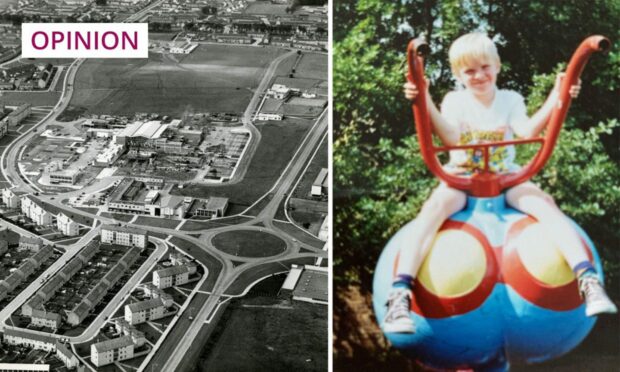

At the end of my mother’s front garden in Glenrothes is the playpark where we spent most of our childhood.

It is unique, this playpark, in that it features absolutely no child-friendly equipment.

I daresay there is not another park like it in the world.

Instead of rubbery tarmac or sensory games, there are grey brick walls, brutalist concrete cubes, some discarded boulders, and three enormous yellow concrete crocodiles.

None of your swings and chutes and roundabout.

To play in the Crocodile Park, your imagination has to do the work for you.

The 2021 BBC documentary Meet You at the Hippos highlighted Glenrothes‘s civic art, nourished by its New Town status and the desire to create cultural identity where there was none.

The documentary presenter, Mark Bonnar, focused on his architect father, Stan, and the concepts behind his work in Glenrothes, East Kilbride, and beyond.

But for myself, as a wee boy, growing up with instant access to a street menagerie of concrete crocodiles/hippos/elephants/tulips/dinosaurs/television sets was brilliant.

Glenrothes public art still delights me – and now my daughter too

There was something weird and otherworldly about the sculptures that fired the juices.

Where else could a five-year-old scale to the top of an enormous elephant and skid down its trunk?

At the time, the thing seemed so big it must be true to scale.

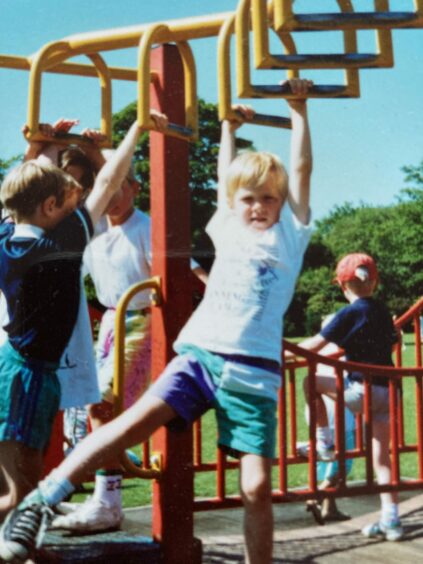

I lost count of the number of times we fell off and cracked out heads.

The games we came up with in these deathtrap parks were tremendous.

My best pal was called Scrag, and together we devised a series of characters called the Super Babies – think Ninja Turtles wearing Pampers – with plots as complex as anything the Marvel franchise could come up with.

The giant irises at the Leslie Roundabout are one of Glenrothes’s signature, postcard images.

A remnant from the Glasgow Garden Festival in 1988, I remember the childhood wonder these landmark flowers held.

As we drove past, my parents would unwind the window and I’d pour water on the sculpture from an imaginary watering can, to help them grow.

It’s a performance, a tradition, which I now enjoy repeating with my own daughter.

Public art is part of what makes Glenrothes so vibrant today

As an adult, it took a while for me to characterise Glenrothes as having been a good place to grow up.

As I moved away, to Stirling and the Highlands and then Glasgow, it was easy to criticise the town to people who’d never been.

I remember joking that it was “the Cumbernauld of the East”.

The 2009 award of the notorious Plook on the Plinth title, for being the most dismal town in Scotland, did not help matters.

The New Towns often seemed to be nominated in this conversation.

But when I return to Glenrothes now, to visit friends and family, it feels far more joyful.

Green, busy, vibrant.

Fife: a kingdom of creativity

Fife has a treasured heritage when it comes to literature, stretching back to the Robinson Crusoe connections at Lower Largo.

More recently of course, there are the immeasurable contributions to the crime genre made by Ian Rankin and Val McDermid.

Not to mention my own literary hero, Iain Banks, who was born at North Queensferry.

Banks’s novels are pitched with a sublime mixture of darkness and humour.

When my own debut novel, The Mash House, was published last year, I felt very aware of the rich line of Fife writers that I am attempting to follow.

What is it about Fife that has inspired so many writers (and not to mention the Kingdom’s artists and musicians)?

Perhaps the bridges over the Tay and the Forth give us a collective sense of curiosity – something about the water, the coasts, the feeling of being at the edge of something.

For me, growing up surrounded by the New Town art certainly fed my creative muscles.

We used to play elaborate team games.

Dozens of neighbourhood kids, each with specific characters to roleplay and parks to defend.

These took place across the whole scheme of Pitcoudie, which was built on a hill, and lasted all afternoon and night.

Hippos, irises and crocodiles – memories of a Glenrothes childhood

When it came to writing my first book – which was set in the West Highlands after a teaching gig there – I leaned heavily on my Fife upbringing.

The stretching rural landscapes, the endless shore, the small cast of village characters in the book all owe much to the Kingdom.

If you know where to look, you’ll see there are characters in the book who are based on my pals from Glenrothes, pubs in the town, patterns of speech.

Writers are often magpies, borrowing material from the people and places they’ve encountered and repurposing it.

When the Glenrothes Development Corporation decided to smatter the town with an assortment of, let’s face it, pretty surreal sculptures in playparks and public spaces, I’m sure they were trying to instil the place with a sense of personality, identity and belonging.

Artists like Stan Bonnar were able to make a lasting legacy on the fabric of the new towns.

What they perhaps did not realise is that they would be nurturing creativity, feeding children’s imaginations, and inspiring future generations of writers and artists as well.

For me and my childhood pals, no matter where we go now, in our memories we will always have the hippos, the irises, and the Crocodile Park.

Alan Gillespie grew up in Glenrothes and teaches at an independent school in Glasgow. His debut novel, The Mash House, was published in 2021.

Conversation