The Nobel Prize for Literature is awarded (I thought I should remind you lest recent events have deluded you into thinking otherwise) to a writer in the field of literature who has produced “the most outstanding work in an ideal direction”.

Who says? Alfred Nobel, that’s who, in his will in 1895. He also specified another criterion, that the writer should “bestow the greatest benefit on mankind”.

What did he mean by “an ideal direction”? The answer, my friend, you might say, is blowing in the wind and has been more or less ever since the first award in 1901.

However, the permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy at the time, Carl David af Wirsen, thought he meant “a lofty and sound idealism” and he would have had the benefit of knowing Nobel and, uniquely, of implementing his will.

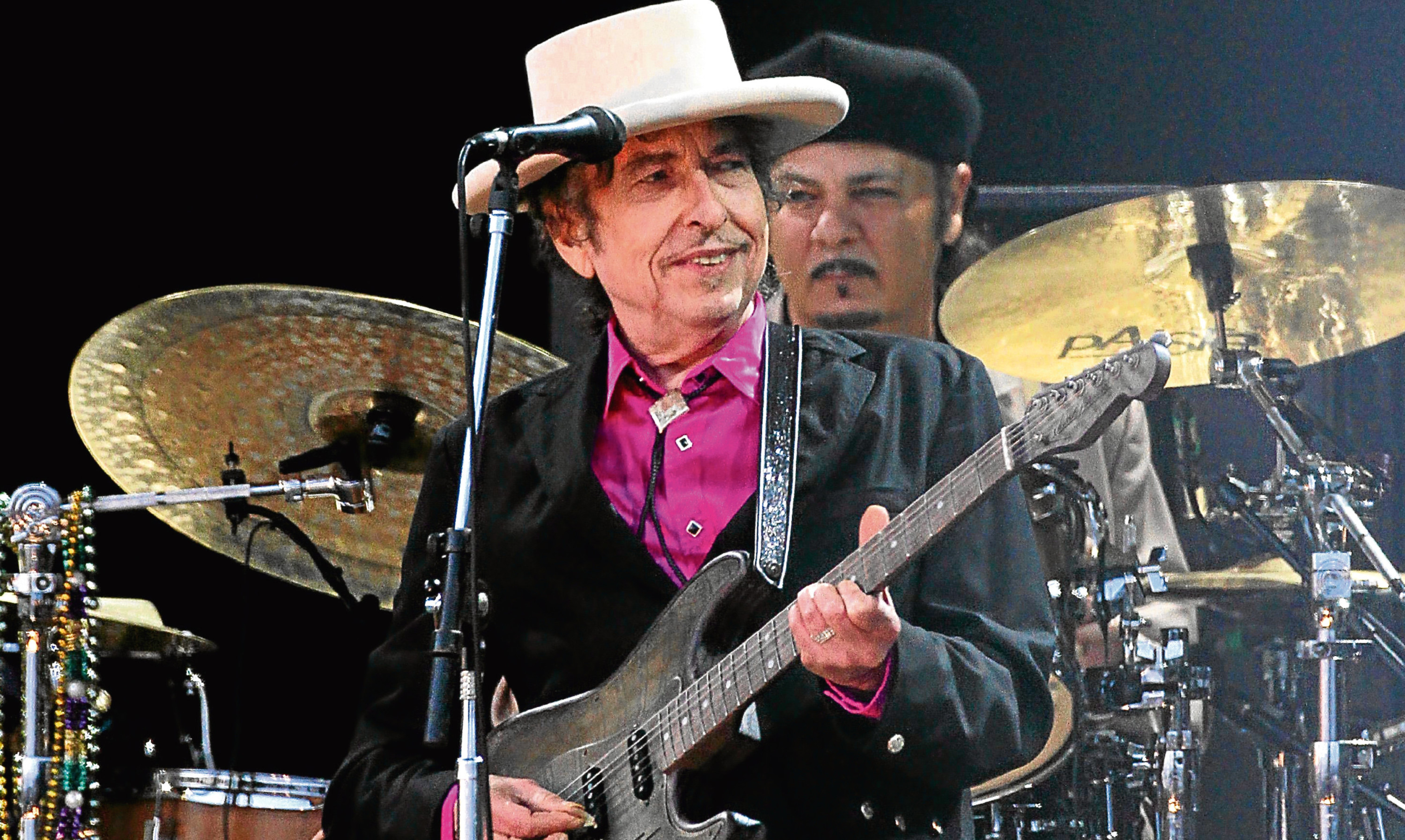

So, Bob Dylan, eh?

Creator of “new poetic expression within the great American song tradition” as the Nobel judges put it?

An ideal direction?

Great benefit to mankind?

Lofty?

At the award announcement, Sara Danius, the permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy (which dispenses the awards) made a speech that seemed to anticipate the possibility of disapproval, as if she was getting her retaliation in first.

Dylan, she said, is “a great poet in the English-speaking tradition… Homer and Sappho wrote poetic texts which were meant to be performed and it’s the same way for Bob Dylan”.

My mind wandered a little bit while I was writing that last sentence and I almost wrote at the end: “And it’s the same way for William McGonagall.”

But it’s true, he wasn’t writing poetry as such, he was writing his own scripts to be performed by him in his touring one-man shows. So was – so is – Bob Dylan.

So am I saying that McGonagall should have got a Nobel Prize? No, I’m not, because his writing didn’t come within a thousand light years of literature.

But given that I have bracketed him and Dylan together, am I saying that the singer doesn’t come within a thousand light years of literature either? Well, yes.

He is an immense presence in American music, in world music for that matter. His earliest albums are pure spring water.

But when he strapped on a Strat and hired himself a band of rock musicians, he became the lead singer of just another rock band with a great future behind him.

For me, he pulled off something remarkable in his 2006 album Modern Times but hopes that he might be on the verge of some kind of second spring were dashed by his painfully woeful Christmas album and his desperately ill-advised album of Sinatra songs. These confirmed that the spring of pure water was dry.

There is a world of difference between poetry and song lyrics. You can read the sharpest, snazziest, jazziest lyrics of, say, Cole Porter and on paper you can admire the craft and wit but at that stage they are only half alive, for they were never meant to be read on the page – they were meant to be sung.

Hear them lifted off the paper and reinvented by, say, a Frank Sinatra or an Ella Fitzgerald and they are something other. Written down, they are raw material, the block of stone from which the sculptor liberates the sculpture within.

Lifted off the page by a truly great interpreter of the American song tradition, they become fully formed works of art. But they were never poetry, never literature – they are music. And that is as true of the lyrics of Bob Dylan as it is of any other songwriter.

Of course, poems are sometimes set to music, which is a different thing for that is a union of two fully formed artistic endeavours, such as when composer Sir Peter Maxwell Davis set the poetry of George Mackay Brown to music.

Now there is a writer who, one might say, the academy has overlooked, one who met Nobel’s criteria with sublime distinction. In my own mind, George Mackay Brown’s work is poetry defined, literature defined. He is my favourite writer, the one I read more than any other.

But I would never read Dylan, although I have occasionally consulted lyric sheets to make out the words. They are especially handy for Modern Times for some of the lyrics tumble over each other like a river full of rapids.

If the Swedish Academy had handed him a Nobel Prize for Music, I would have nodded my approval for his originality, his creativity, his body of work and of the way many of his finest songs can be endlessly reinterpreted by others and emerge unscathed.

But they didn’t do that, they placed him in the category of literature, where he has no place and where the George Mackay Browns of this world will feel justifiably aggrieved from beyond the grave and questioning why the academy itself has chosen a less than ideal direction.