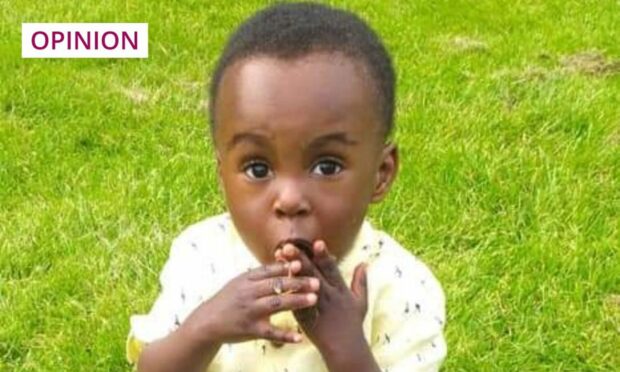

In a world awash with horror, tragedy and poverty some stories stay with you. I’ve found myself going to bed at night and waking again the next day with the death of a two-year-old boy on my mind.

A toddler who, a coroner declared this week, died in 2020 because of prolonged exposure to mould in his own home.

If your first thought was where did this happen, or where did he come from, then I’m sadder still.

Because this happened in Britain.

In public housing.

And despite his parents protestations about the black mould that climbed round the radiators, swamped the bathroom and the windowsills.

That word – home – means so much to all of us.

A sanctuary maybe. Somewhere that should be safe, secure, ours.

Somewhere you can enter, closing the door behind you, and leave much of life’s troubles beyond its bounds.

For this little boy that closed door meant something much more sinister.

Mould led to death of this little boy

His medical reports said he had breathing problems his whole life.

That’s not an excuse, that’s the point.

His parents repeatedly complained about the mould but were told on the rare occasions someone replied to paint over it.

Notes on the mould in his house never made it to his GP. So when the little boy got ill, the cause wasn’t obvious.

Every day of his 700 odd days on this planet, that little boy was breathing in spores because of damp and poor ventilation in a house that was supposed to be home.

Those spores multiply when houses generate condensation, forming water droplets that leave walls and surfaces damp.

Every day with the heating off and the windows tightly closed is boomtown for mould to prosper.

The mistake is to think that this little boy’s loss of life is a tragedy because it was so unique.

To think it’s a simple story of a missed email, an unreturned call, over-worked staff in under-resourced services.

That he just fell through the cracks in a system.

That’s all fair and true until you take a step back and see it’s not a system but a sieve.

Boy’s mould death is a symptom of wider housing failings

This isn’t the story of one particularly unlucky child, it’s a symbol for the thousands of people who we know are living in substandard housing across the whole of the United Kingdom.

And the next time you hear someone casually say this a wake up call for all that needs to change, ask what happened after the Grenfell fire?

That was five years ago and still we have deep and growing levels of destitution across our country.

There are 900 Ukranians living in a boat off Edinburgh’s Leith docks because there’s no room for them in the temporary accommodation system.

That’s because the average time people spend in temporary accommodation now is well over 200 days.

They can’t get houses because we’re not building nearly enough.

Meanwhile the catastrophic and decade-long underfunding of housing generally means repairs go undone and mould and damp prosper.

Kids walk around on bare floor boards. Pennies in the meter create heat that flies straight out the cracks in our poorly insulated homes.

So I’m sad for that little boy. I’m sad for what his life story now represents and I’m sad because I can’t see things getting any better any time soon.

Yes all this takes money at a time when there’s so little of it, but it also takes political will.

This is systemic neglect on an industrial scale.

We’re paying for it with our taxes and we’re complicit in it until we demand that housing gets the attention it deserves.

Conversation