At some point – perhaps even some point soon – Nicola Sturgeon is likely to sit down to write her political memoir.

This has been de rigueur for leaders for thousands of years.

Caesar had his Commentaries, Alfred the Great had his Chronicle and so Sturgeon will have her memoir.

Written reflections are a tried and tested way of attempting to secure your place in history and attacking your enemies.

Indeed, as one of Dundee’s more famous representatives would later remark, when questioned in 1948 about Conservative Party foreign policy before World War Two: “It will be found much better by all parties to leave the past to history, especially as I propose to write that history myself” – often paraphrased as, history will be kind to me for I intend to write it.

The desire of political leaders to shape the historical interpretation of their actions was perfected in the last century by President Kennedy and his brother Robert.

The Kennedys decided Camelot – as their administration became known – needed a court chronicler and employed the Pulitzer prize-winning Harvard historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. in the task.

Having witnessed monumental events such as the Cuban Missile Crisis and 1968 election campaign first-hand, Schlesinger produced two superb if naturally favourable histories – A Thousand Days and Robert Kennedy and His Times – that have gone a long way in helping to secure the legacy of the brothers today.

Nicola Sturgeon memoir is unlikely to be a page turner

Sturgeon, of course, does not have a court let alone a historian, and the acute problem facing her will be what to actually write in this tome.

What are her great achievements, her immutable successes?

What does she want to claim as her own and highlight for the future?

She has been electorally successful, of course.

But recounting a series of election victories – often against weak and demoralised opponents – is hardly going to make for a compelling 400-pages.

Equally, she has repeatedly failed to deliver a second referendum, let alone independence, despite constant attempts and allegedly favourable circumstances.

At the same time, her policy achievements are negligible.

Despite nearly a decade in office, and many more at senior levels of government, she has no real legacy to speak of or protect.

Indeed, standards, be it in health or her one-time priority of education, have actually fallen under her stewardship.

Like Boris Johnson, who has apparently already received a £500,000 advance for his memoir, Sturgeon steered the country through Covid-19.

But, again, that process was hardly without fault.

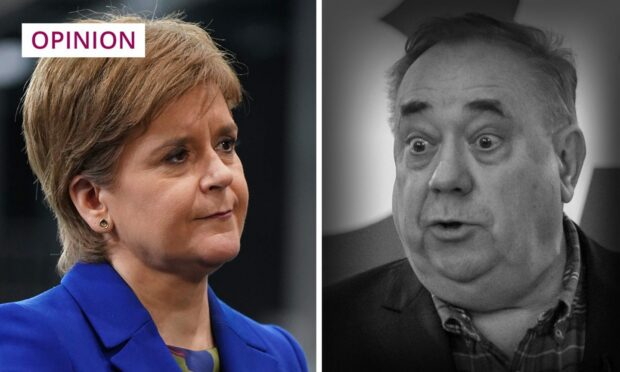

Will Salmond be chief villain of the Nicola Sturgeon memoir?

With few achievements to secure, Sturgeon can always fall back on that other preserve of the political memoir, attacking her enemies.

And the First Minister herself already seems to recognise that this will form the magnum in her opus.

When discussing the prospect of writing a memoir on BBC Radio 4’s PM, she added ominously: “So anybody listening who might feel they have to beware of that, there’s some warning for you.”

Chief in Sturgeon’s sights will be her predecessor, Alex Salmond.

The prospect of further revelations about the collapse of the relationship between master and apprentice will delight journalists and intrigue seasoned political observers.

Any revelations might be somewhat undermined by Sturgeon’s acknowledgement that she has not kept a record of events, but this will matter little.

One need only look at the Duke of Sussex’s Spare to recognise that the red meat of memoires is not objective truth but perspective drama.

Yet, while the promise of such content will help with an advance and sales, it will not help her memoir rank amongst the greats.

Indeed, with few notable achievements other than a monumental falling out with her predecessor, Sturgeon will be left in the unusual position of having history be unkind to her because she intends to write it.

Conversation