Every so often a movie comes along that really gets you thinking. For me, it’s Todd Field’s Tar.

It’s compelling, thought-provoking and utterly absorbing, not least because of the questions it raises about our times.

While Cate Blanchett gives arguably the most brilliant performance of her career, the clever layers of meaning in Tar throw light on sexual manipulation, abuse of power, women in male-dominated professions and the power of social media.

Power of social media

It’s not the main focus of this clever character study – there are so many layers to this film – but the role of social media is interesting.

The fictitious character Lydia Tar is, when we meet her, one of the most successful classical conductors in the world, at the peak of her career.

She is a potential target for prejudice too. She’s powerful, sometimes ruthlessly so, she’s opinionated, she’s a lesbian. She shares an adopted daughter, a little girl, with her partner, Sharon.

And then, at the height of her success, Lydia is exposed for (probably sexually) exploiting aspirant young female conductors. Not only that, but she seems to heartlessly discard them once she loses interest.

Downfall in free fall

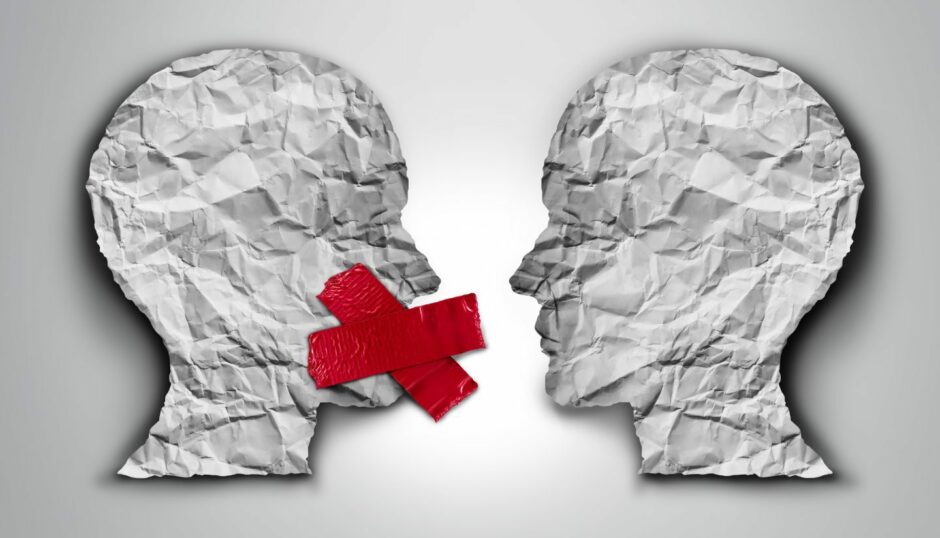

Her downfall goes into free fall and social media rises against her. Then an edited clip of a passionate argument she gave at a Julliard masterclass appears. The edits, out of context, look even more damning in the court of online public opinion.

While the character of Lydia Tar, and the film, merit hours of discussion, the out-take from the Julliard lecture fascinated me.

Essentially, Lydia’s soliloquy was about whether you ‘cancel’ or disregard an artist because you don’t like their lifestyle or apparent belief system, and ignore the greatness of their art (Bach, in this case).

We know how quickly a social media storm can happen. There was a pile-on last weekend, after Dundee’s Transgender rights rally in protest at Westminster’s attempts to block Holyrood’s gender recognition reforms.

Transgender rights rally

Cllr Lynne Short, the long-standing councillor for Maryfield, made a speech in support of transgender rights recognition.

Referencing a trip to Auschwitz, she said “you understand why we have protective characteristics, because some people were experimented on because of disabilities, or because of their sexual preferences, or just because they weren’t the right party.”

Furious online voices called for Cllr Short’s resignation. And her message? About compassion, human rights, tolerance and acceptance? That got lost in the noise.

Cancel culture

And then there’s cancel culture. One of the earliest examples was an American communications executive, Justine Sacco.

She had just 170 followers when she tweeted before take-off on a flight to Cape Town in December 2013.

“Going to Africa,” she tweeted. “Hope I don’t get AIDS. Just kidding. I’m white!” By the time she landed, her life, and career, were in ruins. The content of her Tweet aside, this is power of the court of social media.

Public shaming

In 2015 British journalist Jon Ronson, intrigued by the rise of this new form of public punishment, wrote a book, So You Have Been Publicly Shamed. It’s worth reading, even nearly a decade later.

Before Twitter, state-sanctioned public shaming was phased out by both the United States and the UK in the 19th Century. Today’s social media is uncharted territory.

Public figures face constant online abuse. But money and power seemingly helps shield some from life-destroying consequences.

Trump and Musk

Donald Trump, not known for considered Tweets, is still with us. Elon Musk is also still with us. He faced global outrage in 2018 when he referred to the British diver, one of the rescuers of the 12 boys and their coach trapped in a flooded Thai cave as a “pedo guy”. This after Musk’s offer of a mini-submarine to help with the rescue was rejected.

Now Musk owns Twitter.

A study by Yale University, published last year, showed how social media has profoundly influenced our behaviour online. And let’s face it, that’s where so much of today’s conversations are.

The study found social media’s algorithm encourages us to amplify our outrage online as this makes us more ‘popular’.

We get more ‘likes’ and ‘shares’, code for acceptance and approval. In short, angry words make us friends, admittedly with people we’re unlikely to meet.

Yale researchers studied 12.7 million tweets from more than 7000 users. The conclusion?

Outrage and likes

“Social media’s incentives are changing the tone of our political conversations online,” Yale’s William Brady was quoted as saying. He’s the author of the study and led the research.

They also found a troubling link between social media and political polarisation. Members of more extreme political groups expressed more outrage than moderate thinkers, but moderate thinkers were more likely to be influenced by the social media reward system.

Moral outrage is also a force for much good. But against the social media algorithm of instant reward and punishment, it can also motivate us towards dark, destructive behaviour.

Social media’s influence on our lives is arguably unparalleled. It also leaves us wide open to manipulation. Take the evidence of Russian bots influencing Brexit, and arguably election outcomes. Take Cambridge Analytica.

What if…

Yet, here’s a thought. What if, by raging on social media to harvest likes and ‘friends’, you are helping to distract away from good people trying to do good things, while messages are lost in the shouting?

But, back to Tar, and the scene at Julliard. That it was used as a social media weapon, out of context, was cheap and unfair. Like so many online attacks.

That’s the thing about social media, it blurs the lines between reality and fantasy. Facts often take a back seat.

As for Tar, it’s a film about much more than this. You should see it.

Conversation