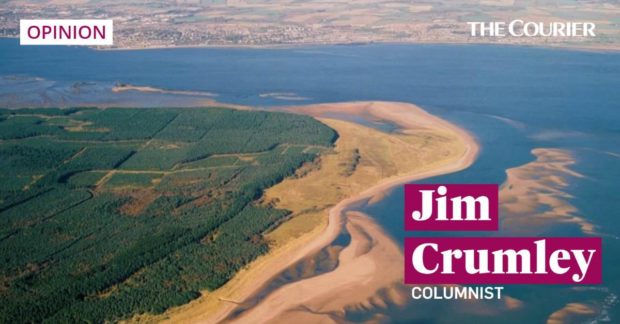

The lure of the unexpected is what haunts Tentsmuir.

Step from the pines and through a slender screen of alders, thread a path through the dunes and finally confront the triple expanse of open sand and open sea and open sky arranged in immense horizontals.

Mercifully, I never learned to grow indifferent to the moment, never failed to thrill to the way it stops me in my tracks.

Ever since the notion occurred to me a few years ago now that it looked like a tricolour, nature’s national flag, it falls into place again every time.

A lot of my notions in nature’s company are just plain daft: that’s one that I like.

I went from there to imagining someone like the Russian-American painter Mark Rothko (1903-1970) confronting that same moment of revelation for the first time and thinking to himself:

“No, I need bigger canvasses for this, much bigger canvasses.”

And he filled them with horizontal bands and slabs of colour, some dramatically contrasting and others subtly blending one band into another, just like the landscape before his eyes at sunrise or dusk.

As far as I know, he never stood atop the seaward edge of these particular dunes and had his mind blown.

But he was one of the New York School and he had the western edge of the Atlantic Ocean at his disposal, so he would have felt quite at home.

He was famously reluctant to explain what motivated his huge abstracts.

And perhaps reading them as land-and-sea-scape is too simplistic.

But they are there in my mind anyway and Tentsmuir is their symbol.

Putting Tentsmuir into words

I read a review of a retrospective of his work at the National Gallery of Art in Washington a few years ago.

And I circled a passage which, despite the academic tenor of the writing, corresponds to the kind of thing that crosses my mind when I step out on to Tentsmuir beach:

“Absolutely radiant and dark, Rothko’s art is distinguished by a rare degree of sustained concentration on pure pictorial properties such as colour, surface, proportion and scale, accompanied by the conviction that those elements could disclose the presence of philosophical truth.

“Visual elements such as luminosity, darkness, broad space, and the contrast of colours, have been linked to profound themes such as tragedy, ecstasy, and the sublime…”

And, yes, feel free to wince at the language – I did. But I can see where the man is coming from.

For although I wasn’t within 3,000 miles of Washington at the time of the exhibition, I do have a highly prized copy of the catalogue of a Rothko show at the Venice Biennale a few months after his death in 1970, and the meticulously printed images in it scream Tentsmuir to me, page after page.

It was a gift from a great friend – George Garson, mosaicist and stained-glass artist who had his own department at Glasgow School of Art.

George died in 2010 but lives on in me in many ways, and among countless other gifts, his friendship taught me ways of seeing nature that would never have occurred to me otherwise.

The very weekend that has just marked 20 years since the attack on the Twin Towers also marked 30 years since George handed me the Rothko catalogue.

He had brought it back from the exhibition in Venice.

Tentsmuir and its autumn attractions

My nature writing life has been enriched by friendships with artists, and still is.

Autumn seems to intensify it for reasons I don’t fully understand, although it was always my favourite season of the year.

Autumn is getting closer! #Tentsmuir is a great place to find a wide range of incredible #fungi. These species were seen there recently: Turkey-tail fungus growing out of a rotting log, puffball fungus on a grassy path, and a beautiful cup lichen out on the dunes!

@BritMycolSoc pic.twitter.com/i57rZWOmO4— ForthNatureScot (@ForthNatureScot) September 3, 2021

And Tentsmuir certainly comes into its own in autumn as legions of wildfowl drift down the country and the North Sea from Greenland and Iceland and Scandinavia and thicken the tideline, and the grey seals steam into breeding mode.

So I followed accustomed paths and stepped from dunes to beach and raw space came at me in waves.

It was an almost physical force whose characteristics were as Rothko insinuated, “colour, surface, proportion and scale”.

It is not just the sunrise that distinguishes east coast beaches from those on the west coast, there is also that conspicuous lack of islands.

The sense of proportion and scale is overwhelmingly intensified by the absence of a focal point.

Pale tawny sands (the light paints them variously from almost grey to gold to almost orange at sunrise) run away from you across immense distance to south and north, and as far east as the lowest of low tides permits.

And the sands darken by degrees as they march eastward towards the sea’s white edge.

The sea in the morning is electrified by sunlight.

There is almost too much light.

I decided to walk out to the edge of the sea and then walk north to look for seals and sea eagles, knowing that if I did, and whether I saw seals and eagles or not, all kinds of other things would cross my path.

I knew that because a lifetime in this place has taught me that they always do.

The lure of the unexpected haunts Tentsmuir still.