We live in strange times in Scottish politics. Some would say it was always thus.

A YouGov opinion poll at the weekend was universally written up as not very good for the SNP, which at one level is fair enough.

Support for the party and independence had both slipped by six points: a hefty dunt.

The reasons aren’t hard to speculate about – a struggling health service, teachers’ strikes, the ongoing controversy over transgender law reform.

The Scottish Government owns all the problems within the devolved sphere.

And symptoms of troubles that track back mainly to Westminster or further afield – such as a faltering economy and cost of living crisis – are generously thrown in the direction of the SNP/Green administration by opposition MSPs.

Therefore, after nearly 16 years in office, surely the SNP must be deep in the doldrums of public esteem?

That is what political theory would suggest.

The reality is quite the opposite.

In the poll, the SNP’s lead for the Scottish Parliament constituency vote was 18 points.

Ordinarily, for a party of government to be so far ahead, it would have to be performing at the top of its game. The political skies would need to be cloudless.

Neither of these conditions apply at present. So what is going on?

Poll results don’t paint whole picture of SNP dominance

Part of the answer is that the Scottish Government is going on.

Many people remain reasonably satisfied, if not ecstatic, with its record and regard it as generally well-intentioned though by no means without flaws and blind spots.

But it has no business being so far out of reach of the opposition parties.

Sixteen years after coming to power in 1979, Margaret Thatcher had long been ousted from Downing Street and the Conservatives were heading for a massive election defeat to Tony Blair.

The same timescale after Mr Blair become prime minister in 1997, he was history and Labour had been ensconced on the opposition benches again for three years and counting.

In other words, a big part of the strangeness of Scottish politics is the malfunctioning of the opposition.

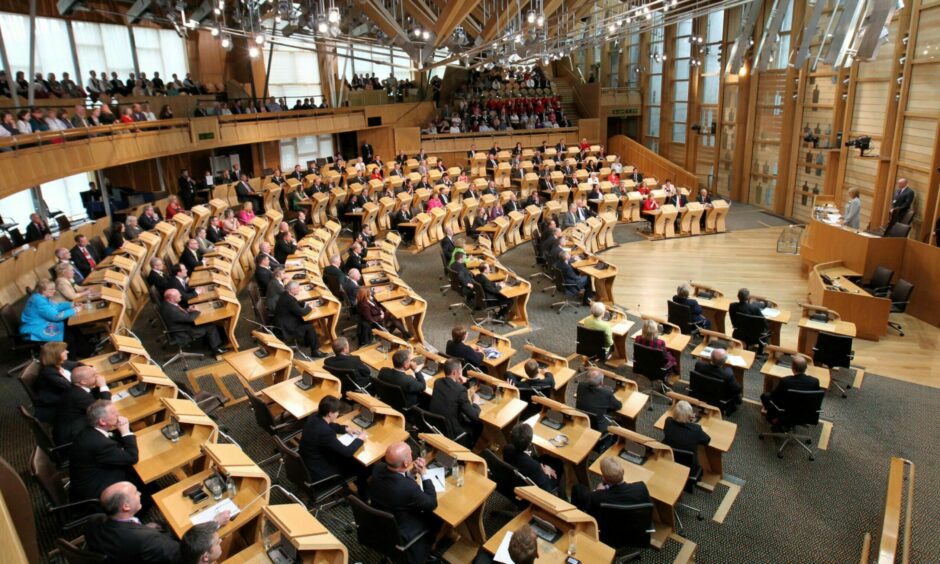

It functions at Holyrood mechanistically but in a political sense ineffectively, at least so far.

There is no pre-eminent opposition party in Scotland, and so there is an element of divide and rule about the SNP’s longevity in government and continued dominance.

Opposition ‘threat’ remains weak

The Scottish Conservatives managed to pull themselves up into second place on a constitutional agenda of opposing another referendum on independence.

However, they are much weaker on social and economic policy (although the transgender row has given them some political purchase), and their popularity is punctured by the Conservatives’ antics at Westminster.

Labour, by contrast, is generally stronger on issues such as public services and the cost of living.

But it has been weak on the constitution in recent years, paralysed in the middle of a polarised debate between the SNP and Tories on an independence referendum.

Labour has leapfrogged the Conservatives in Scottish opinion polls but remains in third place in terms of MSPs.

Also, while Labour’s rising fortunes in England are lifting the party’s boats in Scotland just now, a Labour government at Westminster next year could start to set the process in reverse.

Keir Starmer and his colleagues would become the custodians of all the UK’s travails, causing problems for Scottish Labour.

Among opposition MSPs, only three have any experience of government. Two Labour members were ministers at Holyrood years ago and the Scottish Conservative leader, Douglas Ross, briefly served at the Scotland Office.

The SNP may not have its troubles to seek, but I don’t see these numbers going up anytime soon.

Conversation