I will go a long way to avoid a Burns Supper.

It’s not that I dislike Robert Burns – I revere the man and read him often, and whiles, I used to sing him too.

It’s not that I dislike haggis – I love a good haggis and cheerfully eat it in any month of the year.

And it’s not that I dislike Tam o’ Shanter.

One of five books of Burns I possess is a limited edition of Tam o’ Shanter with illustrations by Balmerino-based artist Derek Robertson.

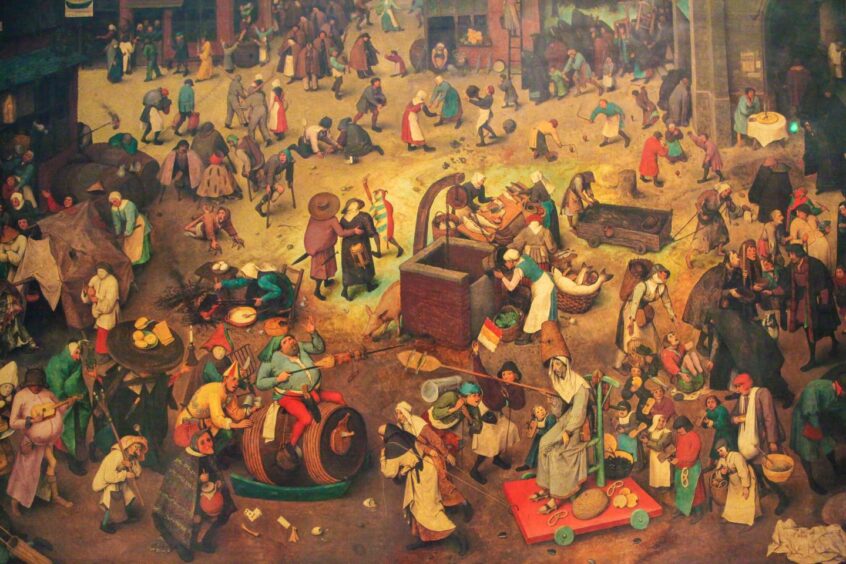

It contains an introduction by David Daiches which includes this sentiment: “The colour and energy of the account is Bruegelesque in its relish of humanity caught in the act.”

It’s not every day that the word “Bruegelesque” appears in The Courier. But if you have ever seen the teeming peasant life in the paintings of the 16th century Dutch-Flemish artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder, you will acknowledge that the description is word-perfect.

So if it’s not Burns himself and it’s not haggis and it’s not Tam o’ Shanter, what’s wrong with Burns Suppers?

It’s the wearisome ritual, it’s the wretched self-importance of Burns Supper bores, the tartanising, and it’s the fact that they condemn our appreciation of our national bard to one day a year.

From the House of Commons to News at Ten, the worst fake Scots accents you will ever hear stir a couple of patronising lines of Burns into a quite meaningless context every January 25.

I suspect the sub-text is “there, that’ll keep the Jocks quiet for another year”.

Robert Burns deserves year-round reading

The newest of my Burns books is last year’s Burns for Every Day of the Year by Pauline Mackay, a lecturer in Burns Studies at Glasgow University.

It is a sublime idea: 366 pieces of Burns (yes, there’s one for February 29, just in case), each with a brief introduction.

I had long pursued the notion of how different a national celebration of Robert Burns would be in the middle of summer instead of – or as well as – the middle of winter.

So instead of January 25 (To A Haggis, alas, surely one of his worst poems and the book’s one unimaginative note), I turned to July, the month Burns died.

The piece for July 25 is Burn’s own epitaph, and which I had never read. I loved this verse:

“Is there a man whose judgement clear,

Can others teach the course to steer,

Yet runs, himself, life’s mad career.

Wild as the wave,

Here pause – and thro’ the starting tear

Survey the grave.”

Burns on the beach anyone?

And then there was the brainwave: why not a midsummer wake on an Ayrshire beach!

And every July 21, the anniversary of his death, it could travel round the country like the Open golf championship.

Barbecued Burns. Haggis burgers.

No rituals, no turgid immortal memories, and when did you last sing all five verse of Auld Lang Syne watching the sunset?

Robert Burns broke so many moulds.

Green Grow the Rashes O is still the only world famous song to suggest that God is female.

And in his poem To A Mouse, his apparently casual use of the phrase “nature’s social union” triggered a thought process in me a few years ago that I have been bringing to bear in my nature writing ever since.

In turn, that led to a discovery that has become central to my work.

Robert Burns, a man of nature

Last year, I published a book called Lakeland Wild, about nature’s place in the English Lake District, where the name and influence of William Wordsworth is an omnipresence.

I have long admired Robert Burns’s nature poems and consider them to be the first utterances of what we now call nature conservation.

I was pleasantly surprised to discover that so did Wordsworth, who name-checked him in his Lyrical Ballads.

Wordsworth’s own nature poetry was the foundation stone of the transcendentalist movement that saw nature rather than God as the Earth’s great creative force.

That in turn attracted the admiration of the American writer Ralph Waldo Emerson.

I started to follow the trail of what happened next.

Emerson’s writing excited the young Thoreau. Thoreau in turn energised Walt Whitman.

And both of these writers caught the imagination of a young Scottish immigrant to Wisconsin called John Muir.

At the height of his fame, Muir met and enthused a young forestry student called Aldo Leopold.

Leopold would go on to write what I still consider to be the greatest single piece of nature writing, A Sand County Almanac, in 1949.

To this day, that inheritance that began with Burns and crossed the Atlantic and came home again, continues to blaze new trails.

And that more or less explains why Burns is often in my head 366 days a year, and why I go a long way to avoid a Burns Supper.