Is there anything more exciting than dreaming up a Halloween costume?

As a kid, I would start the process shortly after New Year. It needed the full ten months of planning, obviously. There were mood boards to make, and this was pre-Pinterest, all printouts.

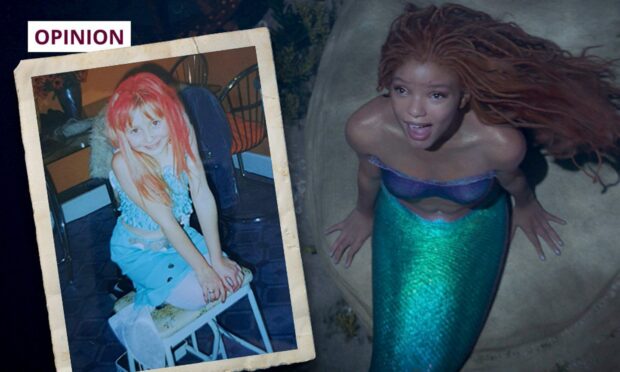

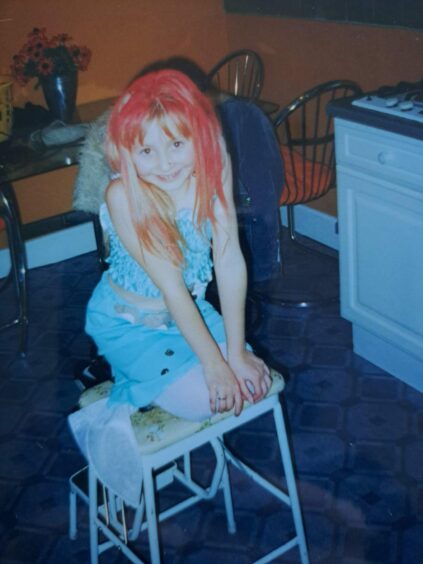

My favourite – and most elaborate – costume was when I was about seven years old. I went as Ariel, from The Little Mermaid.

Curious, brave and determined, she was my favourite Disney princess. Not Sleeping Beauty, or Cinderella, whose blonde locks and long dresses would have made things much more achievable.

No, little Rebecca (a blonde-haired, leg-having child) wanted to be the scarlet-haired fish girl.

My parents, mad as they are, indulged me. Dad fashioned me a tail. Mum spray-dyed my hair with streaks of fire-engine red that washed out overnight (but stuck to her beautiful white bathtub for months).

And when I looked in the mirror, I saw Ariel.

I was Under the Sea and over the moon. I didn’t even care that I didn’t win the costume competition.

Because getting to look like my hero for a night was one of the best experiences of my little life. I felt like I could be anything I wanted; part of any world, as Ariel might put it.

I hadn’t thought about that costume in a long time, but then Mermaidgate happened.

A Black Little Mermaid – cheap marketing ploy, or progressive media move?

In case you’ve missed it – the Internet’s latest war on woke involves the very same Little Mermaid I dressed as for Halloween 20 years ago.

The 1990 animated classic is the latest in a slew of live action reboots nobody asked for, following the likes of Dumbo, The Lion King and The Jungle Book into the tepid world of 21st century CGI.

And this time, Ariel is a Black girl, and her signature red tresses are gorgeous russet braids.

Obviously, the anti-woke brigade are kicking off and – because this Internet is a hellscape – going after the young Black actress playing the part with their racist backlash.

"Well the original little mermai-"

The original The Little Mermaid is a queer man's self-insertion character, longing to be able to be in a relationship with another man, and at the end the mermaid dies.

You don't care about the original, mate.

— Nome (@NomeDaBarbarian) September 12, 2022

Now, I’ll be honest: my own reaction to news of this remake was not a positive one. In fact, I was completely opposed to it.

I was opposed to it because I think it’s a lazy, cheap move from the studio executives who, instead of investing in new writers and original stories, are happy to capitalise on the arrested development of a generation (myself included) for whom nostalgia is the ultimate cultural opiate.

I was opposed because live action remakes of animated films consistently add nothing to the story, and they take away all the visual charm of hand-drawn or painted originals.

But I was not opposed because the mermaid – a made-up creature – has a different colour of skin to the original.

Still, I thought it was irrelevant and mundane, and I dismissed it as such.

But Halloween is coming up, so I’ve started thinking about my costume (a little later than seven-year-old me would have liked).

Everyone deserves to feel like a princess

It would be fairly easy – if ridiculous – for me to dress as almost any Disney princess. Rapunzel and Elsa have been added since I was wee, both with pale skin and long blonde hair, albeit in that weird new animation style.

I’ll always have Alice, Aurora and Cinders in the dress-up arsenal; even the 1990 Ariel, if I want to sacrifice another bathroom to some red hair chalk.

If I want to go live action, I’ve my pick of icons – Elle Woods, Cher from Clueless, Captain Marvel.

There’s no shortage of leading ladies who look like me.

So every Halloween I can feel cool and whimsical, and it’s just like being a kid again for one night.

But Black women my age don’t have that same easily-accessible joy. They never had a Little Mermaid, or a Sleeping Beauty, or a Cinderella that looked like them.

This stuff matters.

Why does everyone need ‘represented’?

Studies show that poor media representation has a significant negative effect on how people from minority and marginalised groups view themselves.

But it’s not just about mitigating harm – or, as keyboard warriors might put it, making sure no “snowflakes” feel excluded.

Representation in film and TV also has the power to affect the real world in a positive way.

Humans trust what they know, and they like what they trust. We in Scotland spend upwards of five hours a day watching TV – we know the characters on screen, and trust them more for it, whether they’re fictional or not.

That makes media representation the second most powerful way to influence societal attitudes towards minority groups, behind knowing someone personally from the group in question.

It has a measurable knock-on effect. Firstly, changing the tone and prevalence of news coverage about those groups, which adds up to reformed laws and behaviours in the real world.

And now, within a film and TV industry that remains disproportionately white, Black kids have a Little Mermaid they can dress up as, and see their hero, melanin and all, in the mirror.

That’s not stupid or irrelevant at all. That’s huge.

So I’m no longer opposed to this remake, money-grabbing and calculated as it may be. Because it’s not about me, or you, or the studios, or the money.

It’s about the kids, all of them – tiny and happy and in freezing mermaid-tails for the next 20 Halloweens.

Conversation