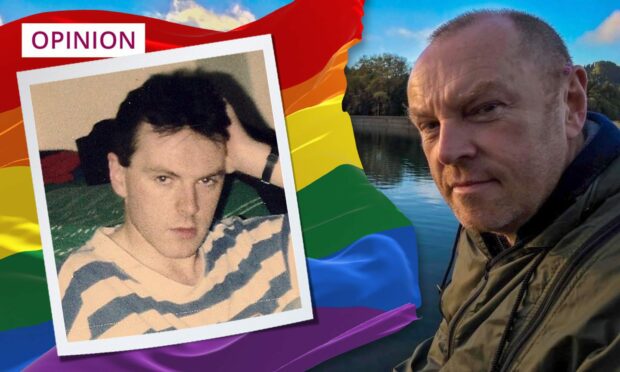

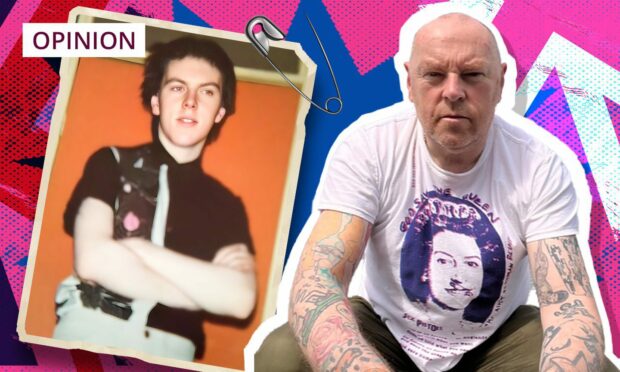

I was a child of the ‘50s, who got through a traumatic childhood by pretending much of it wasn’t really happening.

It would take 12 long years for my life to truly begin.

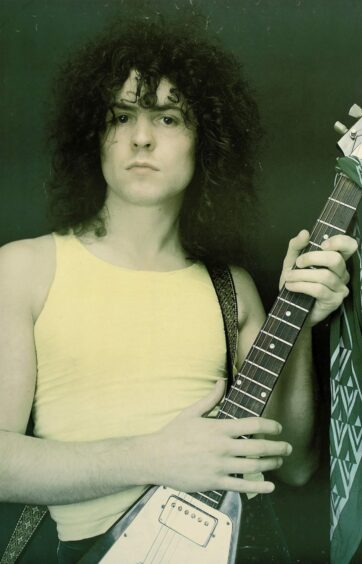

But the song that heralded my re-entry to the world was called Cosmic Dancer.

I thought of it as a direct message from Marc Bolan to me.

Music and art saved me then, just as they do today.

And it all started back in 1971, when my cousin Paul decided it was time I stopped listening to Cilla Black and discovered rock music.

I was approaching adolescence the way an alcoholic approaches a free bar, looking for a safe and quick passage through the hell of other people.

People at school named me “fairy face” as hair started to appear in places other than my head.

I was deemed posh because I came from Dunkeld.

We had moved from a massive flat where I had my own playroom yet were now so poor I had to read hand-me-down girls’ comics donated by our neighbours.

After I’d read Bunty and Judy we hung them in the communal outside toilet, which was out of bounds after dark because weird Jock lived in the attic above.

It was a bewildering time of social change and something had to give.

And that thing was conformity.

‘When you’re a freak there’s no return bus home’

When I learned to drop out is really when I dropped in.

Discovering how to dance at 12 changed everything.

I learned you can always dance to a different tune or choose not to dance at all.

I was the sulky one in the corner, until the day I looked around and noticed other freaks sulking in different corners.

These became my friends.

It was rare we embraced the mainstream, except to dance to disco and to see Grease eight times in 1978.

But even then, raunchy Rizzo was our heroine, not sugar-coated Sandy.

And real freaks danced to Le Freak anyway.

It’s not that I wanted to be a weirdo but nature had plans that nurture just couldn’t support.

The day I got a Bowie feather cut, a library card and a lock on my bedroom door is the day my horizons expanded.

And when you’re a freak there’s no return bus home.

I found my tribe with the waifs and strays

In 1971, through discovering three chords, a drum beat and glitter eye shadow I knew that time could be on the side of the outcast.

When rock music linked the brain to the groin, my next few decades seemed sorted.

The first album my cousin gave me was Electric Warrior by T Rex, which I loved, even just for the cover.

The second offering was In Search Of The Lost Chord by the Moody Blues.

Wherever that errant chord was, I never bothered looking.

What I did find was my tribe, a gang of waifs and strays on the margins of society.

These were the people who thrilled me – mavericks who made their life their work and who didn’t fret about things like paying the rent.

The filth and the freedom

At the start of the ‘80s I lived with many such people in a squat in London and they were some of the happiest days of my life.

Nine of us shared a huge house in Clapham, a Grade 2 listed building which became our playground.

It’s now worth millions yet we lived there rent-free in something akin to an artistic commune.

Someone called Wilf hotwired the electricity and my room was apparently vacated by Marilyn, the androgynous singer.

Dogs roamed the basement and when we all wanted to eat we’d take the door off its hinges and eat off that.

It was so filthy my sister wouldn’t even have a cup of tea when she visited.

But all my adult life I’ve been drawn to the visceral, the feral and the free.

Maybe that’s why I was initially attracted to the Scottish dancer and choreographer Michael Clark, who redefined dance in the ‘80s and whose exhibition Cosmic Dancer opens at Dundee’s V&A on Saturday.

Michael Clark remains a maverick

Back then Michael would be out in wild clubs like the Bell and Taboo, places where you’d get barred for being boring.

We had no money but there was music, Pils, pills and dance.

We’d steal drinks from the bar when people hit the dancefloor.

Michael Clark was a revelation, assimilating classical dance, fashion and music through a punk aesthetic. He ruled.

At the peak of Thatcher’s authoritarianism he made defiantly political, social and sexual statements while dancing like a beautiful fallen angel.

Baryshnikov said he had an aura of Nijinsky.

Which is why I’m massively excited about this exhibition opening and I hope you are too.

Michael Clark remains a totemic figure for us misfits and mavericks, and to revisit his work at this time of sexual fluidity mixed with discord shows it’s not just his dancing that was cosmic.

This is a celebration of doing things your own way and of staying true to your course.

And as such it’s a complete joy.