People of Perth may not regard their city as a hotbed of radicalism – I can’t say I did when growing up there – but it has a strong claim to have been at the forefront of Scotland’s long and circuitous march to self-government.

At the Scottish Conservative conference in 1968, Ted Heath, then leader of the opposition, shocked delegates in the City Hall when he committed the Tories to supporting an elected assembly for Scotland, in what became known as the Declaration of Perth.

When Perth went SNP yellow in 1974 and the party was riding high, devolution seemed inevitable.

However, the seat’s reversion to Tory blue at the 1979 general election saw Scotland’s constitutional journey shudder to a halt.

It was just a pause, albeit lengthy.

In the same hall as Mr Heath had spoken, Alex Salmond was first elected SNP leader in 1990.

Five years after that, Roseanna Cunningham won a famous by-election victory in Perth, since then the city has been continuously represented by the SNP at Westminster and Holyrood.

Earlier this month, Perth played a cameo role in the strange spectacle of our next prime minster being chosen by Conservative members (who number only 0.3 per cent of the UK population, and of whom around six per cent live in Scotland).

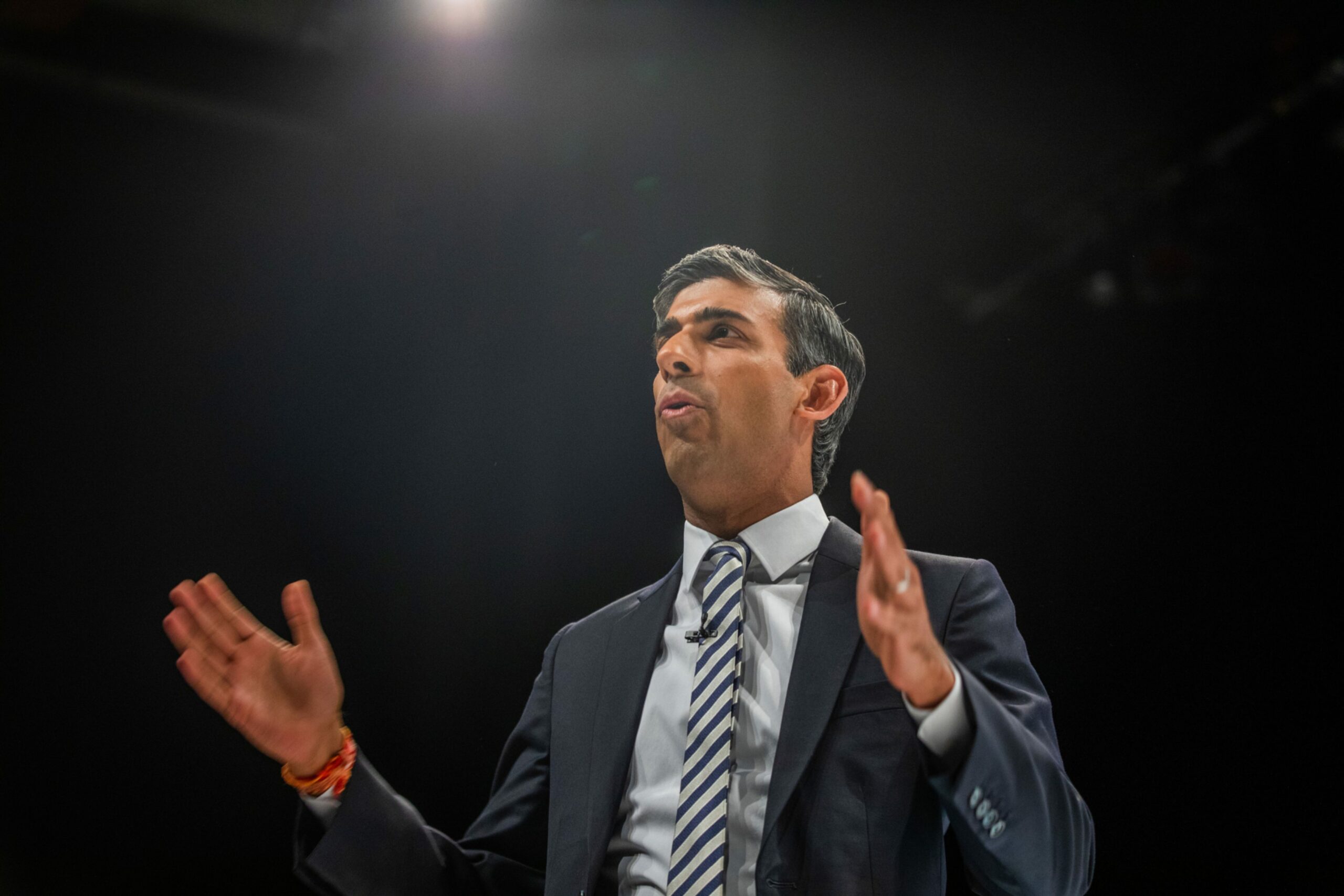

Unfortunately, the sole Scottish hustings between Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak, in Perth Concert Hall, made headlines because of the nastiness of some protesters outside.

The ugly banner emblazoned “Tory Scum Out” was dehumanising defamation, not a reasoned declaration.

Tories want to trespass on to Holyrood’s turf

Yet as well as condemning abuse, we ought to also to pay greater attention to what was said inside the hall.

There were indications of a negative and hardening attitude among Conservatives to the role of the Scottish Parliament as well as decisions of the SNP government, and a desire on the part of both Ms Truss and Mr Sunak to trespass onto Holyrood’s turf.

For example, questioners from the floor wanted to know how a British prime minister could promote fracking and new nuclear power in Scotland, despite the relevant planning powers being devolved.

They may not have intended to convey this to those tuning in, but both candidates gave the impression (to me at least) that the Scottish Parliament would never have been reconvened in their idealised version of the UK.

Had income tax and welfare powers not been transferred to Holyrood in the aftermath of the independence referendum (by a Tory government, let it be remembered), there is not the slightest chance that the Brexit version of the Conservative Party would cede such control now.

All of which demonstrates that, more than half a century since the Declaration of Perth, the Tories have still not reached a settled will about Scottish self-government.

The tentatively supportive stance of Mr Heath in the 1960s was reversed by Margaret Thatcher in the 1970s.

Then, when a Scottish parliament was finally established in 1999, the Conservatives were not only reconciled to it but became enthusiastic participants.

This reached its zenith under Ruth Davidson’s leadership, when Conservative MSPs supplanted Labour to be the principal opposition party at Holyrood, even harbouring dreams of ousting the SNP and forming the administration.

Conservatives are pursuing an agenda of creeping integration

Now, rather than winning office in the Scottish Parliament, the Tory mindset seems more focused on circumventing devolved powers and controlling events in Scotland from Westminster.

Mr Sunak chose an obscure subject at the Perth hustings to pick a fight with the SNP, when he said he wanted to pass a law to ensure the Scottish Government must produce data about public services that are “directly comparable” with statistics south of the border.

He should perhaps be careful what he wishes for, but it provides an insight into an irony about the Tories in the age of Brexit, as do much more substantial measures such as the UK’s new internal market rules.

Having, in my view, mischaracterised the EU as wanting to impose excessive uniformity on its member countries, Conservatives are open to the charge of pursuing an agenda of creeping integration across the nations of the UK.

Such an approach may have their own activists cheering in the aisles, but it would flop among the Scottish electorate at large.

Kevin Pringle is a former special adviser to the First Minister in the Scottish Government from 2007-12. Thereafter he was the SNP’s communications director during the independence referendum campaign and through to the 2015 general election.

Conversation