Does saving the world really require major personal sacrifices?

There’s a strand of environmentalism which believes it does, and that we should talk more about that.

Hair shirt environmentalism may not be persuasive, they argue, but it’s necessary.

There’s no doubt we’re in a crisis.

And we will need to make radical changes to find a fair way out of it.

But “living well with less” is especially off-putting to people who already live and work in precarious situations.

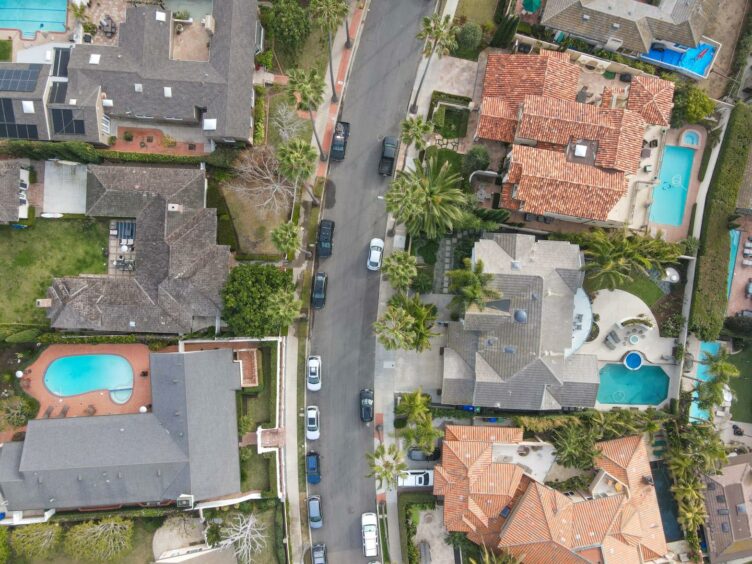

The rich consume far more, of course.

I remember flying over an affluent part of the New Jersey suburbs years ago, seeing row after row of properties, each with their own empty backyard swimming pool.

We must also continue to resist the decades-long efforts by businesses and regulators to persuade us that their failures are our fault.

The radical changes required cannot be delivered by a few more people going vegan, or by the committed taking long-haul trains rather than flights.

But what changes could we make to our way of life that would make it happier while also less carbon-intensive and more resource-efficient?

One idea is the pursuit of “public luxury”, especially in cities and larger towns.

It’s something George Monbiot has talked about a lot.

And it’s one way we can live more enjoyable – even more decadent – lives that are more affordable too, both financially and environmentally.

The case for shared space in public places

Right now our public facilities are typically threadbare, underfunded, and anything but luxurious.

I’ve written a piece in support of public libraries in today’s Scotland on Sunday. pic.twitter.com/S6yBUe0n2k

— Ian Rankin (@Beathhigh) September 5, 2021

I get very distressed when I hear libraries are under threat. But I think I’ve been to my local library once in the last decade.

It hasn’t always been so.

This country used to build more glorious public spaces, especially in the late Victorian period of municipal Fabian idealism.

For a totemic Scottish example, think of the People’s Palace in Glasgow, now in a

miserable state of disrepair.

But imagine every city dotted with reimagined libraries.

Imagine if they included free-to-access stylish co-working spaces, fast free wifi, screens for those who need them, alongside access to books and media.

These “people’s palaces” could be leisure spaces, as well as places for freelancers to work outside the home.

Throw in some fancier sport and fitness spaces with open (bookable) access and free pool tables, perhaps steam baths too.

Include cafes where you don’t get frowned at for bringing your own packed lunch, and the possibilities of true public luxury start to become clear.

We can make them places where people would actively want to spend time, paid for through progressive taxation.

What if we make the car a public luxury?

Or think about personal transportation.

The most urgent steps may be making our towns and cities accessible for walking and wheeling, with better public transport and town planning that doesn’t build in vast commutes.

But there will always be legitimate needs that can only really be met by a car or similar, and not just for disabled people.

Replacing every petrol car with an electric is not the answer.

But what if cars could be provided as a public luxury?

Each local authority could provide a car club, predominantly electrics, with a couple of hours free each week for every local resident.

Car clubs already work well for people committed enough to sign up, but the numbers remain small.

For everyone else, sorting out tax, MOT, insurance, and repairs is an expensive pain – especially since each car is then used about 4% of the time.

It might feel like a treat to pick the right communally-owned vehicle for the occasion (a big van? a sleek estate? a wee runabout?), all well-looked after, and with all the paperwork taken care of for you.

A national system of this sort might be the best possible carrot to help people make the shift.

What if we raised standards for everyone?

For these ideas to work, we need to discard the Thatcherite myth that socialism means worse lives for the people.

The same ideology tells us that public assets must be tatty fallbacks for people who haven’t come out on top, as per the probably apocryphal quote calling anyone on a bus over the age of 30 a failure.

I’m reminded of a scene in the wonderful 1988 Channel 4 drama A Very British Coup, which imagines the victory of a leftwing Labour leader, Harry Perkins.

He’s on the train from Sheffield the day after, and a journalist asks him if he wants to abolish first class travel.

With a twinkle in his eye, he says “no, I’ll abolish second class: I think everyone’s first

class, don’t you?”