My car’s been in the wars. And I’ve learned something really unpleasant about where I live. Maybe you’ve noticed it already, but I hadnae.

I’d had a meeting in Costa Montrose then done some work on the laptop.

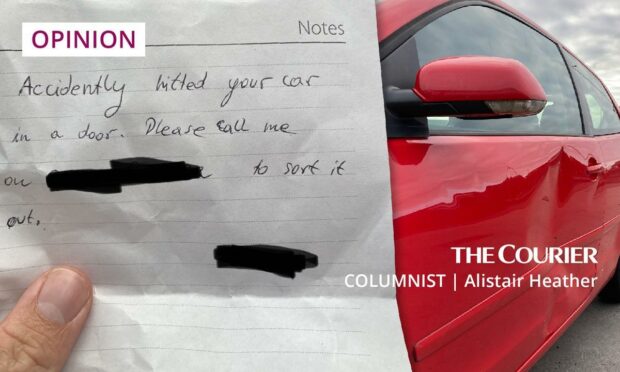

My wee red VW Polo was safely stationed outside.

Meeting concluded and the pleasant background natter of a smalltown Costa winding down towards the close of day, I packed up my gear and headed outside.

I was in the car, engine started when Pavol (not his real name) came belting across the car park to wave frantically at my windscreen.

I got a bit of a fleg.

He was muscular, overweight, and covered in splatters of paint. His eyes were wide in the heat of some intense emotion.

I got out.

“I’m sorry, I’m hitting your car, I’m hitting your car, I no see it, and *bash* I am hitting it,” he said, fashed.

I came round, palms out and down, giving him the universal human hand gesture for “simmer doon pal”.

He led me round to the passenger side of the Polo, and showed me he had crashed his car into the side of mine, somehow.

He’d absolutely battered into it, to judge by the dent. If moved to the horizontal plane, it had enough volume to double as a kids paddling pool.

Pavol was in a flap.

His partner was sat in their car, looking pretty sheepish.

“Hey pal, really, it’s not a big deal,” I tried to explain.

Which is true. The car cost £900 and came pre-scratched and dented.

It was and is a midden of a vehicle. An automotive student flat. I tried to impress this upon Pavol, but he remained up to the highest of does.

And that’s where the story starts to get a bit sad. Although I didn’t clock it at the time.

Out of the way of officialdom

Pavol pleaded not to involve insurance companies. He also asked not to call the polis.

I was completely fine with the former, as I dinnae enjoy admin.

And the latter, I dinnae even think the polis get involved in minor prangs anymore.

Instead Pavol insisted on giving me £300 cash in hand.

That seemed steep for a repair to a lemon, but whatever.

We drove in convoy to a cash machine.

Pavol remained frantic, bouncing out his car, door agape, hurtling to the cash machine and button-bashing hard enough to give the ATM CPR.

I joined him.

He didn’t have £300 in his account. He had a bit less, but he took it all out – cleaned out his account – and handed it to me.

Obviously – OBVIOUSLY – alarm bells should have been ringing.

He gave me £270, and his partner was going to take out the extra £30 and give me it but I felt well enough remunerated and left.

I went off with my dunted heap and thought no more about it.

And then the Brexit penny dropped

It was my pals that kicked up a fuss.

Pavol – they said – was either without insurance, or without the right to work, or both, or else in some way was desperate to stay off the radar of the authorities.

That would explain his real terror at the incident.

It would explain the pocketful of notes he so happily handed over. More buying silence than paying for damage.

I reflected.

Pavol said he’d lost a few jobs recently but was ‘self employed’.

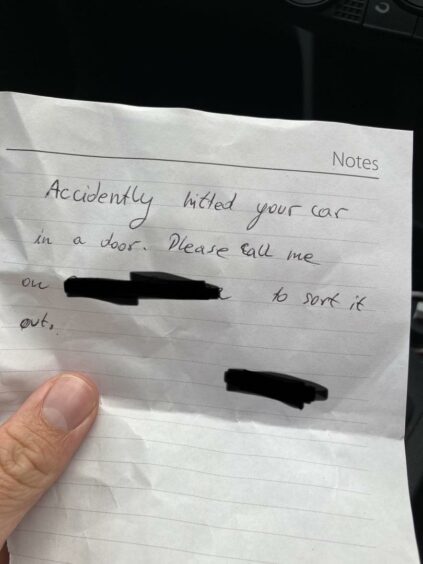

He’d been here six years, and was 26. His English wasnae great, as the note he’d already left under my windscreen wiper revealed.

He’s one of the people we’ve stripped of their rights and sense of security since we voted for Brexit.

Nae danger Pavol’s been on the innumerable complex websites required to get his Settlement Scheme application sorted before the deadline.

Also nae danger has he kept in touch with the Citizens Advice Bureau about his rights.

He’ll likely be relying on that go-to for migrant communities: hearsay, rumours and tangled news from the grapevine.

Brexit has left divisions and vulnerabilities

Our clumsy, ill-communicated and febrile departure from the European Union has created a distinct and vulnerable second class of citizen.

They are our pals sometimes, our neighbours at others.

Occasionally they are strangers who skelp into our motors then skint themselves handing over hush money.

Some of you will be happy to see your Pavols chased away.

Poles, Lithuanians, Estonians; they found their share of detractors in Angus and Dundee.

I dinnae agree.

As Ghandi said “the true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most vulnerable members”.

My bash with Pavol revealed to me how we’ve made a whole new tranche of folk vulnerable.

People like Pavol wouldn’t have been vulnerable in 2012. Now he is.

So by Ghandi’s formulation, we can judge Brexit Scotland by how well we treat this new second-tier of inhabitants.

To judge by the fear in Pavol’s eye, we’re not excelling yet.