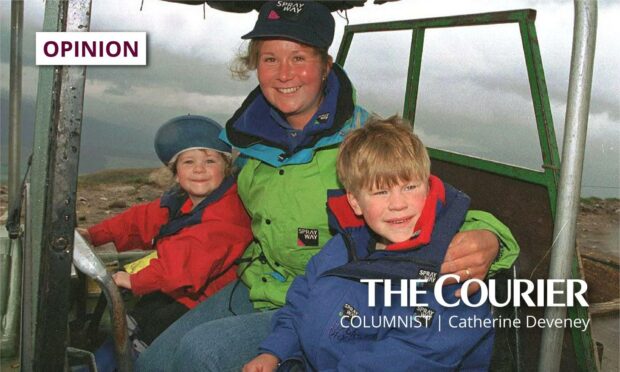

Early in my journalistic career, I was sent to Fort William for the triumphant return of Alison Hargreaves, the first woman to scale Everest without oxygen.

At the top of Aonach Mòr, her daughter Kate, a little mini-me Alison, ran excitedly around her, while her six-year-old son, Tom, hung on her arm as she tried to dip her spoon into soup, unwilling to let her go.

They were poignant memories when watching this week’s new BBC documentary, The Last Mountain. Alison died on K2 just weeks later, while Tom died almost 25 years on, attempting an unconquered – some say suicidal – route on Nanga Parbat.

The bodies of mother and son lie unrecovered on the slopes of the Himalayas. “Your mum’s spirit is in these mountains,” Tom’s father, Jim Ballard, told him as a child. Maybe that drew Tom’s spirit there, unwilling still to let go.

Preparing for loss for a long time

Jim was criticised back then, mostly in behind-the-hands comments about his “composure”. Too much sang-froid for those who preferred their grieving widowers with wet hankies. He knew that if he cried a bit for the cameras, people would like him more. He wouldn’t play that game.

“Before a major climb,” he told me at Aonach Mòr, “I have always worked out the scenario for her paying the ultimate price. I think it’s just common sense. Life goes on and if I am left here to run it without Alison, I have to have thought about that.”

The new film captured the moment Kate phoned him to tell him about Tom’s disappearance. Some viewers might have found his quiet composure – that word again – almost disturbing. Yet, there was a depth of sadness, and a level of resignation, in his eyes that suggested this was not the first time he had faced losing his son.

It looked like Jim had been preparing for this moment for a long time. Kate, on the other hand, was broken, displaying all the familiar signs of grief: anger, fear, a refusal to accept. Watching her, Dylan Thomas sprang to mind. Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

It was Kate who, for me, illustrated one of the lessons of this tragedy. Photo footage had captured both Alison and Tom ascending rockface like lizards. Not “conquering” it but uniting with it, like they were an integral part of the landscape.

Admirable qualities can become cruel masters

Kate, too, loves mountains. She feels her mother’s presence when climbing. But it was Tom, she thought, who got all her mother’s ability. Tom who was driven and focused and determined.

“In teenage years, I was jealous of how talented he was, of his passion,” she acknowledged. “For Tom there was one thing, mountaineering, and that I envied – because he just knew.” But it is Kate who is still alive.

For all of us, the need to succeed can sometimes be self-destructive

I realised, hearing her words, that I have always admired the qualities Alison and Tom displayed: tenacity, courage, focus, drive. But those qualities can become cruel masters. Tom’s death was uncannily like his mother’s.

Alison’s climbing partner on K2 survived. He and Alison had temporarily swapped climbing partners within their group. He had summited; Alison hadn’t. The weather window was lost and Alison was due to return home, but she changed her plans last minute, staying on for one last attempt. Tom, too, remained when others turned back.

For all of us, the need to succeed can sometimes be self-destructive. We each have our mountains to climb, but refusal to adapt our drive to our circumstance can be – physically or emotionally – lethal.

Women can be what they want

Alison left silk flowers on the summit of Everest for the dead climbers she had passed on the way up, those whose bodies lay forever now on rock and ice, in swirling snow. A tender gesture of recognition for strangers who could so easily have been her – and would become her.

She was criticised back then because she was a mother putting herself in danger, but I admired Jim Ballard’s rebuttals, his insistence that a woman could be what she wanted to be. Why should it be different for mothers than fathers? But those words were the words of a husband, an equal.

How hard it must have been for Jim as a parent, a guardian, to keep his promise to Alison that their children would be encouraged in outdoor pursuits. How hard to watch Tom become a successful – and driven – climber like his mum.

“I am glad Tom and my mum are here,” Kate said tearfully on camera. “It’s the most beautiful place on earth and it’s where they wanted to be.”

Kate clearly thought of herself as less gifted than Tom. Perhaps she was just more balanced. For all her teenage admiration of her brother, perhaps it was she who received the greatest gift after all.

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter