Many years ago, 1984 to be exact, I remember listening to a radio programme about whether any aspect of George Orwell’s post-war novel of that name, portraying a dystopian future, had come true.

Happily, the answer was no.

Except one of the contributors argued that there was an echo in our society of the contradictory names Orwell gave to the institutions of his imagined superstate of Oceania.

The Ministry of Truth told lies and the Ministry of Love tortured people.

The particular, and happily for us benign, example that he proffered was the NHS.

His point was that we call it a National Health Service, when in reality it is primarily a national sickness service.

Obviously, the NHS in its many manifestations fosters healthy living.

But as this winter is demonstrating all too clearly, it is at the extremely sharp end of dealing with a critical mass of illness – including rising Covid infections, high levels of seasonal flu and cases of Strep A.

To put it mildly, the system is struggling to cope.

Bed occupancy in Scotland has exceeded 95%, and delayed discharge from hospital is chronic.

NHS future won’t be secured by a change of health secretary

The prevention of ill-health is of course part of the overall mission of the NHS (vaccination programmes are an important case in point).

This was institutionalised in the establishment of Public Health Scotland in 2020, which is tasked with working “to prevent disease, prolong healthy life and promote health and wellbeing.”

In reality, the success of preventative action depends on policies delivered across every sphere of government: economic and social, welfare and growth, national and local.

A valid aspect of this wider perspective is what Westminster is doing and what Holyrood can’t do under its current powers.

Ultimately, the health of the nation is about our collective commitment as a society.

That goes beyond health policy in the narrow sense.

And it’s more fundamental even than how much we are willing to invest in the NHS in any given year.

The more we are prepared to tolerate and even accentuate poverty and inequality, the more our health service will have to cope with the scale of sickness – physical and mental – that flows from these social evils.

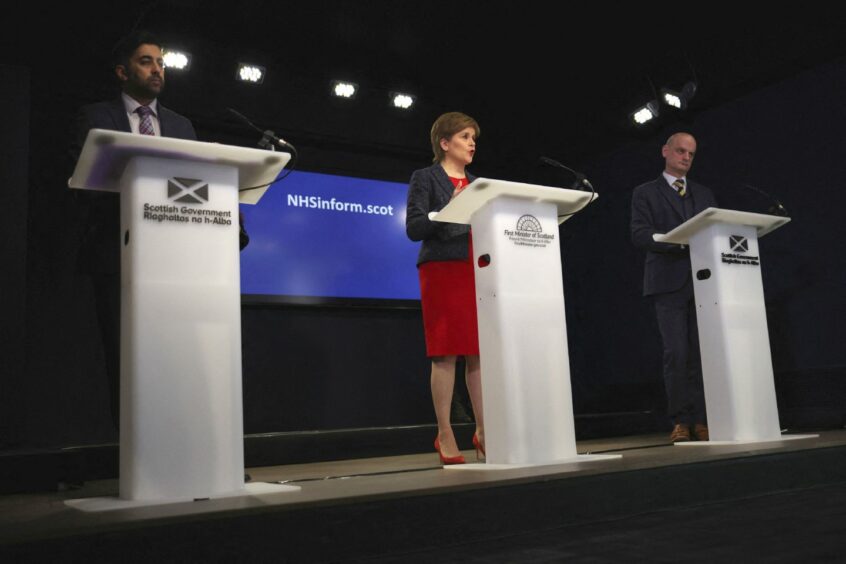

While it is right that the Scottish Government is held accountable for the failings of NHS Scotland, I hope we can use the current crisis to have a much deeper discussion than whether or not Humza Yousaf should continue in post as health secretary.

Humza Yousaf has failed on:

⚠️Delayed discharge.

⚠️Workforce planning.

⚠️A&E waiting times.

Now that the First Minister is doing his job, he should resign. pic.twitter.com/7rJyTxNMZn— Craig Hoy MSP (@CraigWHoy1) January 10, 2023

Removing him at this stage wouldn’t make a jot of difference in improving the situation.

Equally, and more troubling for the opposition parties in the Scottish Parliament, changing the government at Holyrood wouldn’t make things any better either.

Different governments, same struggles – so what now for the NHS?

There is a Conservative government that presides over the NHS in England, a Labour administration in Wales with full responsibility for the health service, and devolved arrangements in Northern Ireland.

Amid this rainbow of political diversity, those in charge are struggling with exactly the same problems, and in varying degrees failing significant numbers of people in need.

An NHS funded by taxes and free at the point of need is the overwhelming choice of people in Scotland and the rest of the UK, and rightly so.

Beyond that, there is an evident case for changing how care is delivered, not least given ongoing medical advances as well as an ageing society.

However, the sheer scale of the NHS may create the phenomenon of quantity being a quality in itself, which can impede reform and efficiency.

Prescriptions will vary, but we should agree that the future of the NHS is too important for superficial political debate.

Conversation