The collective genius of Perth and Kinross Council, the National Trust for Scotland and the Forestry Commission is stroking its collective chin.

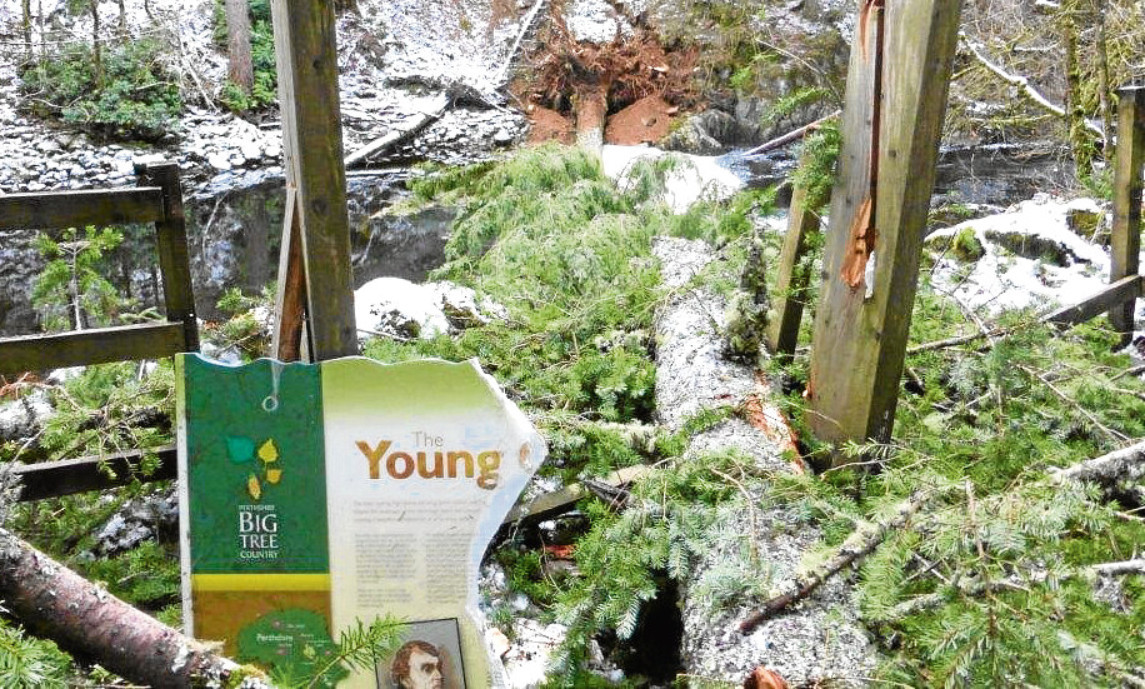

It wonders what to do with a 211ft-high Douglas fir which is now, alas, a 211ft-long horizontal Douglas fir.

So I should like to offer the following dollop of compost to aid their deliberations.

There is, of course, a very compelling argument for allowing the tree to rest in peace.

In time (a great deal of time given the size of the thing), it will break down, the way all fallen trees do and by leaching its massive reservoir of nutrients back into the soil, effectively become compost itself. Many young trees will flourish where it fell.

In the process, it will feed and sustain millions of invertebrates and the creatures that prey on those millions.

The American poet Robert Frost called the process “the slow, smokeless burning of decay”.

So that’s an option, the one of which nature would approve.

The trouble with that option is, well…people.

The Hermitage is not just woodland, it has become tourism.

All three organisations mentioned above and VisitScotland of course and TripAdvisor and a dozen other walk-this-way service-providers, promote the Hermitage relentlessly.

Sometimes, in high summer it can feel as if there are more people than trees.

It is, of course, much loved and much cherished by the natives, as it should be, because as man-made intrusions on the landscape go, it is something of a wonder.

But tourism likes its woodlands to be tidy places and equates the sight of a fallen tree with neglect.

No matter that nature disagrees profoundly with the assessment, tourism is – arguably at least – the priority for those bureaucracies that have a finger in the Hermitage pie.

So here is option two…

Use the timber to create a woodland shrine to the memory of David Douglas, son of a Scone stonemason, pupil of Kinnoull School and the product of a seven-year apprenticeship at Scone Palace who became a global superstar of 19th Century plant collecting expeditions.

Without Douglas, what Perth and Kinross Council loves to trumpet as Big Tree Country simply would not exist.

The “planting dukes” would have had very little seed to stuff into the barrels of the cannons with which they reputedly afforested the more inaccessible airts of their fiefdom.

Douglas was dispatched by the Royal Horticultural Society in London to the Pacific Northwest.

His remarkable energies and talents gave us (among more than 200 species he introduced to Britain) the Douglas fir, Sitka spruce (a wondrous wild tree in south-east Alaska but which the Forestry Commission has misused, often grotesquely), lodgepole pine, grand fir and noble pine, not to mention flowering currants, lupins and Californian poppies.

There is already a monument to Douglas in the churchyard in Scone but it is as grim a pile of overblown Victorian excess as you are ever likely to clap eyes on.

There is also the pavilion at Pitlochry Festival Theatre, with an essentially educational purpose.

What there is not is a quiet woodland shrine to one of the world’s great woodlanders in an appropriate setting.

So if nature’s solution – leave the tree where it lies – is not acceptable to the furrowed brows of bureaucracy and the tourist industry, what could be more appropriate than to clear a space around the tree and, where it lies, build a shrine to the man who gave its name?

As to the notion advanced by the National Trust for Scotland that the tree “will be a great loss to Perthshire”, no, I don’t think it will, at least not for long and nothing like the great loss to Perthshire occasioned by the wilful destruction of a Scots pine in the grounds of Perth Academy in 2013.

At the Hermitage, all that has happened is that one tree among millions has given up the ghost.

If the tree is left alone where it lies, or if it is recycled into something beautifully man-made, there is no loss.

And there are around 20 Douglas firs across Scotland more than 200ft and many, many young ones to take their place in time.

A saner assessment of our relationship with trees was provided by Ralph Waldo Emerson, the American writer and a contemporary of David Douglas:

“In the woods, too, a man casts off his years, as the snake his slough and at what period soever of life is always a child. In the woods is perpetual youth.

“Within these plantations of God, a decorum and sanctity reign, a perennial festival is dressed and the guest sees not how he should tire of them in a thousand years. In the woods, we return to reason and faith.”

It does rather make me wonder what the Douglas-Emerson generation knew about trees that we don’t know now.