A few good pals of mine have been getting targeted online by barrages of seemingly dodgy accounts.

These accounts all feel a bit ‘fake’. Very one-note and angry.

Lots of these toxic accounts, across Twitter and Facebook in particular, seem to focus their energies tearing into Scottish issues like the upcoming referendum, the Scots language, and SNP and Tory parties.

And since many of us rely on social media for our news and much of our social interaction, it’s worth the occasional health check, to see how far we can trust what we’re seeing.

I have good news and bad news.

The good news is that the big state actors, your Russias, your UK governments, seem less able to wield social feeds like weapons of war than you might have feared.

The bad news is that influential organisations are still operating massive armies of weaponised accounts online.

And that they are harder to spot than ever.

I got on this scent after Billy Kay, Iona Fyfe and Len Pennie all got dog’s abuse online for speaking in Scots.

Billy’s in particular was an interesting case.

He gave a “time for reflection” at Holyrood.

These are brief addresses that our MSPs hear at the start of the work day on Wednesdays.

But he did it in and on Scots, and was set upon rabidly.

A democratic discussion became a social division

It reminded me of 2016, when the Brexit referendum was very heavily influenced by bot activity online, particularly on Facebook and Twitter.

According to a piece published in the Royal Economic Society, social bots were fired up around live events, and would try to amplify extreme voices.

This amplification of the fringe characters the Brexit debate and drove the two sides further apart.

It caused a democratic discussion to become a social division.

And the scars of that live on yet.

Folk got too overly trenchant in their Brexit views, and now cannot hear different.

So the two-party system in England is forced to sink along with this self-sabotage Brexit, regardless of what government gets in.

What is a bot?

By generally accepted definitions, a social bot is an at least partially automated account online.

These are accounts controlled by software rather than directly by a human.

And there’s absolutely tonnes of them.

Maybe up to 20% of all accounts on social media are at least partly software-operated.

And when they act in concert, they can completely obscure the reality of live events.

Researchers have estimated that 70% of tweets around stock market spikes in 2019 were bots.

So when journalists, politicians, or the likes of me and you hear about some crisis event, and nip online to see what’s going on, there’s an extremely high chance that our initial impressions of the breaking news are being curated by bots.

We conflate popularity with legitimacy

So, is it these bot armies that were for some reason taking on Billy, and my other Scots language amigos?

It seems not. There’s other dirty work at play here.

In the social media age, we’re prone to conflating popularity with legitimacy.

If you say something online and it gains enough traction, there’s a good chance a lot of people will take you seriously.

Italian politicians were found to be weaponising this effect in elections.

They were buying thousands of fake followers and boosting all of their statements online by paying for likes and shares and engagements.

This gave the reporters and commentators covering the election the impression that these politicians were getting great support from the population.

Think about what happens here.

You see a post that says “I cannae stand Nicola Sturgeon. She a right wee nippy sweetie”. It has no interaction and is from an anonymous account with few followers. So, you subconsciously log it as a loser opinion.

If the same Facebook post, or tweet has a hundred and fifty likes, cry reacts or hearts on Facebook, or a hundred retweets on Twitter you think “ken what, that’s a popular thought. People in my wider social sphere think it’s true enough.”

That thought is in your head.

How easy is this to do?

And so, my dear readers, I did a quick experiment.

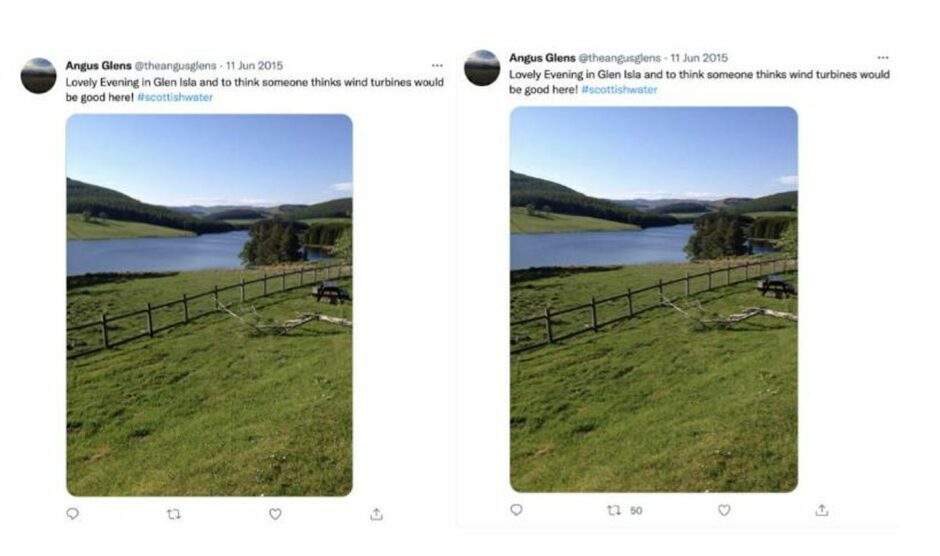

I had a wee trawl through our local social media feeds, and found an unloved post from a derelict twitter account from seven years ago.

I then went to a website called Social Wick and bought 50 retweets for the tweet.

It cost me 72 pence. If I was being more sophisticated, I would’ve bought maybe 73 retweets and 850 likes, so it looks more organic and natural.

But it was that simple. And people who wish to seem like they are thought leaders can effortlessly boost their own numbers like this.

Perhaps that is what was happening to Billy and others.

A handful of real people who have become radicalised to some niche political or social ideology can each run perhaps a dozen accounts each.

They can all interact together, they can orchestrate attacks, and they can share one-another’s’ opinions.

Add to that some cheaply-bought shares, followers and interactions and suddenly you can create the facade of a popular opinion.

Take online information with two pinches of salt

These little nodes of extreme opinion now exist all across the internet.

It’s intriguing how many trolls have been attacking me online today, who have fake identities and have no followers at all, or fewer than 10. Someone is up to something!

— Chris Bryant (@RhonddaBryant) February 8, 2022

They are not state controlled, nor are they truly fully automated.

But by being canny and clever with how they carry on online, they can easily deceive us into thinking that their fringe opinions represent a meaningful chunk of our society.

This simulacrum of reality from social media is most dangerous to opinion formers, reporters and journalists, who pick up these fringe opinions and legitimise them by reproducing them in papers of record, in radio and television broadcasts.

For the likes of us, all we can do is be careful and be savvy.

Anything you see online, take with two pinches of salt.

Try not to tumble into any extreme little online groups.

And if these little hate groups ever come for you, remember; they are a Potemkin lynch mob, not a real thing.

Conversation