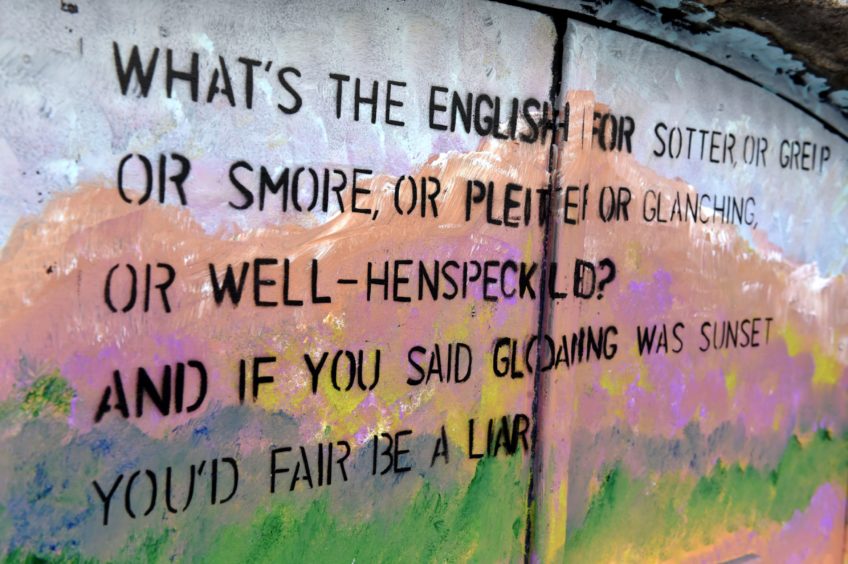

Scots words are braw. They improve any text, as apt use of interesting words of any stripe will.

I have quite a collection of Scots dictionaries (though if anyone wants to donate a Jamieson’s Etymological, please do).

I enjoy words found off the beaten track, away from the likes of scunnered, mingin’, and dreich, which are always trotted out.

They are hardly Scots any more, they swim in many seas.

Slicht (cunning), bourachie (a clique or group), hallirackit (boisterous). Words used to describe those around us.

Words like spaeman let subtle shades of meaning play upon the page. You can see the characters.

Any form of English up and down the land has terms peculiar to it and all are valuable. Brummy, Scouse, Geordie, Glaswegian, Doric, Dundonian words are part of what makes us us.

Words are a way to declare Scots credentials

Unusual colloquial words don’t often appear in newspapers though.

A newspaper should be written in unadorned standard English because its purpose is to communicate.

If you read a news report and don’t understand words in it then the writer has failed in their task.

Opinion pieces, such as this, have more leeway. Your yarn can be spun through a fyning quhele (spinning wheel, used for delicate, fine wool) and a more intricate, challenging piece of work is produced.

An old friend, street poet Gary Robertson, for instance, uses Dundonian admirably in a sharp, clever, and (most importantly) natural way.

But among some writers in some publications, there is a tendency to seed words like doesnae, wasnae, arnae, (doesn’t, wasn’t, aren’t) into otherwise standard English.

This adds very little, especially if, comically, doesn’t and doesnae appear in the same article.

It looks forced. As if the writer is virtue-signalling his or her Scots credentials in the same way that, a generation ago, social climbers pronounced actually as eck-chually.

Plonking phonetic spellings of contractions like wasnae (wasn’t), or determiners like nae (no) into standard English has the opposite effect to what was intended.

It doesn’t make the writer look more Scottish, it makes them sound as if they are trying too hard to be “authentic”.

In a manner of speaking, authenticity is everything

People attempting speeches in Scots, then lapsing into their everyday accent, also always look pitifully false.

This week's #ScottishWordOfTheWeek is Brulzie.

A brulzie is a commotion, a noisy quarrel, an affray.

Pronounced: Bru-lee.#scotsmagazine #scots #scotslanguage #language pic.twitter.com/DI7tTKJwSr

— ScotsMagazine (@ScotsMagazine) December 2, 2022

Speak naturally. Be who you are.

You will come across as someone to be trusted.

This is true of too many pretend-Cockneys on TV, with their pronunciations of wiv, stwengf, and aw-wight. Poseurs from leafy Surrey avenues who want you to think they grew up with the Kray Twins.

If you’re going to write in Scots then more power to your elbow. Go for it. This would be especially apposite if it is the way you habitually speak.

But make sure you write genuinely, unashamedly, and honestly in Scots.

Every word.

Have the courage of your convictions. At least you will sound like a real person.

Conversation