In these times of widespread industrial unrest, the attempts of at least some UK governments of yesteryear to do all they could to settle disputes looks like exactly the right approach, despite criticism at the time and since.

What doesn’t make any sense today is the studied passivity of the current prime minister and his colleagues in the face of mounting strike action.

The transport network, health service, Royal Mail, schools and the civil service are already affected, with the prospect of much more to come in 2023.

The general secretary of the TUC, Paul Nowak, has warned of a “rolling wave” of strikes and unions co-ordinating activity on the same day.

It may not be sufficient in itself, but a necessary ingredient in resolving the situation is government getting involved in Mr Nowak’s call for “serious and sensible discussions about pay”.

Rishi Sunak and his ministerial team may regard their inaction as strategy.

The long-suffering public are more likely to dismiss it as lethargy.

Labour government would be better equipped to handle UK strikes

Inasmuch as there is ideology at play here, what is happening is an attempt by the Conservative administration to return to the right’s political comfort zone: minimalist government.

However, given the extraordinary levels of government intervention needed to deal with the impact of the pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, inflation, and energy price shocks, the days of “laissez-faire” in our public life are past.

And in the past they must remain.

That is one reason why a Labour government is more relevant and suited to the times we are in than any of the many brands of Conservatism.

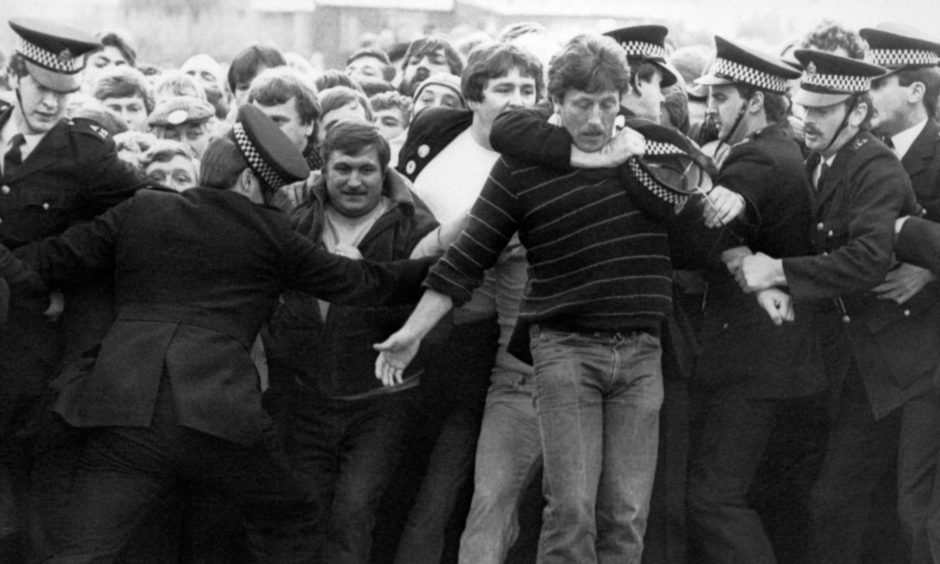

In the battle of ideas, it became important to the governments of Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s to deride the efforts of her Labour predecessors in taking an active approach to industrial negotiations.

The situation in the 1960s and 1970s was further complicated by many of the disputes being unofficial.

The “beer and sandwiches” with union representatives in Downing Street went stale during the winter of discontent.

However, we should not allow the caricature to blind us to the benefits of government involvement.

In Harold Wilson’s account of the 1964-70 Labour administration, the then prime minister describes how ministerial intervention helped to prevent a rail strike in 1966.

Perhaps presciently, Mr Wilson also tried (ultimately unsuccessfully) to lay the “beer and sandwiches” myth to rest.

The reality was a somewhat chaotic effort to gather sustenance at Number 10 on the not unreasonable grounds that “the railwaymen had had hardly any lunch”.

As he wrote: “the facts were funnier than the fiction”.

UK and Scottish governments take contrasting approach to strikes

Whenever there is significant industrial discord, the more serious fiction is that government genuinely has its hands off the situation.

The truth is that ministers pull the strings, financial and otherwise.

To take one example: the report of the Scottish independent review group in 2020 (which paved the way for miners convicted during the 1984-5 strike to be pardoned) noted that UK cabinet minutes provide evidence of, at the very least, “scant regard for the independence of the police”.

Government ought to be part of the solution – not stoking problems.

In Scotland, there continues to be a tradition of proactivity in trying to resolve disputes.

Last September, the bin strike was called off after late-night talks involving the first minister.

Pay negotiations with the RMT union at ScotRail have been settled, though the UK-wide Network Rail strike continues.

In the NHS, Unison and Unite members have accepted a revised Scottish pay offer. But other unions including the Royal College of Nursing have rejected it.

Hopefully, all concerned have made a New Year resolution to keep talking.

Conversation