We were gathered in the school hall for the final assembly of the academic year.

Pupils and staff all there to say goodbye to our school leavers, those soon to enter the world of further study and the workplace.

“This is the last time that you will be judged on your academic results,” said my headteacher in his final address to them.

“As you enter the adult world, you will begin to be judged on the quality of your character, rather than your grades. You will be judged on how you treat and behave towards others.

“Whether your SQA results turn out as you have hoped or not, always remember that they do not define you.”

Admirable sentiments, but of course the reality of this time of year for students, and their teachers, is a little different.

Results arrive tomorrow and the rising tension has been impossible to ignore.

The summer of 2019 was the last time that SQA exam results were awarded in the traditional sense, grades being distributed to the country’s youngsters either via post or, more commonly, text message.

And while the nerves among students have become palpable as we got closer to this week, make no mistake that teachers up and down the country have been losing sleep over them as well.

We work hard on lessons all year long.

Nobody knows what students are capable of better than their teachers.

And yet, when it comes to final results, there is always that looming shadow of the unknown that threatens to derail our hopes.

In my 10 years working as an English teacher, I have experienced both highs and lows when the grades come out.

The pandemic gave us fairer assessment

The absolute elation and pride when results fall in line with, or exceed, expectations.

And the bitter sense of injustice when your pupils are given less than you feel they deserve.

The past two years, of course, have provided an entirely different experience for all involved.

The coronavirus pandemic dictated that SQA results were based on teacher estimates, based on verified coursework and evidence.

Reflecting on 16y/o’s Higher exams being over for the year. What an inhumane and ineffective system we’ve set up to test children. It’s not a test of learning or potential, but rather memory and the limits of mental health. I hope @ScotGovEdu make big changes at SQA @sqanews.

— Steven Shorrock (@StevenShorrock) May 20, 2022

Instead of subjecting students to a one-off final exam, their scores could be judged from a range of work, completed in varying circumstances.

Their futures could be shaped over the course of the academic year, rather than by a single performance in one sitting in May.

What an entirely kinder, fairer form of assessment that was.

The SQA is outdated

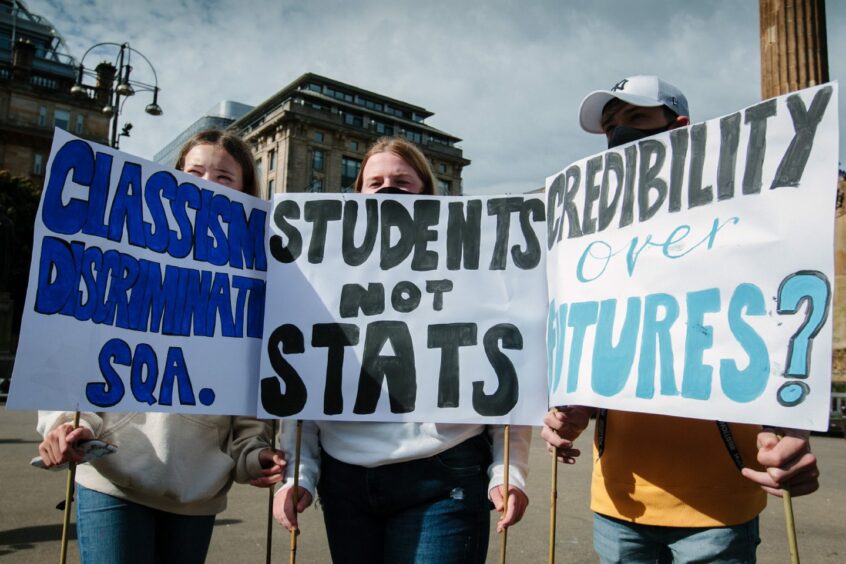

In summer 2020 there was the SQA exams scandal.

Around 124,000 teacher estimates were downgraded – largely in the most deprived areas of the country.

The desires to apply algorithms, to observe the bell curve of results, to maintain historical trends were grossly misjudged.

This led to young people protesting in the streets, and eventually a spectacular mea culpa from John Swinney.

Small wonder there are plans to overhaul our outdated system, and replace the SQA with a new governing body.

But an entire change of philosophy is required here.

If this is simply a rebranding exercise, with the same management and staff, working from the same premises, with the same objectives and mindsets, then there will be no discernible benefit for our country’s students.

We need more than a shiny new logo to print on the exam papers.

Teachers know their pupils best

So, what practical improvements can be recommended?

Let’s take my subject, English, to begin with.

It’s SQA results tomorrow. This is my story. Due to bullying, partly, I failed all my exams in 5th year, except for a C in Higher English. Then I worked on a building site before doing resits. I managed three B’s and that got me into Paisley Tech. Where I am now a Professor. 1/2

— colin clark (@profcolinclark) August 3, 2020

Currently, in National Qualifications, pupils have 45 minutes to write an essay about a text they have studied – without access to the text itself.

This is madness.

In preparation, students spend so much time memorising quotations to use in their essay. I know that this is a huge cause of anxiety for candidates.

Why are we interested in assessing their ability to commit chunks of literature to memory?

Surely, the real skills we ought to be evaluating revolve around analysis, reasoning, logic and discussion.

Would a book reviewer for a magazine be required to submit their copy without having access to the novel, and only 45 minutes to write it? Of course not.

Give students a copy of whatever text it is they’re writing an essay about, and at least twice as long.

I’m sure teachers of other subjects could chime in with their own specific improvements, but it seems clear to me that stronger weighting should be given to coursework completed throughout the year.

Teacher estimates and judgement ought to be taken more firmly into consideration, as they were in 2020 and 2021. Nobody knows the students better.

As my headteacher said: beyond school, your exam results do not define you.

The world judges us on how we treat others, and how we make them feel.

These messages are something the new exam board, in whatever form is materialises, would do well to learn from.

Alan Gillespie grew up in Glenrothes and teaches at an independent school in Glasgow. His debut novel ‘The Mash House’ was published in 2021.

Conversation