You remember where you were at the moment of any momentous world event.

At my parents’ wedding reception in April 1960, a man rushed in and shouted “Verwoerd’s been shot”.

That was the architect of apartheid, HF Verwoerd, who would survive that, but not a fatal assassination by a knifeman in 1966.

Fast-forward to a wee girl, glowering, hating on her fish pie. That was me. My mother made a fish pie with pilchards and I absolutely loathed it.

But, there I was, and we were glued to the radio (yes, the radio – South Africa only got television in 1976).

My father’s fork paused in mid-air, he sat completely still as the radio crackled with the now famous words: “One small step for man….”

That, of course was Neil Armstrong walking on the moon on July 20 1969. The moon looked different to my little self after that.

It was quite late at night in the land Down Under when I flicked sleepily through the channels before bed. A tall tower, ablaze, filled the screen.

I thought it was a disaster movie, and switched off. The attack on the Twin Towers on September 11 2001 would resonate through the world for decades. It still does.

On January 18 2003, a Saturday afternoon, I was sitting at the Brumbies Club in Canberra as the sky went black, and fear crackled through us.

Someone came in, wide-eyed and said the petrol station in Duffy had gone. Blown sky high in a suburb to the north of us, by the advancing bushfires.

An apocalyptic event

We walked home quickly with our shirts covering our mouths, while burning leaves filled the air and cockatoos fell from the sky. It was apocalyptic.

And the 2013 bushfires were too: 500 homes were lost, four people died, along with livestock and animals too numerous to count.

It was Boxing Day 2004 when the news of the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami broke in Australia and we watched, in helpless horror, as nature’s might claimed land and lives on an unimaginable scale.

When a similar disaster struck Japan in March 2011, we were about to fly to Scotland.

When Mandela died

I was in at home in Australia when the message came from South Africa in December 2013. Mandela was dead. This could not be happening.

He was our saviour, all hope rested with him. He carried us from the terrible darkness. We couldn’t believe he could be gone. But he was.

I wasn’t alone in crying for days; millions cried with me. I watched that wonderful clip of Madiba appearing on stage in Paris at a Johnny Clegg concert over, and over again.

We had a remembrance service for him in Canberra. The South African expat community sobbed as one. In the condolence book we wrote “hamba kahle Madiba” – go well Madiba.

We couldn’t see through our tears.

When the news began to break on the afternoon of September 8 that the Queen was likely dying, myself and my Courier colleagues were working to a print deadline.

There was collective frisson, a silent gasp of disbelief. The Queen is always here, she always has been. This couldn’t be happening.

But it was.

And now, autumn is creeping in and darkness comes ever earlier, and I think we all need hope.

Something to balance the pending misery of a cruel winter, where people will have to choose between freezing and starving, where more and more businesses are closing because they can’t afford to keep the lights on, where people could be driven on to the frozen streets for lack of a place to stay.

Finding hope in Patagonia

We need hope. I found it this week in Patagonia. The clothing company that is.

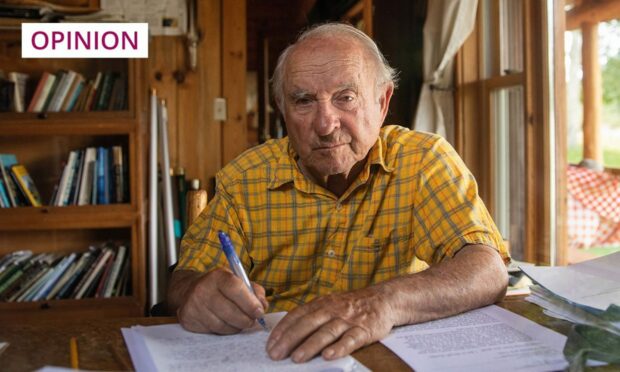

Founder and reluctant billionaire Yvon Chouinard – who turned his passion for rock climbing into one of the world’s most successful sportswear brands – is giving his entire company away to a carefully tailored trust and non-profit.

It’s designed to put all of the company’s profits, some $100 million a year, into saving the planet.

“As of now, Earth is our only shareholder,” the company announced. “ALL profits, in perpetuity, will go to our mission to ‘save our home planet’.”

The 83-year-old Chouinard, along with his wife, two children and clever lawyers, have created a structure whereby all Patagonia proceeds will go to benefit environmental efforts.

All of them.

“Instead of ‘going public’, you could say we’re ‘going purpose’,” said Chouinard.

“Instead of extracting value from nature and transforming it into wealth for investors, we’ll use the wealth Patagonia creates to protect the source of all wealth.”

That feels like a momentous moment. And it gives me hope.

Conversation