Immigration is as old as the hills. Folk have moved since time immemorial in search of better lives and to escape war and poverty.

And so the current debate over immigration is nothing new either.

Nor is it just a UK issue. EU countries are currently at loggerheads too.

The Czech Republic imposed temporary border controls on Slovakia after a huge year-on-year increase in the numbers entering the country illegally – mainly young men from Syria.

Meanwhile Italy and France have had a diplomatic row over who should take 234 migrants rescued at sea and refused landing in Italy before being allowed to disembark at Toulon. Forty four of them were refused asylum and are to be deported.

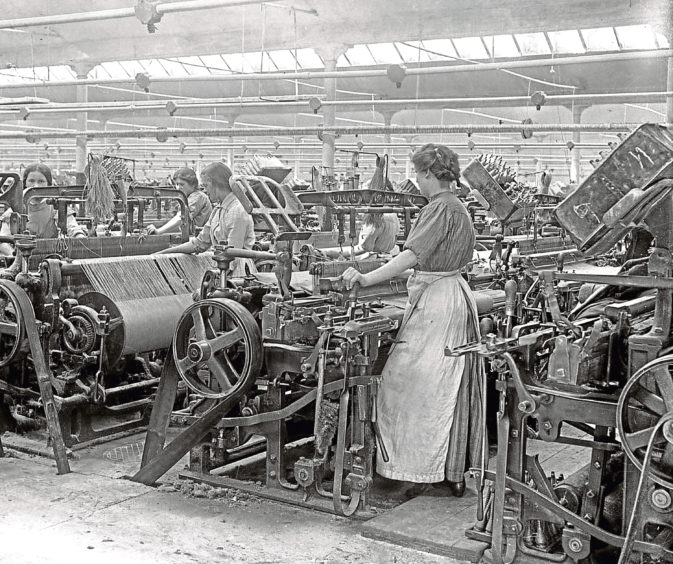

Here in Dundee, immigration helped build the city’s fortunes.

By 1851 the population of Irish-born residents was 18.9%, greater even than Glasgow’s.

Only Liverpool in the UK had more folk hailing from the Emerald Isle.

Lochee was nicknamed Little Tipperary or Tip, because of the huge numbers of folk, the majority of them women, bringing their weaving skills from Ireland to find employment in the jute mills.

And it’s always been a two-way thing.

Scots and Irish have been at the forefront of emigration to America, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand.

Many of us will have friends and relations in those four countries.

UK policy on migrants is a shambles

The current furore over who can come and stay in the UK involves many elements.

And some of them are undoubtedly racist and bigoted.

But that’s no different from over a century ago when some Scots thought the newly arriving Irish were undermining their wages and conditions, leading to riots in some places.

In Dundee we were largely free from the sectarianism accompanying that immigration.

But in some attitudes to modern newcomers, many of the old hostilities are still evident.

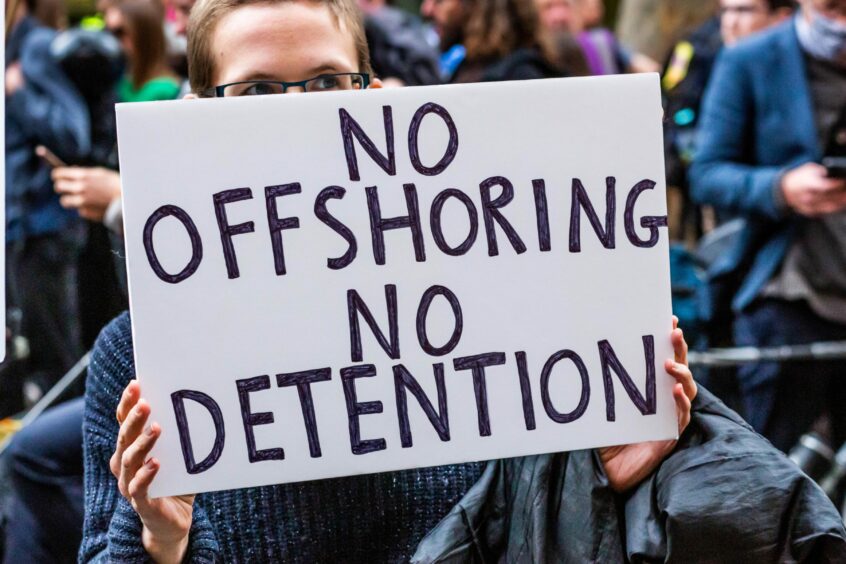

The current asylum system to decide who is fleeing war and danger and can stay, and who is simply looking for a better economic future and must leave, is a shambles.

However, unless you think everyone who wishes to come here should be allowed to remain then some kind of system to decide who can and cannot is needed.

That will inevitably disappoint many hopefuls, but difficult decisions must be made.

The present migrant crisis is so great that it’s even causing some to suggest EU internal Freedom of Movement itself may be threatened unless it can get to grips with the problem.

Problems won’t just disappear

So how should any society cope with concerns over unlimited immigration and the potential stresses and strains on education, housing, and welfare systems?

There’s no proof that the numbers wanting to come to the UK will overwhelm us.

But many people are worried about the possibility of unchecked immigration.

And labelling them all as racists is simplistic. Especially when the accusation is aimed at communities bewildered by the pace of change around them.

The Tories and Labour say they want to stop people smugglers, the serious, organised criminals who are exploiting those dreaming of better lives.

The SNP says: “With independence we can build asylum and immigration systems geared to meet Scotland’s needs and founded on fairness and human rights.”

But what does that woolly statement mean?

Are we looking to adopt a points based system like Australia or an open doors one?

And would it be any more well-managed than the existing UK Government process, which is clearly chaotic and takes far too long to deal with those seeking asylum.

On one side of the debate are those who think we should accommodate permanently all of those who arrive.

On the other, some who are just hard of heart, but also those who know difficult choices are required. And that decisions will dash the hopes and dreams of some asylum seekers.

It’s a dilemma with no easy answers.

But it deserves a mature debate based on facts, not on fear-mongering and falsehoods.

Because this problem isn’t going away anytime soon.