I was on the Stansted Express when Noel Gallagher sent a text to say David Bowie had died.

It was January 10 2016, two days after Bowie’s 69th birthday, a day which had also seen the release of his album Blackstar to universal acclaim.

None of us knew those seven songs were Bowie saying goodbye to the world.

His death – so sudden, so unexpected and so private, at first felt like a cruel conceptual joke from an artist who thrived on the tension and drama of performance.

Bowie was a master – THE master – of blurring the lines between art and artifice. So much so that real life simply disappeared when you listened to him or saw him.

This is the outlaw who brought Jacques Brel’s raw, haunting My Death to the pop masses and who would regularly feign onstage collapse at the climax of his song Rock n Roll Suicide.

All this at a time when his contemporaries, the bricklayers in makeup, were desperately trying to hide their heteronormality in Max Factor and cheap glam stomp, glorious as that was in itself.

Ahead of the curve and an inspiration to kids like me

Bowie announced he was gay on January 22 1972 and changed everything, for me and for my generation.

He was always ahead of the curve in those early years.

Welcome to 2022 the year that marks 50 years since the arrival on Earth in 1972 of a certain alien rock god going by the name of Ziggy Stardust, more of that later. A Happy New Year to all, stay tuned for more leading up to January 8th and what would have been DB’s 75th birthday. pic.twitter.com/a0GIX8C0Wt

— David Bowie Official (@DavidBowieReal) January 1, 2022

Throughout his career he would explore the fragility of life either in his music or his lifestyle, often pushing himself close to the edge of survival.

This extraordinary sense of exploration spawned some of the most amazing records ever made by a contemporary artist.

And they just kept coming.

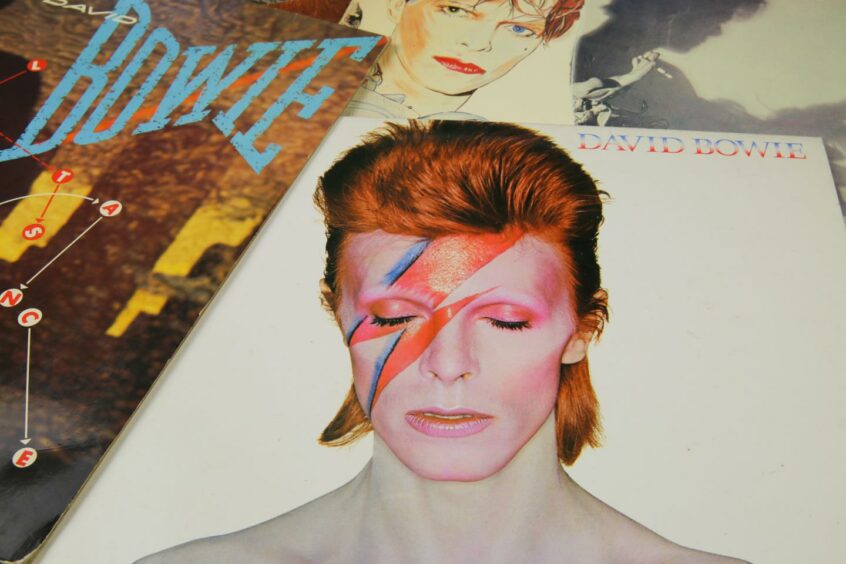

In the space of five years, we were swept from the era-defining glam rock of Ziggy Stardust through the transatlantic bewilderment of Aladdin Sane, the apocalyptic dystopia of Diamond Dogs, the beautiful soul of Young Americans, the drug addled paranoia of the Thin White Duke to the Berlin new age experimentations of Low and Heroes.

That’s some journey for one man to make, and for the fans who went with him.

I undertook much of this journey from my tiny bedroom in our council house in Granton Place, Dundee.

I had no money and no life but Bowie taught me that imagination is often the greatest asset we have.

He allowed us to enter a new world where Oscar Wilde dined with Jean Genet, where the Velvet Underground wrote with Kraftwerk and where it was better to risk temporary loneliness and alienation than be a reactionary old straight.

This is something I still feel today.

A letter that changed everything for this council house kid

At the age of 62 in a sense I’m still one of Bowie’s children.

Because he evokes in me a sense of otherness that helps make sense of the more ridiculous aspects of life.

Right from the start Bowie seemed to come from another universe, one so far from the mundane it transcended normality.

In the 1970s we needed that badly because normality was a brown and beige bore.

His blurring of artistic, social and sexual boundaries taught a generation how to pose with absolute conviction.

As an androgynous 13 year old growing up in a council house in Dundee this seemed inordinately thrilling to me.

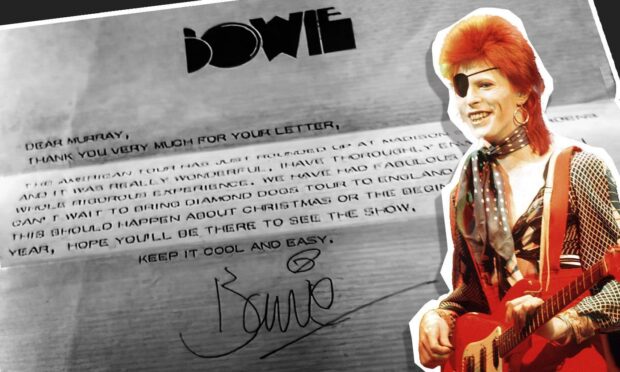

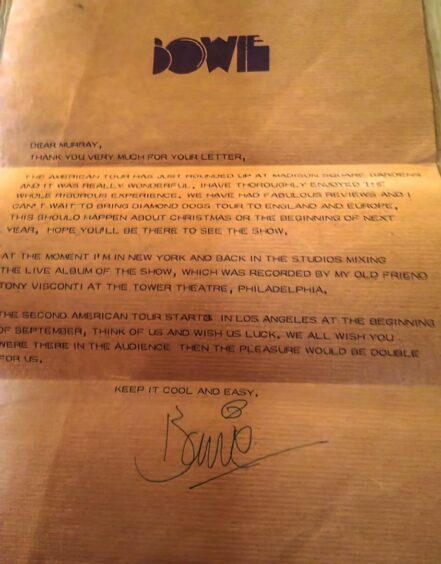

At school someone had his London address and I sent him a letter which I remember as being an outpouring of love and adolescent angst.

Imagine my absolute thrill when Bowie eventually replied – on chic brown paper and with a green signature!

I still have that letter today.

I grew up, got a job in the music industry and I even met Bowie once, backstage at the Brit awards in 1996.

He was performing his song Hallo Spaceboy with Pet Shop Boys, who had remixed it.

When Neil Tennant realised I had never met my hero he told me to follow him and took me to Bowie’s dressing room.

Bowie was exactly as I wanted him to be.

So much so that my first words were “I love your shoes”.

He was wearing rather fabulous stilettos of course.

And what else do you say to the person who gave you a new life 24 years earlier?

The legacy of David Bowie lives on

Bowie remains an icon because he did it first and he did it best.

Yet despite its brilliance I can’t listen to Blackstar, his intensely powerful swansong, without my brain plunging into thoughts of death – Bowie’s, my mother’s, my dad’s and, of course, my own.

For many, Bowie’s death became totemic, as if the universal spark of creativity itself had been blown out by a gust of cruel wind.

I wonder what it was like to choreograph your death as an art statement in this way, leaving so many clues that we had no time to unravel before processing a grief that seemed unreal (most of us had never met him) and yet debilitating?

I know grown men who cried for days after Bowie died.

This wasn’t just the world losing an icon.

This was an admission that our youth, at whatever vintage, was over and that if Bowie could die then we all will.

There will never be an artist like David Bowie – not in my lifetime, not in my godson’s lifetime and not even in a time when humans finally inhabit Mars.

Now, six years after his death and nearing what would have been his 75th birthday on January 8, Bowie’s legacy stands as a reminder of the days when anything seemed possible.