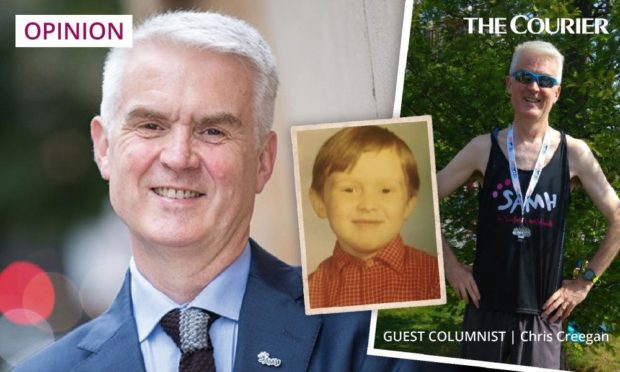

In 2013, I joined the board of SAMH – the Scottish Association for Mental Health. Two years later I became chair.

This month I step down – my time is up. Good governance demands it. But it will be a wrench. There is still so much work to do.

When I took on the role, I went public about my own mental illness, in particular a depressive episode which had culminated in a suicide attempt in my early 40s.

It felt right, given the scale of the responsibility I was embarking on, that I should bear witness to my own experience.

But in truth that experience predated my midlife freefall by more than three decades.

When I was five, my mum had what we used to call a nervous breakdown.

It wasn’t the first time it had happened since she and my dad had adopted me as a baby in 1961.

Nor was it the first time either she, or we (my sister and I), had been sent away as a result.

But it was the first time it had a name – and a place – attached to it.

I only dimly remember that place, a sprawling Victorian mental asylum, on the outskirts of Manchester where I grew up.

My memories of the consequences for me and my siblings and our daily lives are altogether more textured, vivid even.

Though just as mum’s condition was shuttered away, our experience remained largely unspoken – except by us – until much later.

In time – and perversely not unrelated to her illness (people thought having more babies might somehow cure her) – I became the eldest of five.

The silence which cloaked our ordeal was despite the fact that the phrase ‘hidden in plain sight’ could scarcely do justice to the obviousness of her plight, let alone ours.

Mental health and my own adulthood

Mum died the year after I joined SAMH. But the legacy of her illness during those years lives on in us in myriad ways.

While still at primary school, I would return home to find her weeping over a cold grate.

As I tried to make it right, I would reflect on the seeming waste of her life and hope mine wouldn’t turn out like that.

Though depression was a feature of my life from adolescence, I mostly held it together until that midlife crash.

When it came it was a product of many things – personal and familial, just as I came to understand mum’s experience had been.

I too found myself incarcerated (albeit at my request initially) in an overcrowded Victorian mental institution in London’s east end.

My subsequent suicide attempt, on a trip to Edinburgh the year before I moved here in 2003, was an experience whose stigma clings to me still.

Talking about suicide is never easy, but taking the time to ask someone how they are feeling could help to save their life.

Our ‘Suicide…How to ask?’ card is a simple, step-by-step guide to asking someone if they’re thinking about suicide: https://t.co/cpcg6E7lYV pic.twitter.com/tu1jOtUndN

— SAMH (@SAMHtweets) August 22, 2021

Recovery was a trudge not a revelation. Setbacks still happen.

Lived experience has become Scottish social policy mantra this last decade.

And yet you may still be wondering why I am telling you all this, especially now just when I no longer need to authenticate my credentials.

The answer is this. However unique my story is to me; it is commonplace too.

Such stories are no longer the preserve of one-in-four, a phrase I used myself just six years ago.

Each of us has a mental health story.

And while mental illness is no respecter of social and economic markers, if you are poorer so, all too often, is your mental health.

Adults living in Scotland’s most deprived areas are twice as likely to have mental health problems as those in the least deprived areas.

Thankfully we now talk openly and often – if not often enough.

But our ability to acknowledge our mental vulnerability has not yet been matched by our response to it as a society.

Mental health is an emergency

Two decades of strategising have left us more informed, more articulate about mental health.

But the much-vaunted ambition of parity of esteem with physical health remains a pipe dream in anything other than aspirational terms.

Investment and implementation lag behind. The cost racks up – in rising waiting times and, tragically, lives lost to suicide.

Covid-19 just compounded the task we face to put this right.

And as SAMH’s research shows, whatever the impact on the general population, it is those with pre-existing mental health problems who have been hardest hit.

Over half of participants in our November 2020 survey felt their mental health had worsened during the pandemic.

Yet they could not rely on getting the support they needed.

As I step down from SAMH’s board, I leave an organisation more determined than ever to play its part.

We are fortunately not alone. Indeed, ours is a cause du jour.

But as decades of debate about climate change have shown, talk is easy. Action is much, much harder.

Yet we have no more time to lose – mental health is an emergency.

And it’s about far more than fixing a system. It’s about changing a nation.

Chris Creegan is a consultant and writer living in Edinburgh. He is the outgoing chair of SAMH whose board he joined in 2013.